The First Step Act was supposed to help free terminally ill and aging federal inmates who pose little or no threat to public safety. But while petitions for compassionate release skyrocketed during the pandemic, judges denied most requests.

By Fred Clasen-Kelly, KFF Health News —

Jimmy Dee Stout was serving time on drug charges when he got grim news early last year.

Doctors told Stout, now 62, the sharp pain and congestion in his chest were caused by stage 4 lung cancer, a terminal condition.

“I’m holding on, but I would like to die at home,” he told the courts in a request last September for compassionate release after serving about half of his nearly 15-year sentence.

A federal compassionate release law allows imprisoned people to be freed early for “extraordinary and compelling reasons,” like terminal illness or old age.

Stout worried, because covid-19 had swept through prisons nationwide, and he feared catching it would speed his death. He was bedridden most days and used a wheelchair because he was unable to walk. But his request — to die surrounded by loved ones, including two daughters he raised as a single father — faced long odds.

More than four years ago, former President Donald Trump signed the First Step Act, a bipartisan bill meant to help free people in federal prisons who are terminally ill or aging and who pose little or no threat to public safety. Supporters predicted the law would save taxpayers money and reverse decades of tough-on-crime policies that drove incarceration rates in the U.S. to among the highest in the world.

But data from the U.S. Sentencing Commission shows judges rejected more than 80% of compassionate release requests filed from October 2019 through September 2022.

Judges made rulings without guidance from the sentencing commission, an independent agency that develops sentencing policies for the courts. The commission was delayed for more than three years because Congress did not confirm Trump’s nominees and President Joe Biden’s appointees were not confirmed until August.

As a result, academic researchers, attorneys, and advocates for prison reform said the law has been applied unevenly across the country.

Later this week, the federal sentencing commission is poised to hold an open meeting in Washington, D.C., to discuss the problem. They’ll be reviewing newly proposed guidelines that include, among other things, a provision that would give consideration to people housed in a correctional facility at risk from an infectious disease or public health emergency.

The situation is alarming because prisons are teeming with aging inmates who suffer from cancer, diabetes, and other conditions, academic researchers said. A 2021 notice from the Federal Register estimates the average cost of care per individual is about $35,000 per year. Incarcerated people with preexisting conditions are especially vulnerable to serious illness or death from covid, said Erica Zunkel, a law professor at the University of Chicago who studies compassionate release.

“Prisons are becoming nursing homes,” Zunkel said. “Who is incarceration serving at that point? Do we want a system that is humane?”

The First Step Act brought fresh attention to compassionate release, which had rarely been used in the decades after it was authorized by Congress in the 1980s.

The new law allowed people in prison to file motions for compassionate release directly with federal courts. Before, only the director of the Federal Bureau of Prisons could petition the court on behalf of a sick prisoner, which rarely happened.

This made federal lockups especially dangerous at the height of the pandemic, academic researchers and reform advocates said.

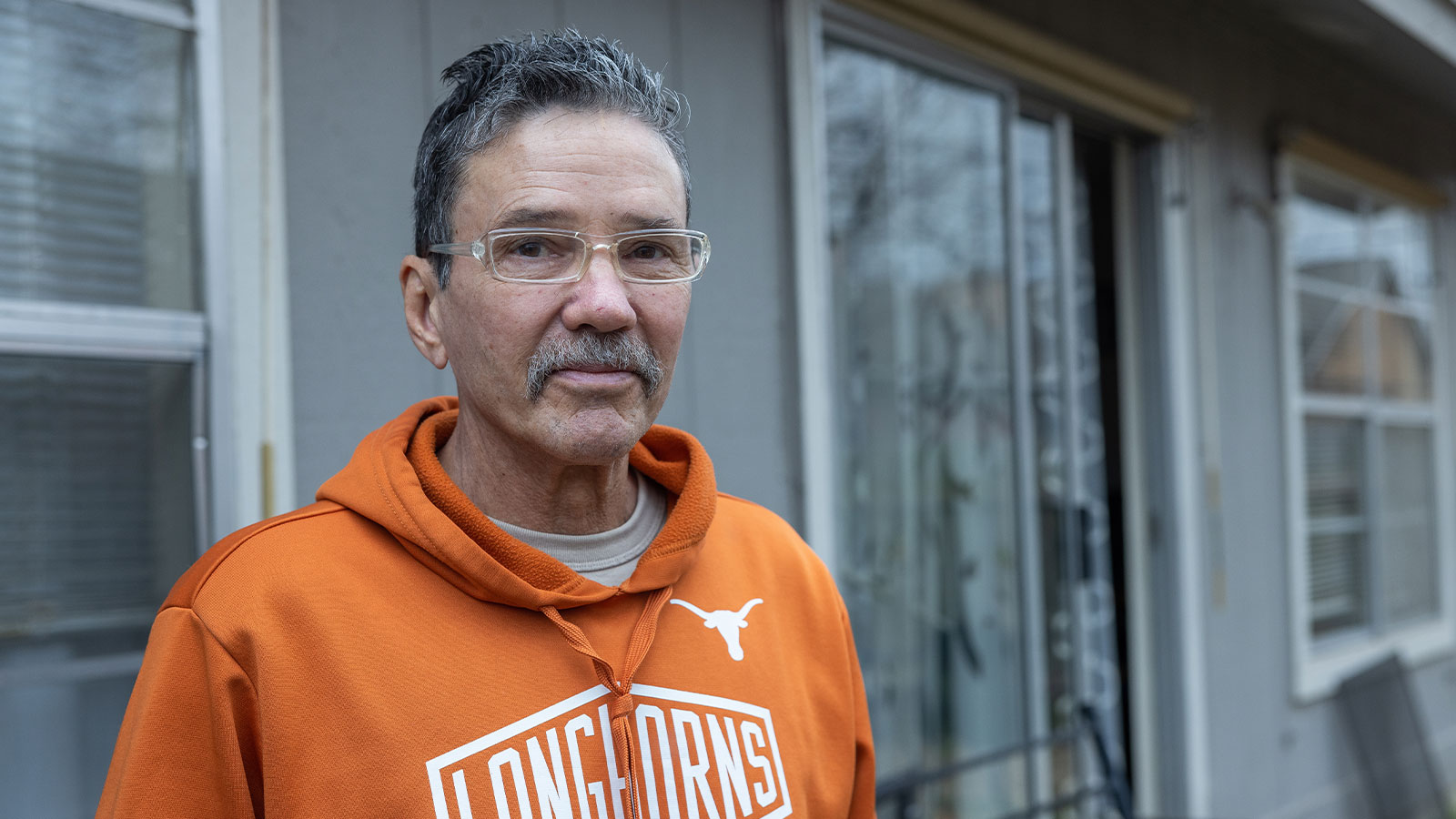

Jimmy Dee Stout outside his brother’s home in Round Rock, Texas. The idea of battling cancer in a prison with high covid-19 rates troubled Stout, whose respiratory system was compromised. “My breathing was horrible,” he said. “If I started to walk, it was like I ran a marathon.”(JULIA ROBINSON FOR KHN)

In a written statement, Bureau of Prisons spokesperson Benjamin O’Cone said the agency placed thousands of people in home confinement during the pandemic. “These actions removed vulnerable inmates from congregate settings where covid spreads easily and quickly and reduced crowding in BOP correctional facilities,” O’Cone said.

The number of applications for compassionate release began soaring in March 2020, when the World Health Organization declared a pandemic emergency. Even as covid devastated prisons, judges repeatedly denied most requests.

Research shows high rates of incarceration in the U.S. accelerated the spread of covid infections. Nearly 2,500 people held in state and federal prisons died of covid from March 2020 through February 2021, according to an August report from the Bureau of Justice Statistics. Charles Breyer, former acting sentencing commission chair, has acknowledged that compassionate releases have been granted inconsistently.

Data suggests decisions in federal courts varied widely by geography. For example, the 2nd Circuit (Connecticut, New York, and Vermont) granted 27% of requests, compared with about 16% nationally. The 5th Circuit (Louisiana, Mississippi, and Texas) approved about 10%.

In the 11th Circuit (Alabama, Florida, and Georgia), judges approved roughly 11% of requests. In one Alabama district, only six of 141 motions were granted, or about 4%, the sentencing commission data shows.

Judges in the 11th Circuit seem to define “extraordinary and compelling reasons” more conservatively than judges in other parts of the nation, said Amy Kimpel, a law professor at the University of Alabama.

“This made it more difficult for us to win,” said Kimpel, who has represented incarcerated people through her role as director of the Criminal Defense Clinic at the university’s School of Law.

Sentencing commission officials did not make leaders available to answer questions about whether a lack of guidance from the panel kept sick and dying people behind bars.

The new sentencing commission chair, Carlton Reeves, said during a public hearing in October that setting new guidelines for compassionate release is a top priority.

Earlier this month, the commission proposed new guidelines for compassionate release, including a provision that would give consideration to people housed in a correctional facility at risk from an infectious disease or public health emergency.

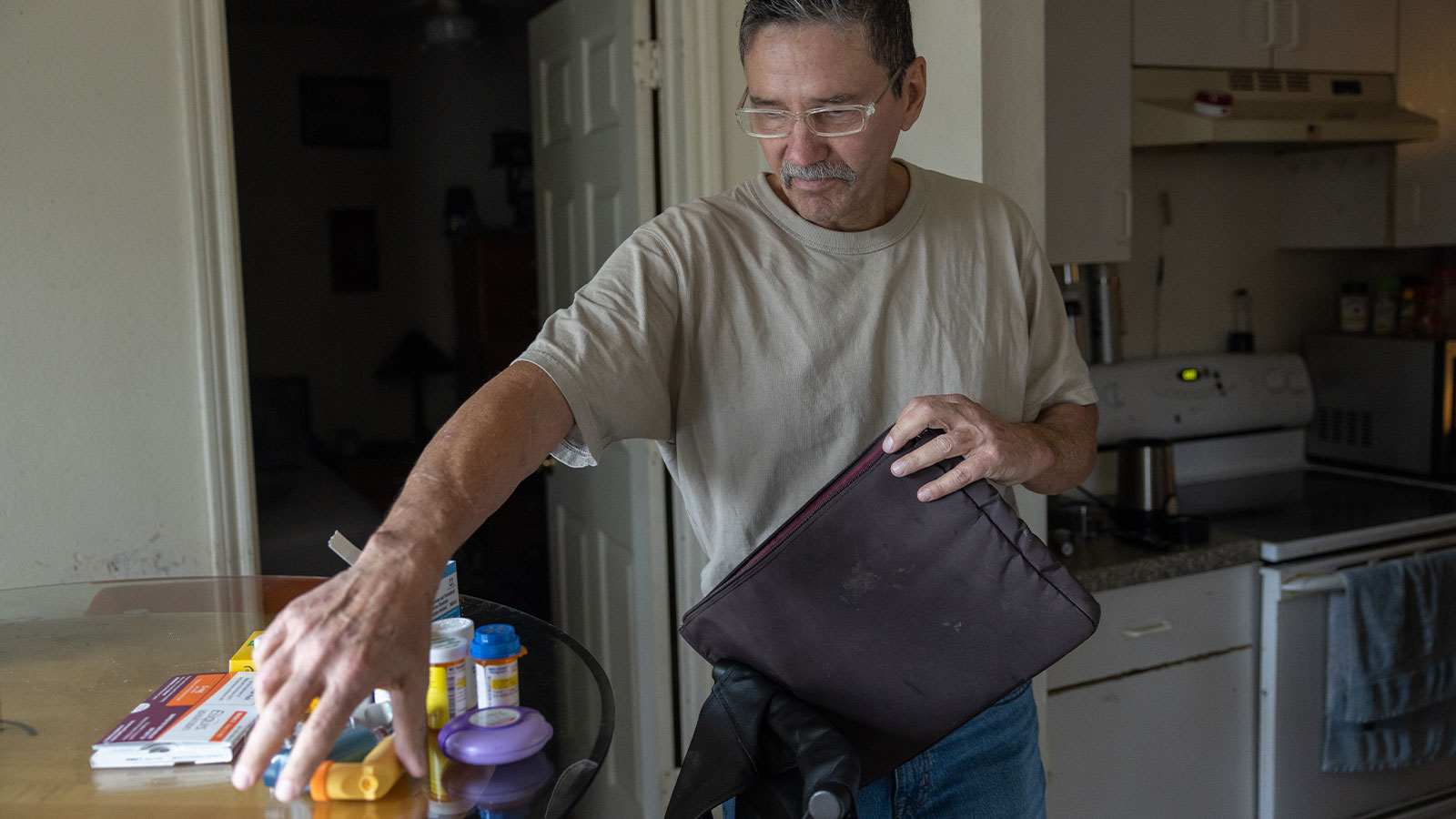

Stout, who has been diagnosed with stage 4 lung cancer, takes dozens of medications to manage his pain and breathing.( JULIA ROBINSON FOR KHN)

Stout said he twice contracted covid in prison before his January 2022 lung cancer diagnosis. Soon after doctors found his cancer, he was sent to the federal correctional complex in Butner, North Carolina.

According to a 2020 lawsuit, hundreds of people locked in the Butner prison were diagnosed with the virus and eight people died in the early months of the pandemic. An attorney for the American Civil Liberties Union, which filed the suit, called the prison “a death trap.”

The idea of battling cancer in a prison with such high covid rates troubled Stout, whose respiratory system was compromised. “My breathing was horrible,” he said. “If I started to walk, it was like I ran a marathon.”

Stout is the kind of person for whom compassionate release laws were created. The federal government has found prisons with the highest percentages of aging inmates spent five times as much on medical care as did those with the lowest.

Stout struggled with drug addiction in the ’80s but said he turned his life around and opened a small business. Then, in 2013, following the death of his father, he drifted into drugs again, according to court records. He sold drugs to support his habit, which is what landed him in prison.

After learning about the possibility of compassionate release from another prisoner, Stout contacted Families Against Mandatory Minimums, an organization that advocates for criminal justice reforms and assists people who are incarcerated.

Then-Chief U.S. District Judge Orlando Garcia ordered a compassionate release for Stout in October.

As Christmas approached, Stout said he felt lucky to be home with family in Texas. He still wondered about what was happening to the people he met behind bars who won’t get the same chance.

Source: KFF Health News

Featured image: Jimmy Dee Stout had served about half of his 15-year sentence for a drug conviction when he was diagnosed with stage 4 lung cancer last year. He learned about compassionate release from another prisoner, and was released last October with help from Families Against Mandatory Minimums. Stout now lives with his brother in Round Rock, Texas. (JULIA ROBINSON FOR KHN)