The school still needs to approve the referendum before it could take effect.

By Beatrice Peterson, Rachel Scott, Erica Y King and Christen Hill, ABC News —

Georgetown University could become the first college in the nation to mandate a fee to benefit descendants of slaves sold by the university nearly 200 years ago — a debate that takes place against the backdrop of a broader political conversation unfolding on the 2020 presidential campaign trail about reparations.

By almost a 2-to-1 margin, students approved the measure, which still must be approved by the university to go into effect.

The school’s undergraduates voted Thursday on the referendum, which would increase tuition by $27.20 per semester to create a fund benefiting descendants of the 272 slaves sold to pay off the Georgetown Jesuits’ debt — a move that saved the university financially.

The results of the referendum are as follows: 66.08% for yes (2541 votes), 33.92% for no (1304 votes). This means that the referendum passes.

— GUSA Elections (@GUSAElections) April 12, 2019

Todd Olson, vice president for student affairs at Georgetown University, in a statement issued after the vote, lauded the students’ efforts saying ” university values the engagement of our students and appreciates that 3,845 students made their voices heard in yesterday’s election. Our students are contributing to an important national conversation and we share their commitment to addressing Georgetown’s history with slavery.”

The university has vowed to “carefully review the results of the referendum, and regardless of the outcome, will remain committed to engaging with students, Descendants, and the broader Georgetown community and addressing its historical relationship to slavery,” Matt Hill, the university’s media relations manager, told ABC News in a statement.

“The Jesuits sold my family and 40 other families so you could be here,” sophomore Melisande Short-Colomb, a Georgetown student, said during a town hall to discuss the issue last week.

She’s one of four students currently attending the university under an admissions policy that considers the descendants of the 272 slaves as “legacy” students.

There is an obligation for Georgetown to reconcile its sins, and that obligation

falls squarely on the institution.

That group also includes Elizabeth Thomas, who will receive her master’s degree from Georgetown University in May and is a desk assistant at ABC News in Washington. She’s a descendant of Sam and Betsy Harris, who were enslaved and sold by Georgetown University in 1838. If the current referendum passes, it’s unclear whether Thomas would receive any reparations in the future.

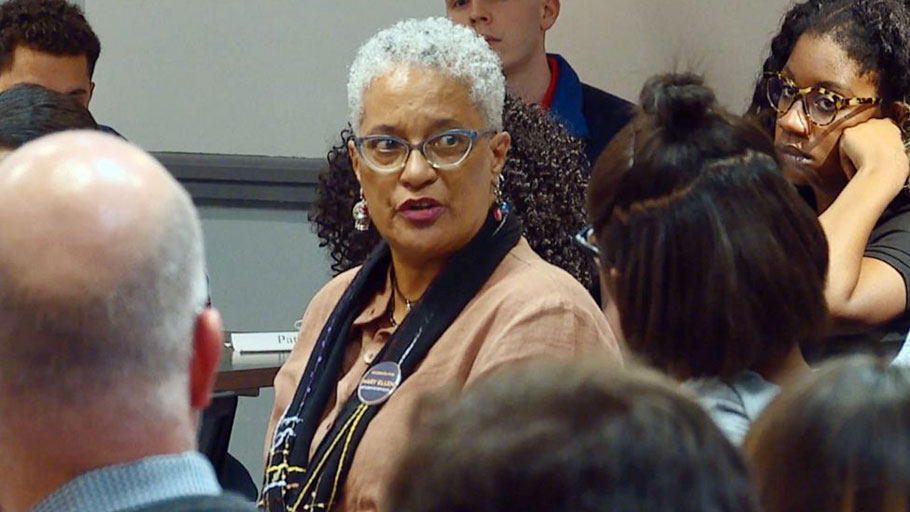

Melisande Short-Colomb, a sophomore and descendant of the 272 slaves sold at Georgetown University speaks at a town hall debate in support of the reparations referendum in Washington, April 3, 2019. (Erica King/ABC News)

A week ahead of the vote, Short-Colomb joined 100 other students packed into Georgetown’s Leavey Hall on campus as the gathering mulled the impact of the proposal.

“No one in this room was here in 1838 when this happened,” Short-Colomb said. Still, she thinks the funds could help make amends for the university’s slave-holding past.

“But we have a chance today to make a difference, so I’m going to pay my $54,” she said, referring to the two semesters before she’d graduate.

… #dobetter #voteYES #GU272 @Students4GU272 @SandraGreenTho2 @arothmanhistory @DrMChatelain @Georgetown pic.twitter.com/TAwYj3PF7G

— Chef Méli (@chef_meli) April 9, 2019

A longstanding political debate

The conversation on the Washington campus reflects a larger discussion as reparations take the stage ahead of the 2020 election. A number of the Democratic presidential candidates have weighed in on the issue of reparations for African American descendants of slaves.

The issue of reparations isn’t new. It’s been contentiously refuted since the end of the Civil War. One of the earliest proposals came more than 150 years ago when a general suggested Confederate-owned land should be confiscated and divided up to provide the family of freed slaves 40 acres and a mule.

Melisande Colomb, 63, is majoring in African American Studies at Georgetown University and is photographed in Washington, DC, Aug. 30, 2017. (Marvin Joseph/The Washington Post/Getty Images, FILE)

NAACP President Derrick Johnson supports a reparations measure, originally introduced by Rep. John Conyers and reintroduced in every Congress since 1989, aimed at creating a commission to “make recommendations concerning any form of apology and compensation to begin the long delayed process of atonement for slavery.”

The NAACP began collectively backing it in 2014. That year, journalist Ta-Nehisi Coates wrote an essay supporting reparations that garnered national attention.

“Here we are in 2019 talking about it again. It is a sore spot for this nation,” Johnson told ABC News. “It is something that we must address, so we can get past this moment in time in a way in which the legacy of slavery, the legacy of segregation, the legacy of institutional racism can once in for all be done away with and we can all prosper as a nation as one whole community.”

Last week, during Rev. Al Sharpton’s annual National Action Network convention, the first major gathering of 2020 for those seeking the support of black voters, a number of presidential hopefuls, including former Texas Rep. Beto O’Rourke and former San Antonio Mayor Julian Castro, directly addressed the issue.

O’Rourke said he’d support H.R. 40, a measure re-introduced this year by Democratic Rep. Sheila Jackson Lee of Texas and which could be a means to study the impact of slavery in a way that is “realistically forceful and effective to help African Americans who never had the issue of wealth that was inherited.”

Hannah Michael is a Georgetown sophomore from Houston, Texas, studying African-American Studies. (Christen Hill/ABC News)

Other candidates supporting some form of reparations include Sen. Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts, New York Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand and South Bend, Indiana, Mayor Pete Buttigieg, who said that as president he’d support a reparations bill, which he sees as an issue of “inter-generational injustice.”

Ideas for what reparations could look like are myriad.

California Sen. Kamala Harris on NPR recently floated the idea of studying the impact of “the effects of generations of discrimination and institutional racism and determine what can be done, in terms of intervention, to correct course.”

Sen. Cory Booker, D-N.J., who spoke at the National Action Network last week, reiterated his support for Rep. Jim Clyburn’s 10/20/30 plan, an effort the South Carolina congressman said aims to help counties that had a poverty level of more 20% for more than three decades. Those communities would then receive at least 10% of federal funds from a specific program.

Booker did not say whether he considered the measure a form of reparations. Clyburn, however, said the measure “absolutely” is.

Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders initially indicated that he would not support a reparations bill in Congress, saying on ABC’s “The View,” “I think that right now, our job is to address the crises facing the American people and our communities, and I think there are better ways to do that than just writing out a check.”

However, at the conference he vowed to support the perennial reparations measure.

“If the House and Senate pass that bill, of course I would sign it,” he said, adding that he thought there needed to be study about reparations.

White-Gravenor Hall of Georgetown University is shown. (Aimin Tang/Getty Images)

Paying for sins of the past

The political discussion over reparations as a matter of policy comes as the university still struggles with its past. After news of Georgetown’s slave sale surfaced, the university apologized. In April 2017, the school rededicated two buildings named after two former Jesuit University presidents who facilitated the sale.

Not all students are on board with the proposed tuition increase. Some who oppose it expressed concerns as to where the money would be spent and how long they’d on the hook for paying. Several students noted they were working to support themselves and any additional costs wouldn’t be welcomed.

Others complained the referendum wasn’t comprehensive enough.

Still, others felt it’s not the responsibility of the current generation to pay for sins of the past — a stance that’s come up in previous political debates.

“It’s unjust to compel 7,000-plus people to pay for the university’s historical sins,” said Haley Grande, a sophomore in student leadership at the university. “There is an obligation for Georgetown to reconcile its sins, and that obligation falls squarely on the institution.”

In a statement obtained early Friday by ABC News, Todd Olson, vice president of student affairs at Georgetown, said, in part:

“The university values the engagement of our students and appreciates that 3,845 students made their voices heard in yesterday’s election. Our students are contributing to an important national conversation and we share their commitment to addressing Georgetown’s history with slavery.

“We understand that the goals of the student referendum are to honor the 272 enslaved individuals sold by the Maryland Jesuits in 1838 and to advance ’causes and proposals that directly benefit descendants still residing in underprivileged communities.'”

ABC News’ Justin Gomez and Armando Garcia contributed to this report.