By Jennifer Larino, The Times Picayune —

What can we do to break New Orleans and its neighborhoods free from a long history of racist housing policies?

That’s the question posed by “Undesign the Redline,” a traveling exhibit currently stopped at Tulane University’s Albert and Tina Small Center for Collaborative Design in Central City. A localized version of the exhibit was created by Designing the WE, a New York design firm focused on social impact, in partnership with Enterprise Community Partners, an affordable housing nonprofit.

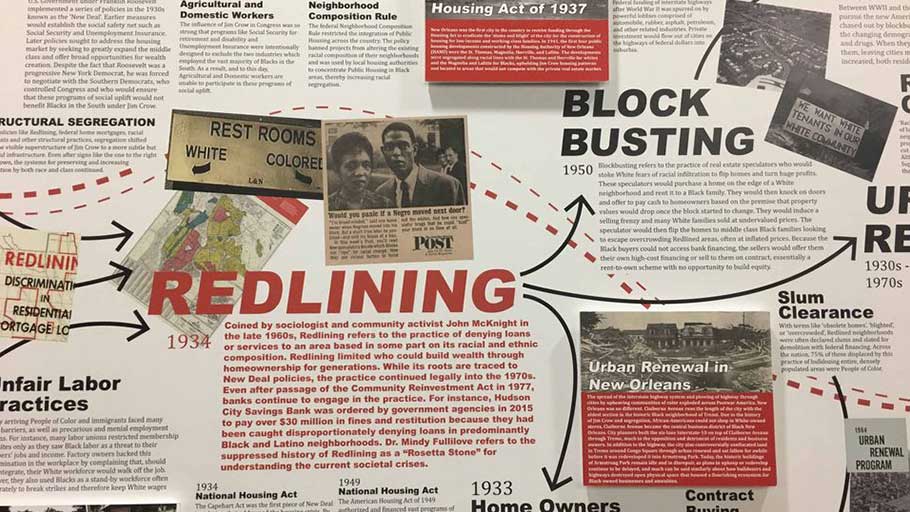

On view through March 1, it looks at the history of New Orleans and the United States within the context of housing policies and practices, from redlining to block busting, that reinforced racial segregation and shaped the neighborhoods we know today.

John Sullivan, senior program director for Enterprise Community Partners on the Gulf Coast, said many people see struggling, impoverished neighborhoods as the result of bad decisions made by the people who live there. A closer look reveals the destiny of many of the country’s roughest neighborhoods was written decades ago, he said.

“We need to see these things as a result of a system, of actions taken over decades that have restricted choice and opportunity,” Sullivan said.

“Undesign the Redline” arrives as New Orleans weighs the future of the city’s housing mix on multiple fronts.

Concern over gentrification in many of the city’s historically poor or working-class black neighborhoods is widespread. The New Orleans City Council voted Thursday (Jan. 10) to approve hotly debated new rules for short-term rentals, including a ban on all rentals in the Garden District and French Quarter. Affordable housing advocates blame for driving lower-income locals out of the city’s urban core.

In coming weeks, the council could also vote on new policy that would, among other changes, increase the number of affordable units that have to be included in new and renovated housing developments. A vote is likely to come after Mayor LaToya Cantrell’s office studies an aspect of the proposal that would make the affordable housing quota mandatory in specific areas where affordability is major concern. That study is due in February.

There is also a renewed push to recognize the role racism has played in local housing. An April 2018 report by The Data Center, part of a series released as the city marked 300 years since its founding, traced how New Orleans housing policy has been marked by discrimination and segregation for more than a century. The report called on the city to make laws to ensure market rate housing is built — much like what the city council is considering now — and to boost investment in fresh food retail, public transit and greenways near affordable housing developments.

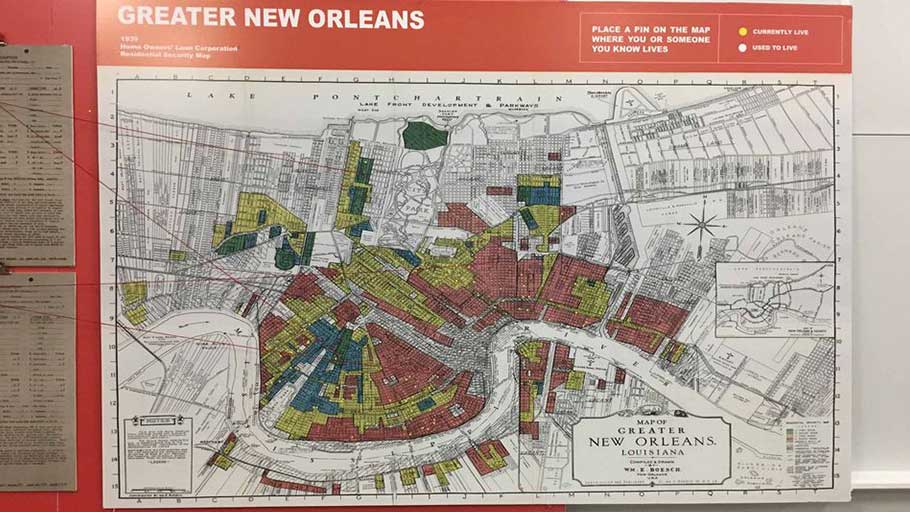

On a recent afternoon, large exhibit panels with photos, maps and text lined the walls of the the front rooms of the Small Center on Baronne Street. Sullivan stopped in front of one of the exhibit’s more striking displays: a large reprint of a Home Owners’ Loan Corp. map from 1939 showing New Orleans neighborhoods overlaid with blocks of green, blue, yellow and red.

As its name implies, much of the exhibit walks viewers through a practice called redlining, which dates back to 1934 when the newly created Federal Housing Administration was working to promote homeownership across the country under President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal. Federal loan agents used color coded maps to determine which neighborhoods were worth investing in. Green areas were considered safest, while red indicated the riskiest bets.

“Undesign the Redline,” an exhibit the history of redlining and other discriminatory housing policies in New Orleans and nationwide, is on view at Tulane University’s Albert and Tina Small Center for Collaborative Design through March 1, 2019. (Photo by Jennifer Larino, NOLA.com, The Times-Picayune)

Redlined neighborhoods were nearly exclusively black or mixed race. Federal loan agents were trained to look for signs of “infiltration of inharmonious racial or nationality groups” when determining whether the government should originate mortgages in a particular area, according to underwriting materials from the time. On the 1939 map, nearly all of New Orleans is red or yellow, with a few splashes of green in present-day Fountainebleau and Lakeview.

The map is a gateway into policies that had “major implications for the ways in which we not only chose to build out our cities, but in terms of who was invited and welcome into them,” said Shana M. griffin, a feminist activist and co-founder of the Jane Place Sustainability Initiative who was on the exhibit’s advisory board.

Visitors can use a push pin to mark where they currently live on the HOLC map and leave notes describing what their blocks look like today. Many of the blocks marked questionable in 1939 are now some of the most expensive areas of the city to live, griffin observed. Also on display are copies of New Orleans neighborhood description forms from the 1930s that describe “negro infiltration,” the term loan agents used when African-American families moved into predominantly white neighborhoods.

Sullivan noted homeownership is the primary way most American families generate wealth. Nearly all families need a mortgage to buy a home. Reading about policies from the early days of the FHA help show how Americans haven’t been on a level playing field when it comes to accessing that wealth, he said.

The result, griffin added, are “generational forms of discrimination” that continue to fuel a widening wealth gap between white families and families of color in New Orleans and in cities nationwide.

The exhibit isn’t limited to redlining. It also provides a timeline of U.S. housing policies from specific eras alongside key historical events. The timeline extends from pre-Civil War to the Jim Crow-era, on through Hurricane Katrina in 2005 to present day. Dedicated placards give a history of segregation and housing battles specific to New Orleans, including the draining of New Orleans-area swampland for housing development, which created suburbs and led to the flight of white families from the city’s core; the fight over Lincoln Beach in New Orleans East; the Road Home program; and short-term rentals.

Sullivan noted the exhibit focuses on history and context, and touches only briefly on the current debate over potential housing solutions. A table stacked with informational pamphlets included a short explainer on the city’s “Smart Housing Mix” study, completed in 2017, which is informing the policies the council is currently considering. Visitors are encouraged to write down their impressions of the exhibit. The intent is to get people thinking about what they can do to change the status quo, Sullivan said.

“What we want people to think about is what will the next panel on that wall look like?” he said, gesturing to the timeline.

For her part, griffin hopes visitors leave the exhibit reflective, but not without hope. There is “amazing work” being done to unwind the grip past policies have had on local housing, she said.

“What was done can be undone,” she said.

“Undesign the Redline” will be on display at the Albert and Tina Small Center for Collaborative Design, 1725 Baronne St., through March 1.

Credit: Article and photos by Jennifer Larino, NOLA.com, The Times-Picayune

Jennifer Larino covers residential real estate, retail and consumer news, travel and cruises, weather and other aspects of life in New Orleans for NOLA.com | The Times-Picayune. Reach her at jlarino@nola.com or 504-239-1424. Follow her on Twitter @jenlarino.