The legacy of slavery — and the centuries of theft it entails — does not dwell in the long-forgotten past for Black people. It’s our now.

By Michelle Singletary, Washington Post —

Dear Reader,

Some of my happiest moments were nursing my three children. As I looked down at their faces, their fingers tangled in my hair, I felt enormous peace and joy.

I never took nursing my babies for granted, because of one story my grandmother told me about her enslaved great-grandmother, Leah Drumwright. Even her last name belonged to the plantation owner.

Leah, who was caring for her own infant, was forced to nurse the baby of the White woman who owned her. And there was one strict rule.

She could nurse her Black baby only on her right breast. Leah’s left breast was reserved for the White baby. The reason she was given was that the left breast is closer to the heart, making the milk healthier, and the best milk had to be given to the White infant.

One evening, overwhelmed from exhaustion after cleaning and cooking for the plantation owners, Leah was caught in the kitchen feeding her own Black child on her own left breast.

Seized with the power of privilege fueled by rage, the White mother smacked Leah hard across the face. She followed the slap with a “whipping,” according to my grandmother.

This story of the beating Leah endured that day has been passed down through the generations of my family. It’s still very real and raw for me as another example of the indignities and brutality experienced by millions of Black people, and not just during the 246 years they were enslaved in America.

But this isn’t a story about Leah’s left breast. It’s about theft.

It’s about the legal systems in America that permitted robbing Blacks, literally to the extent of stealing a mother’s milk from her baby — and that can’t be fully undone unless the thievery is redressed.

“Blacks have been beaten and killed because of their race, denied the right to vote and prohibited from living in certain neighborhoods. They were and still are discriminated against in the workplace and prevented from earning fair and equal pay.”

The institution that empowered that White woman to segregate Leah’s breasts also seeded discriminatory policies that blocked Blacks from building wealth. The centuries of injustice, dear reader, should be reason enough to make a case for reparations.

My family tree harbors another crime. Except on rare occasions, children conceived through the rape of enslaved women didn’t benefit from the wealth of their White fathers. These White men never paid child support for the Black children they fathered. They were the ultimate deadbeat dads.

Black people have been systematically robbed. They have been denied the right to their own bodies; separated from their siblings, spouses and children; and forced to work for free. After the Civil War, many purchased land, only to see it stolen. Prosperous Black towns were looted and burned. Blacks have been beaten and killed because of their race, denied the right to vote and prohibited from living in certain neighborhoods. They were and still are discriminated against in the workplace and prevented from earning fair and equal pay.

“An unsegregated America might see poverty, and all its effects, spread across the country with no particular bias toward skin color,” author Ta-Nehisi Coates wrote in “The Case for Reparations,” a landmark 2014 article for the Atlantic. “Instead, the concentration of poverty has been paired with a concentration of melanin. The resulting conflagration has been devastating.”

Many people contend that reparations to the descendants of Blacks enslaved in America shouldn’t entail millions of individual checks but investment in community institutions or restitution by companies that benefited from slavery.

A new book on reparations recommends a number of possible compensation programs, including the establishment of a trust fund that could make grants to eligible Blacks to help start a business or buy a home.

“While it makes complete sense to seek recompense from clearly identified perpetrators … the invoice for reparations must go to the nation’s government. The U.S. government, as the federal authority, bears responsibility for sanctioning, maintaining, and enabling slavery, legal segregation, and continued racial inequality,” William A. Darity Jr. and A. Kirsten Mullen write in “From Here to Equality: Reparations for Black Americans in the Twenty-First Century.”

Darity is a researcher, economist and professor of public policy and African American studies at Duke University. Mullen, who is married to Darity, is a writer and lecturer who focuses on race and politics.

Darity and Mullen revisit the broken promise of 40 acres of land for each freed Black family in the South after the Civil War. On orders from President Abraham Lincoln, Union Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman in 1865 issued Special Field Order No. 15, authorizing the redistribution of land confiscated or abandoned by Confederates, including miles of coastline along South Carolina, Georgia and Florida.

“Americans bristle at paying reparations to Blacks. Individuals become defensive, arguing, ‘I didn’t enslave anyone.’ … Your ancestors may not have enslaved anyone, but America benefited from the institution of slavery.”

It’s important to point out that the concept of land distribution came from Black ministers who were advising Sherman on a remedy for the atrocities of slavery. They had the right idea, which was to work with the federal government to create a path to economic stability and self-sufficiency for Blacks.

After Lincoln’s assassination, President Andrew Johnson, a Southern enslaver, nullified Sherman’s order.

“Had that promise been kept — had ex-slaves been given a substantial endowment in southern real estate — it is likely that there would be no need for reparations to be under consideration now,” Darity and Mullen write.

Equality in America needs to follow a policy of “ARC,” the authors argue: acknowledgment, redress and closure.

Acknowledgment is a work in progress. A Washington Post-SSRS poll last year found that two-thirds of Americans, 67 percent, say the legacy of slavery still affects society.

But that is where things stall. Only 29 percent of Americans approved of cash payments to the descendants of enslaved people, according to a 2019 Gallup poll.

Americans bristle at paying reparations to Blacks. Individuals become defensive, arguing, “I didn’t enslave anyone.”

“The case we are making isn’t about individual guilt,” Darity said in an interview. “It’s about national responsibility. And historically, this has involved direct payment to the victimized community.”

Your ancestors may not have enslaved anyone, but America benefited from the institution of slavery. Segregation and voter suppression gave advantages to White Americans in the form of cheap Black labor, reduced employment competition and the power to elect politicians who enacted laws that worked in the best interest of Whites and against equal opportunities for Black people.

“The reach of slavery was far from contained in the American South, and the economic effects of slavery were far from limited to the South,” Darity and Mullen write. “The destruction of African families and clans was a key element in the wealth equation for America. Black lives were the price paid to lay the foundation upon which the nation was built.”

Redress is part of the American justice system. People sue for correction and also for pain and suffering. After decades of national denial, the federal government issued an apology and cash payments to Japanese Americans held in internment camps during World War II.

You keep insisting that slavery was too long ago to deserve reparations. But it’s not that long ago if you think in terms of generations rather than years, Darity said.

My own lineage illustrates that point. Leah Drumwright’s son, Byrd Drumwright, my grandmother’s grandfather, was born into slavery. Byrd’s son, Tobie, lived under the brutality of Jim Crow. Tobie’s daughter, my grandmother, was marginalized by segregation laws. My mother was already a mother by the time the Civil Rights Act was passed. I was born just three years before the Voting Rights Act. Even now, with the Nov. 3 election, voter suppression measures are undermining this fundamental right. Despite my success, I’ve experienced racism. My children have also encountered racism.

So, no, the legacy of slavery does not dwell in the long-forgotten past for Black people. It’s our now.

You may see reparations as an unearned handout. But put yourself in that kitchen, being beaten for breastfeeding your own child. Consider the generations of Blacks who have been victimized and terrorized by systemic racism. Reparations are about seeking justice for that which was stolen.

And that makes reparations the most logical, most American, way of recompense.

Sincerely,

Michelle

Source: The Washington Post

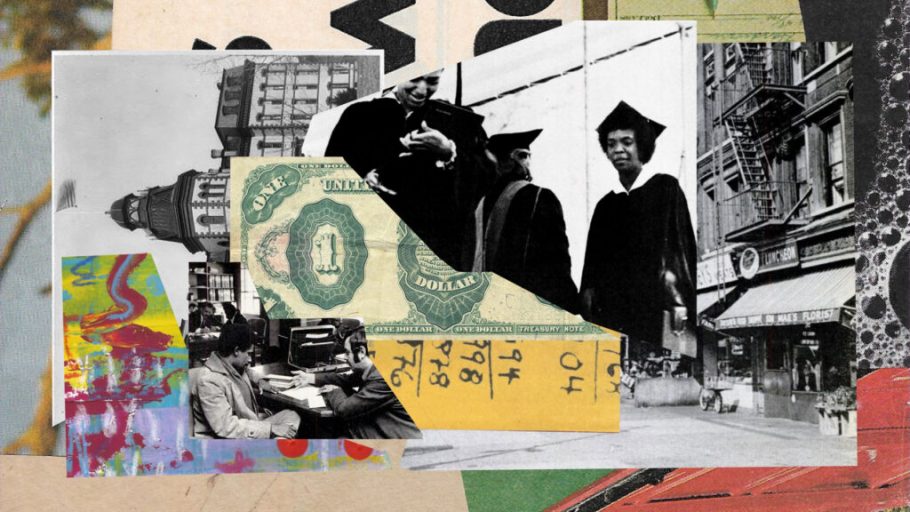

Featured image by Aaron Marin