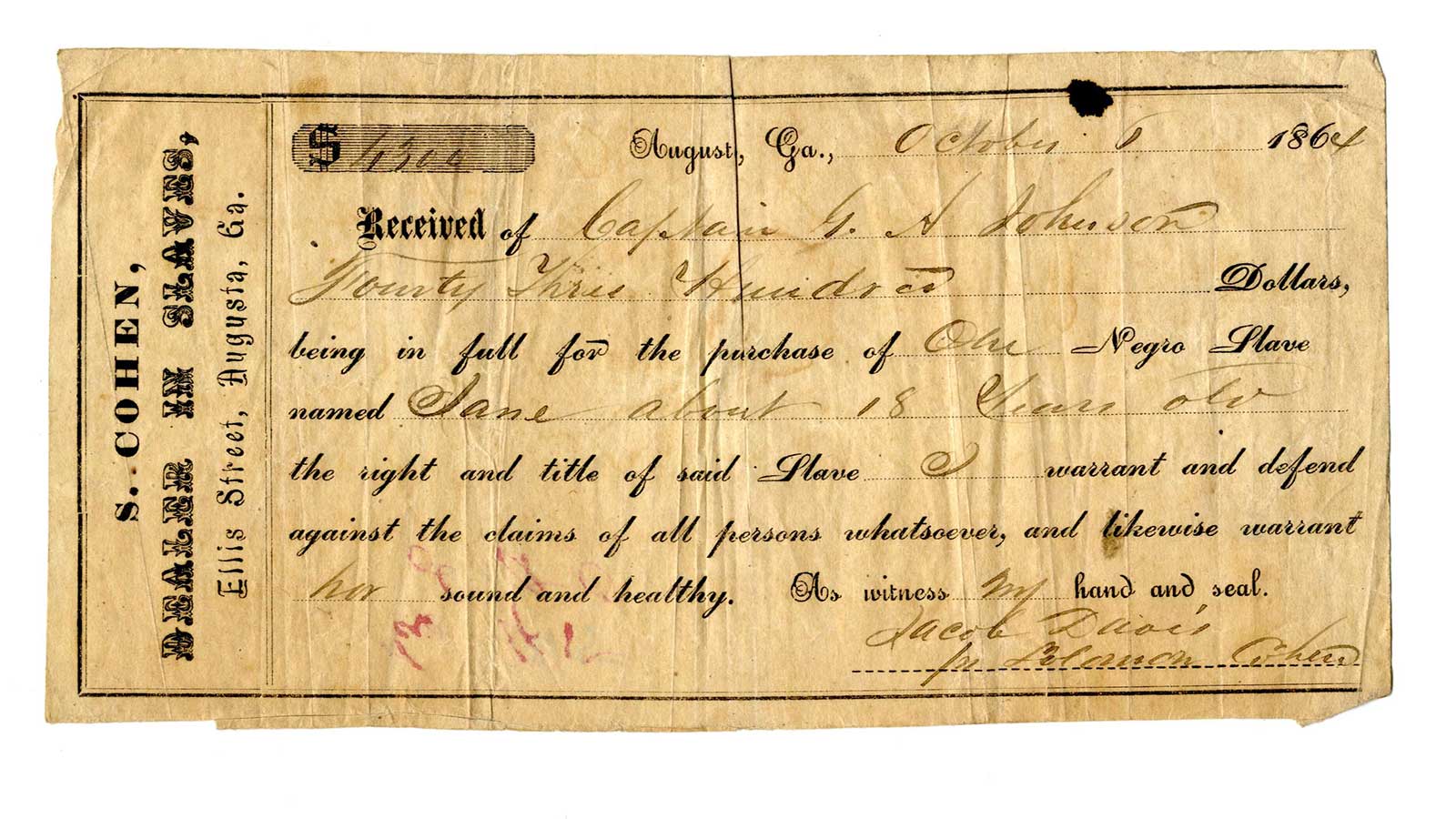

The receipt for the sale of a 9-year-old girl. That, and Derek Chauvin’s knee on George Floyd’s neck for nine minutes, got my attention.

Until these two events, I wasn’t sure what reparations had to do with me, a white woman who has always lived in the American West and who has abhorred the idea of slavery for as long as I’ve known about it.

I wasn’t entirely surprised to learn California has a reparations committee — this state often leads on taking up difficult issues. Many of the millions of Blacks who left the South for a better life came to California, where there were no Jim Crow laws constraining every aspect of their daily lives but where Black people weren’t welcomed into the neighborhood. Redlining, a practice to deny housing to people based on race, took place. In my lifetime, discrimination continues.

Gov. Gavin Newsom has appointed nine Californians of different professions, experiences and racial backgrounds to study how our state might make amends to those who have been wronged. If we are a government of, by and for the people, as our Constitution says, then we each bear some part of the collective responsibility for the injustices perpetrated by any government of which we are a part.

In my case, it’s a personal responsibility. While doing research on my ancestry, I became acquainted with another woman who showed me the receipt signed by one of my ancestors for the sale of a 9-year-old girl. That hit me in the pit of my stomach.

Most who have written about reparations suggest three groups who should pay: state and federal governments that enforced slavery; private businesses that benefited; rich families who acquired much of their wealth from slavery.

But white people — and not just the rich ones — have been accumulating wealth all these years and passing it on to the next generations. I can hear my brother now, saying, “What do you mean by ‘wealth passed down’? Have you forgotten our childhood? A house with no central heat, an outhouse, the years we did row crop work such as detasseling corn so we would have school clothes?’”

He’s right, of course. We were poor white people.

But our parents owned a home. They were never told they couldn’t buy property in certain areas. The institutions and the community were there for us to go to work and to school without anyone looking down on us for our skin color or making laws about where we could live, walk, sit or stand.

As a result of what the community offered, and what we did with it, my sister and brothers and I moved into the middle class and never have wanted for the necessities of life as adults.

We never thought of “white privilege.”

Few Black people lived in Idaho, where I grew up. History lessons taught us about the Civil War, but nothing of the promises made but not delivered, so that generations after that war 6 million Black Americans left the South because they weren’t much better off than during slavery. White people were seen as superior in the eyes of the law.

Many of these laws continued until the Civil Rights Act of 1964. By this time, racism had been practiced so long, it was in the country’s DNA. Most white people fell into it easily. It was the way things had always been.

What would California’s reparations look like? Over the next two years, the committee will ponder that question and make recommendations. Perhaps direct payments, or programs that would pay for education, medical needs and/or housing.

The issue for me might be persuading my family members that reparations are something that could or should be done. Thousands of people, however, have descended from the family who sold the girl. What is our family’s responsibility? Is it a moral obligation?

As I wondered if any individuals were trying to make amends, I was referred to the Beyond Kin Project. It seeks to “encourage and facilitate the documentation of enslaved populations, particularly by recruiting the resources and efforts of the descendants of slaveholders.”

I hope wider conversations about race and our collective responsibilities to right historical wrongs are beginning to take place. They need to — it’s time for a change.

Source: Desert Sun

Featured Image: A receipt for the purchase of an 18-year-old enslaved woman named Jane for $4,300. The document was captured from a Confederate ship during the Civil War. (National Archives)

Lois Requist, a poet and writer, has worked with nonprofits and was on the state board of the League of Women Voters of California, loquuu@gmail.com.