CHICAGO — The nation’s first government reparations program for African Americans was approved Monday night in the Chicago suburb of Evanston, action that advocates say represents a critical step in rectifying wrongs caused by slavery, segregation and housing discrimination and in pushing forward on similar compensation efforts across the country.“Right now the whole world is looking at Evanston, Illinois. This is a moment like none other that we’ve ever seen, and it’s a good moment,” said Ron Daniels, president of the National African American Reparations Commission, which wants redress at local and federal levels.

The Evanston City Council approved the first phase of reparations to acknowledge the harm caused by discriminatory housing policies, practices and inaction going back more than a century. The 8-1 vote will make $400,000 available in $25,000 homeownership and improvement grants, as well as in mortgage assistance for Black residents who can show they are direct descendants of individuals who lived in the city between 1919 and 1969.

The housing money is part of a larger $10 million package approved for continued reparations initiatives, which will be funded by income from annual cannabis taxes over the next decade. Blacks make up about 16 percent of Evanston’s population of 75,000.

More than 60 people spoke before the vote, many endorsing the resolution and calling for the city to take the historic step, others criticizing it and pleading for more time to reshape the plan. Housing assistance, detractors said, isn’t a credible form of reparations.

“It’s a first tangible step,” stressed Alderwoman Robin Rue Simmons, who represents the largely African American Fifth Ward and has been a prime force on the program. “It is alone not enough. It is not full repair alone in this one initiative. But we all know that the road to repair injustice in the black community will be a generation of work … I’m excited to know more voices will come to the process.”

The issue of reparations has been raised nationally for decades, with supporters focusing not just on financial restitution for the descendants of enslaved Americans but on governments’ formal apologies for their role in that legacy.

In the wake of anti-racism demonstrations that swept the country last summer — after the police-involved killings of George Floyd in Minneapolis and Breonna Taylor in Louisville — California established a task force to propose a model for reparations. Chicago and several other cities are discussing reparations programs of their own.

Historian Jennifer Oast, an expert on institutional slavery at Bloomsburg University in Pennsylvania, expects that the Evanston program in particular will have a “snowball effect” on proposed federal legislation.

That measure, H.R. 40, would create a national commission to study potential reparations. It was introduced in 2019 but largely languished until last year’s presidential race when two key candidates, Kamala D. Harris and Joe Biden, voiced support.

A House Judiciary subcommittee held a hearing on the bill last month. The bill has 173 sponsors in the House, but Daniels projects that number “going toward 190,” which makes it likely to pass. It faces a much bigger challenge in the Senate.

While White House press secretary Jen Psaki has not said whether President Biden would sign the legislation into law, but she noted in late February that “he continues to demonstrate his commitment to take comprehensive action to address systemic racism that persists today, and obviously having that study is part of that.”

Robin Rue Simmons, who represents Evanston’s historic Fifth Ward, has been a leading advocate of the city’s reparations initiative. (Kamil Krzaczynski/AFP/Getty Images)

Federal reparations are advocates’ ultimate goal because of the greater monetary resources that would become available. Yet local reparations are important because cities such as Evanston can “serve as a blueprint,” according to Daniels.

Other reparation programs have been created for specific injustices: In 2016, for example, Chicago passed a law to allocate $5.5 million for 57 torture victims of a police unit led by a disgraced former commander. And just last week, the Jesuit order of Catholic priests announced that it would raise $100 million for 5,000 living descendants of enslaved people it owned two centuries ago.

Figuring out how to build reparation programs that address redlining and segregation from the past century is much different than those designed to bring redress for the slave trade, Oast said — primarily because individuals from the Jim Crow and civil rights era are still alive and can directly benefit.

And Evanston should be considered the prototype because of how the city approached its initiative, said Kamm Howard of the National Coalition of Blacks for Reparations in America. “Most other commissions file resolutions and then allocate funds for them, but Evanston set aside the resources up front,” he said.

City leaders decided to first address housing following a report last year that showed how, starting with the arrival of the first Black resident in 1855, Evanston restricted where Blacks could live.

“Over the decades, policies, practices, and patterns of discrimination and segregation took place,” the report said. Together, they “not only impacted the daily lives and well-being of thousands of Evanston residents, but they also had a material effect on occupations, education, wealth, and property.”

Their impact over generations, the report concluded, “was cumulative and permanent. They were the means by which legacies were limited and denied.”

The housing discrimination extended to Evanston’s most famous community: Northwestern University. According to the report, the City Council supported the university’s refusal following World War II to provide housing for Black students, including returning Black veterans.

Despite the city passing a fair housing law in 1968, evidence showed that as late as 1985, real estate agents continued to steer Black renters and home buyers to a section of town where they were the majority. The vestiges of racial segregation remain evident.

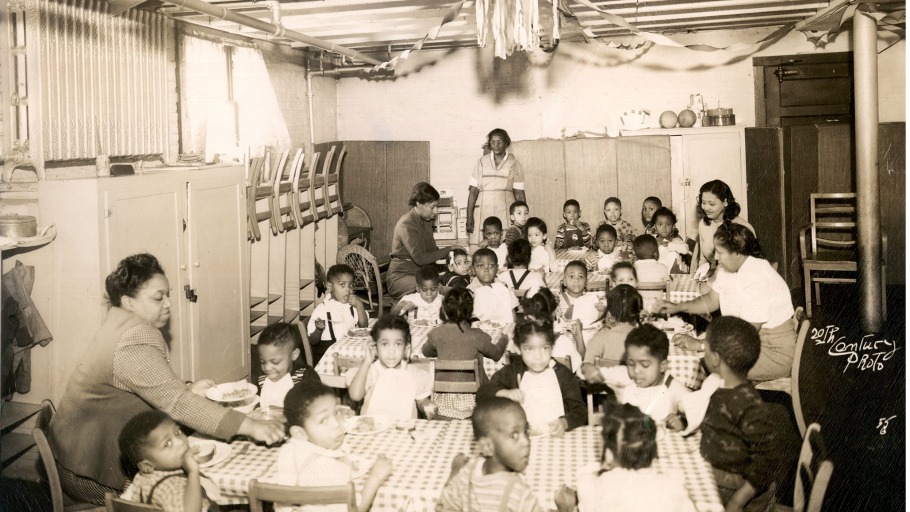

Children have snacks at a segregated day-care center in Evanston, circa 1940. Discrimination in education and housing continued in the city through much of the 20th century. (Shorefront Collection/Reuters)

Not everyone thinks the council’s approach is the right way to proceed. In the view of Alderwoman Cecily Fleming, choosing housing grants over cash payments is a form of discrimination itself. She voted no on Monday despite her support for reparations, saying the focus on housing confirms negative stereotypes that the poorest “can’t handle their money” and discriminates against people who may be due reparations but either don’t own a home or don’t plan to purchase one.

“I don’t think it’s true reparations. If we start out with something that is not clearly modeled after what historic reparations are about, we open up a lack of trust,” said Fleming, a longtime resident who is Black. “There’s no way I could go to African Americans in Mississippi who have experienced true racial terror and tell their city councils to do the same as what we’re doing with housing. I would be mortified.”

Tina Paden, who lives in the same house in downtown Evanston that her Black ancestors built in the late 1800s, thinks the disbursements for housing repair and mortgage assistance primarily benefit banks and other financial institutions. And those, she added, are the entities directly responsible for redlining and other discriminatory practices that the program is seeking to address.

“Reparations are supposed to repair harm to the injured parties. So if you’re telling someone what to do with the money, this appears to be a discriminatory practice as well. Now you have discrimination on discrimination,” she said.

She also supports reparations but would make cash payments to the city’s senior population the priority. “Why are you saying this 20-year-old can buy a new home in Evanston and the 80-year-old is still waiting?” she asked.

Daniel Biss, a former Illinois state senator who will be sworn in as Evanston‘s mayor in May, considers all options on the table for reparations, including cash payments. “There’s an incredible amount at stake here, and we have to do it thoroughly, inclusively and to get it right,” he said.

Principal Tamara Hadaway calls on one of her students at Kingsway Preparatory School in Evanston’s Fifth Ward. Hadaway founded the school partly because the Black community was the only ward without its own elementary school. (Eileen Meslar/Reuters)

Nationally, polls continue to show a dearth of support for reparations. A Reuters/Ipsos survey last summer found that only 20 percent of respondents agreed with using “taxpayer money to pay damages to descendants of enslaved people in the United States.” Support varied widely by race and political affiliation.

Biss, who is White, hopes the victory in his city will help to move the country forward.

“There’s a ton of progress to be made to get people to develop the fluency and the vocabulary to come to terms why arguments [against reparations] don’t hold water. That progress has to come from the grass roots up — from the neighborhoods, the municipalities and the states, and eventually the federal process in building that kind of pressure on the federal government,” he said.

Evanston “will be a small part of that,” he said. “We get to go first, but hopefully that will spur others to go soon.”

Source: The Washington Post