Harvard University sued over allegedly profiting from what are believed to be the earliest photos of American slaves.

Video — A lawyer says Harvard University has the opportunity to “remove the stain from its legacy” by honoring a Connecticut woman’s request to turn over photos of two South Carolina slaves she says are her ancestors. (March 20) AP, AP

BOSTON – In 1850, a Swiss-born Harvard University professor commissioned what are believed to be the earliest photos of American slaves.

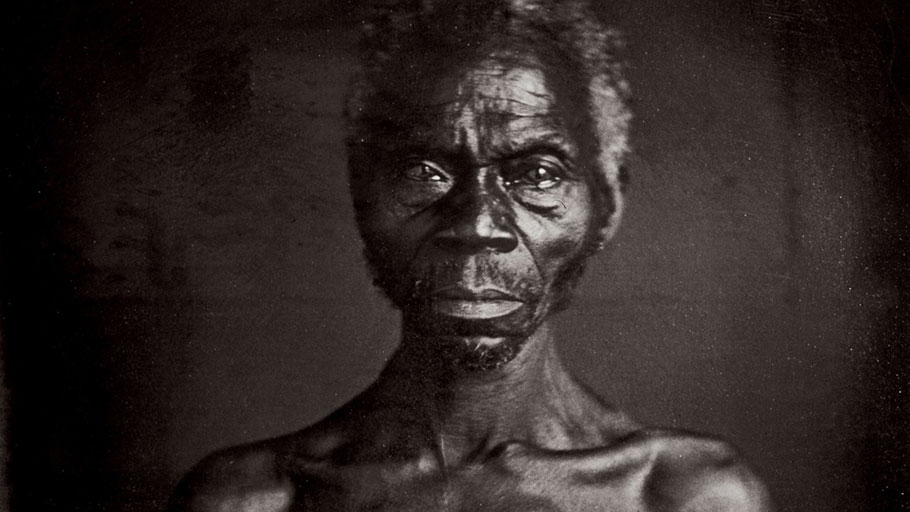

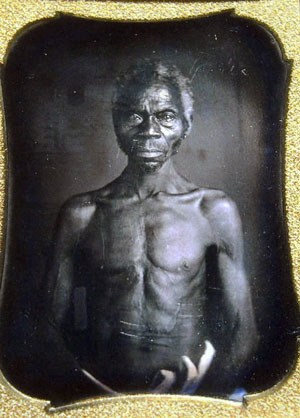

The images, known as daguerreotypes and taken in a South Carolina studio, are crude and dehumanizing – and they were used to promote racist beliefs.

Among the photographed: an African man named Renty and his daughter, Delia. They were stripped naked and photographed from several angles. Former professor Louis Agassiz, a biologist, had the photos taken to support an erroneous theory called polygenism that he and others used to argue that African-Americans were inferior to white people.

Now, a woman who says she is a direct descendant of that father and child – Tamara Lanier, the great-great-great granddaughter of Renty – is suing Harvard over the photos.

She has accused Harvard of the wrongful seizure, possession and monetization of the images, ignoring her requests to “stop licensing the pictures for the university’s profit” and misrepresenting the ancestor she calls “Papa Renty.”

The university still owns the photos. Lanier, who lives in Connecticut and filed the suit against Harvard in Middlesex County Superior Court on Wednesday, is seeking an unspecified amount of damages from Harvard. She’s also demanding that the university give her family the photos.

In an interview with USA TODAY, Lanier said she has presented Harvard with information about her direct lineage to Renty since around 2011, but the school has repeatedly turned down her requests to review the research.

“This will force them to look at my information,” Lanier said. “It will also force them to publicly have the discussion about who Renty was and restoring him his dignity.”

The suit, which lays out eight different legal claims, cites federal law over property rights, the Massachusetts law for the recovery of personal property and a separate state law about the unauthorized use of a name or picture for advertising purposes.

It also singles out the 13th Amendment to the Constitution, which abolished slavery, arguing that Harvard’s possession of the photos “reflects and is a continuation of core components or incidents of slavery.”

“For years, Papa Renty’s slave owners profited from his suffering. It’s time for Harvard to stop doing the same thing to our family,” Lanier said.

Who was Renty?

Lanier called Renty a “proud man who, like so many enslaved men, women and children endured years of unimaginable horrors.”

“Harvard’s refusal to honor our family’s history by acknowledging our lineage and its own shameful past is an insult to Papa Renty’s life and memory.”

The suit also says Harvard has “never sufficiently repudiated Agassiz and his work.”

Jonathan Swain, a spokesman for Harvard, said Wednesday that the university “has not yet been served, and with that is in no position to comment on this lawsuit filing.”

This July 17, 2018 copy photo shows a 1850 Daguerreotype of Renty, a South Carolina slave who Tamara Lanier said is her family’s patriarch. The portrait was commissioned by Harvard biologist Louis Agassiz, whose ideas were used to support the enslavement of Africans in the United States. (Photo: John Shishmanian, AP

Lanier is represented by the law firms of national civil rights attorney Benjamin Crump of Florida, who has worked high-profile cases for the families of Trayvon Martin and Michael Brown, as well as Connecticut-based attorney Michael Koskoff.

The photos taken in 1850 of Renty, Delia and 11 other slaves disappeared for more than a century but were rediscovered in 1976 in the attic of Harvard University’s Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology.

One of the photos of Renty, showing him waist-up as he looks defiantly into the camera, has four decades later turned into an iconic image of slavery in the U.S.

The lawsuit argues that Harvard has used the Renty images to “enrich itself.” The image is on the the cover of a 2017 book, “From Site to Sight: Anthropology, Photography and the Power of Imagery,” published by the Peabody Museum and sold online by Harvard for $40.

The photo also was displayed on the program for a 2017 conference that Harvard’s Radcliffe Institute for Advance Study hosted on the school’s relationship with slavery.

According to Lanier’s attorneys, Harvard requires that people sign a contract in order to view the photos and pay a licensing fee to the university to reproduce the images.

“These images were taken under duress, and Harvard has no right to keep them, let alone profit from them,” Koskoff said. “They are the rightful property of the descendants of Papa Renty.”

He accused Harvard of not wanting to tell the “full story” of how Renty’s image was seized – against the will of slaves for a professor who sought to “prove the inferiority” of the black race.

“Harvard continues to this day to honor him, and that’s an abomination,” Koskoff said.

In recent years, Harvard leaders have publicly acknowledged the school’s role in fostering slavery. In addition to the 2017 conference on slavery, the school convened a faculty committee a year earlier to jump-start scholarship and research on Harvard’s history with slavery.

Former University President Drew Faust said in a speech in 2016 that Harvard was “directly complicit” in America’s system of racial bondage until slavery was abolished in Massachusetts in 1783. She said Harvard remained “indirectly involved through extensive financial and other ties” to slavery in the South.

“This is our history and our legacy, one we must fully acknowledge and understand in order to truly move beyond the painful injustices at its core,” Faust said.

How the lawsuit began

The suit charts how Lanier, a former chief probation officer in Norwich, Connecticut, has on multiple occasion sought to engage the university about the photos to no avail.

Her attorneys say her effort began in 2011 when she wrote a letter to then-president Faust, whose “evasive response” did not provide an opportunity to discuss returning the photos to Lanier’s family.

Five years later, she says, she reached out to the student-run Harvard Crimson newspaper, but its editor relayed that the story had been “killed” because of concerns from the Peabody Museum.

In the university’s use of the images, the lawsuit says, Harvard has “avoided the fact that the daguerreotypes were part of a study, overseen by a Harvard professor, to demonstrate racial inferiority of blacks.”

“When will they not condone slavery and finally free Renty? Because their actions denote something different than what they might say,” Crump said.

“We are trying to tell as many people throughout America, and especially black people, that Renty does deserve the right to have his image. He was 169 years a slave, but based on this lawsuit, we sought to make sure he would be a slave no more.”

Agassiz was considered one of the greatest biologists and geologists in the world in the mid-19th century. But his record has become problematic over time. He was an opponent of Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution. And in fiercely subscribing to polygenism, he held the now-debunked belief that white people and African-Americans came from different species.

The photos he commissioned were taken by J.T. Zealy in a studio in Columbia, South Carolina. He published them a month later in an article titled “The Diversity of Origin of the Human Races.”

Agassiz’s legacy still lives on at Harvard. He founded the school’s Museum of Comparative Zoology, and his wife, Elizabeth Cary Agassiz, also a Harvard researcher of natural history, was founder and the first president of Radcliffe College, now the Society for the Collegiate Instruction of Women. A street in Cambridge is named after Agassiz, and so is a Harvard theater, the Agassiz House.

Lanier has spent recent years researching and talking to genealogical experts who she said have validated her ancestry.

Lanier said she began studying her family’s ancestry after her mother died in 2010 to follow up on family stories she heard about Papa Renty. She worked with Boston genealogist Chris Child, who is known for tracing ancestors of Barack Obama, according to a 2018 article in the Norwich Bulletin.

“It was a journey,” she said. “It was important to my mother that I write this story of who Papa Renty was down and to do a family tree.

“I made a promise to my mother,” she added.

According to the newspaper, Lanier said she can trace her great-grandfather, named Renty Taylor and then Renty Thompson, to a plantation near Columbia, South Carolina, owned by Benjamin Franklin Taylor. This is where the photos are believed to have been taken.

She said she started providing Harvard evidence that she’s a descendant of Renty but that the school has been “non-responsive.” “Most importantly, I want the true story of who Renty is to be told. That’s all I’ve ever asked for.”

The Bulletin quoted Pamela Gerardi, the Peabody Museum’s director of external relations, who described the photos last year as “extremely delicate” and well cared for.

“We anticipate they will remain here in perpetuity,” she said at the time. “That’s what museums do.”