Kids play basketball at Wilson Park near where Interstate 81 slices through a public housing complex in Syracuse, N.Y.

By Robert Samuels, Washington Post —

This city’s south side was devastated when a highway section went up. Now that there’s talk of taking it down, residents think they should be protected — and compensated.

SYRACUSE, N.Y. — When Ryedell Davis heard the 1.5-mile stretch of elevated highway slicing through this city might be torn down, he had a vision about what could emerge from its dust.

He could open a restaurant, near the one his grandparents had before it was bulldozed to make space for Interstate 81. Surrounding it could be other black-owned businesses, largely absent from the city’s south side because banks historically refused to give loans there. Maybe, he thought, the state would give them all tax credits or offer financial assistance to address the past injustice.

“We could have a little Africa,” said Davis, a 34-year-old liquor store owner who lives a few feet from the highway. “A black liquor store, a black grocery store, a black shopping center — places that used to exist before the highway.”

For Davis, reinvestment in his neighborhood is more than a dream; it is a form of reparation, a way for the city to atone for the damage the highway inflicted on this community.

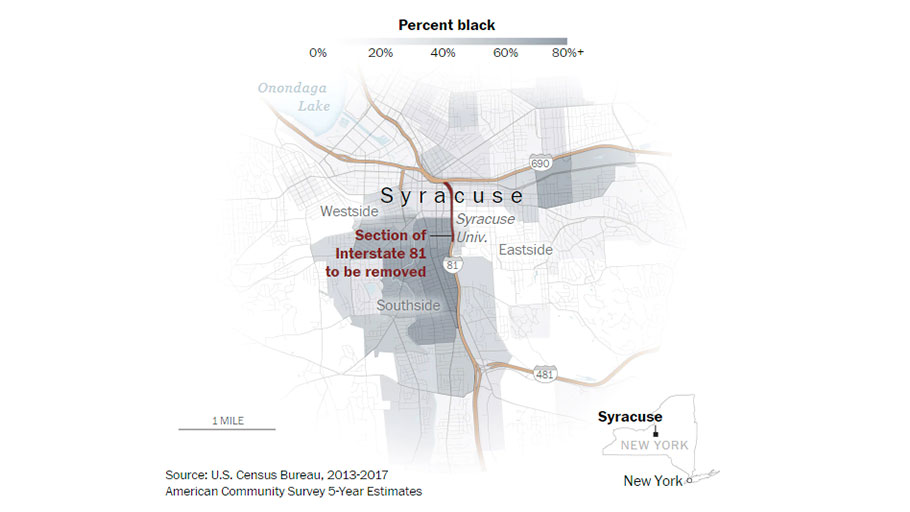

Source: U.S. Census Bureau, 2013-2017. American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates

For decades, discussions about reparations in this country have revolved around the merits and feasibility of handing checks to descendants of enslaved Americans. But there’s a growing interest, from activists to presidential candidates, to broaden the lens to include disparities in the criminal justice system, access to education and even infrastructure.

The spine of America — its railroads, runways and highways — was often literally built on top of black neighborhoods. Many of those communities had been segregated as a result of redlining and blighted because of a lack of credit. In the 1950s, they were destroyed in the name of urban renewal.

The Pioneer Homes housing complex sits a few feet away from an elevated part of highway that may soon be taken down. (Jahi Chikwendiu/The Washington Post)

More than a half-century later, some of those runways and highways are crumbling beyond repair. In Syracuse, residents are trying to leverage officials’ desire to do something about their old road into an opportunity to repair ills of the past.

“We’re saying that neighborhood that you destroyed was in fact the slums because you made it that way,” said Lanessa Chaplin, a lawyer and organizer with the American Civil Liberties Union. “So now you have to fix it.”

If the reparations debate in this country continues to move beyond handing out checks, the ensuing debate over Interstate 81 presages a bevy of challenges that await.

South side residents who support the decision to take down the highway say simply removing a slab of concrete wouldn’t be enough to undo the damage.

In a community accustomed to being on the losing end of the government’s ambitions, residents fretted that the city’s plan might leave them worse off.

“What going to happen to us?” Bebe Baines, 62, asked her husband, Lloyd, as they sat on their front porch across the street from the highway.

Bebe Baines, left, and husband Lloyd Baines sit with neighbor David Abdul Sabur, center, on their front porch that is only a stone’s throw from I-81. (Jahi Chikwendiu/The Washington Post)

The Baines family has lived on the south side for more than 25 years. The homeowners here say they were the best houses that families could get when banks were cautious about lending to African Americans. Neighbors helped each other renovate their kitchens and paint their front porches.

On this side of the highway, teenagers play basketball steps from I-81’s underbelly. Neighbors complain drug dealers sometimes lurk in the shadows. There are empty roads, some pharmacies and fast-food restaurants, and homes that bare the dust and grime from highway exhaust. The rate of asthma hospitalizations for children are already twice as high in the city as they are in the suburbs.

New York officials say they are early in the process but have vowed to address the concerns of the south side. They say tearing down the section of road that divides the community will help everyone in the city by removing an unsightly barrier and reducing accidents.

Lloyd Baines, 65, was worried, too. On the other side of the highway, developers were building luxury houses for college students and putting up glistening hospital buildings. He’s nervous his neighborhood could be the real estate market’s next frontier if the barrier gets removed.

“If this place gentrifies, those developers are going to charge whatever they want and raise all my property taxes,” he said. “If they cared about us, they would freeze our taxes to keep things fair.”

In the 1950s, New York started knocking down houses on Syracuse’s south side to build I-81. (Jahi Chikwendiu/The Washington Post)

“Maybe they should just buy us out,” said Bebe Baines, who has chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. “Compensate us for everything and then we don’t have to breathe in this bad air anymore. I don’t want to sound grabby, but I just want to make sure we are healthy.”

Behind her, cars zoomed. She looked at her husband and asked: “Have you ever noticed how cities always have a south side?”

I-81 slices through this predominantly African American community of Victorian-style homes. (Jahi Chikwendiu/The Washington Post)

If not a “south side,” then a “west side” or a “neighborhood across the tracks” — phrases that are less about geography and more of a euphemism for a demographic divide.

The divide is particularly stark in Syracuse, which has some of the highest concentrations of blacks and Hispanics living in poverty in the country, according to Sally Santangelo, executive director of nonprofit legal group CNY Fair Housing.

“When I give presentations in the suburbs, everyone is surprised at the statistic,” Santangelo said. “When I give it in the actual city, no one is surprised.”

One recent evening, Santangelo gave a presentation about the south side’s history at a local library. Before the highway, the area was known as the 15th Ward. It was a predominantly Jewish neighborhood until blacks from the South migrated in the 1900s to seek manufacturing jobs.

Eventually, the neighborhood changed. Santangelo pulled up a slide that illustrated why. It showed a copy of a residential covenant prohibiting blacks from moving into a particular neighborhood, then a common practice in Syracuse. Similar restrictions were placed in deeds and in guidelines for real estate agents.

Because there were few options for African Americans seeking to move out of the 15th Ward, the neighborhood became overwhelmingly black as Jewish families moved away.

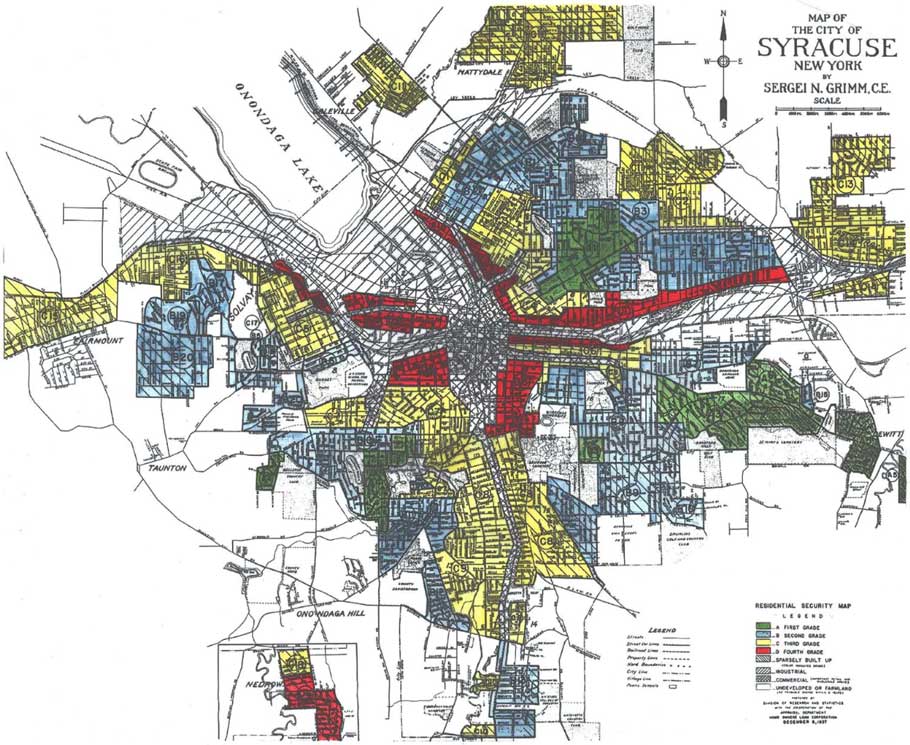

Santangelo pulled up another slide. This one showed a color-coded map from 1937 by the federal Home Owners’ Loan Corp. The banks put a green dot on areas considered low risk — which signaled an easy process to obtain a loan — and a red dot on high-risk investments, making it nearly impossible to gain one. A large red band ran through the 15th Ward.

A color-coded map from 1937 shows red dots meant to represent high-risk investment areas.

Unable to use banks for equity, families in the 15th Ward saw their housing stock fall into blight and disrepair.

When the federal government started distributing millions for urban renewal projects, the city declared the redlined areas “slums” and began to clear them out.

“The same neighborhoods they declared blighted?” one person asked.

“Yes,” Santangelo said.

She looked back at the map.

“Does anyone notice anything about those redlines?” Santangelo asked.

“It looks like the highway,” someone in the audience said.

“That’s right,” Santangelo replied. “That’s where the highways are.”

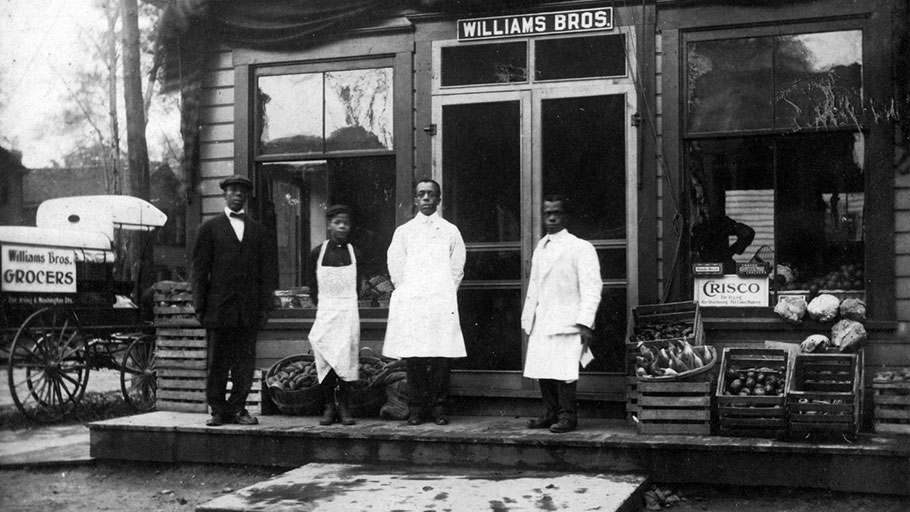

As Santangelo ran through the slides, a 73-year-old neighborhood activist, Charlie Pierce-El, ran through his childhood. His was one of those migratory families — his parents came from Georgia. He remembers other black families planting vegetables in their gardens and setting up businesses of their own. They bought groceries at Mr. Betsy’s and saw Dr. Washington when they weren’t feeling well, or ate at Davis’s restaurant.

The Williams brothers stand outside their grocery store in Syracuse’s 15th Ward in 1920. The neighborhood was once home to many businesses owned by African Americans. (Onondaga Historical Association/Onondaga Historical Association)

A woman walks past Schor’s Market on Harrison Street in Syracuse’s 15th Ward in 1965. (Onondaga Historical Association/Onondaga Historical Association)

In the late 1950s, life got bleak. Pierce-El remembered the stories of people who came home to notice government officials had drawn X’s on their houses, meaning they would have to move to another place. When President Dwight D. Eisenhower started an initiative to build the national highway system, the state knocked down those houses.

Similar events happened near Lambert International Airport in St. Louis, along the Cypress Freeway in Oakland,, along interstates in Miami and Wilmington, in Nashville, Detroit, Buffalo, New Orleans.

There were protests in these communities, but the residents had little political power to stop the plans. In a segregated world, it was extraordinarily rare to have black members on the city council or the state transportation boards. And civil rights organizations were consumed by the fight for voting rights.

Pierce-El watched the places he loved start to disappear. Soon, there wasn’t a Davis’s restaurant, nor Dr. Washington’s office, nor Mr. Betsy’s grocer.

The people he loved started to leave, too. Many houses had been replaced with cinder blocks, nuts and bolts to hoist up the highway. With fewer housing options, many found jobs in other redlined towns.

Homes and wealth were lost. Ninety percent of the structures in the 15th Ward were torn down, according to documents for the county’s historic society. Between 400 and 500 businesses were gone. Around 1,200 families were displaced.

When housing discrimination became illegal, wealthier white families drove the highway out of town and built up the suburbs. In the city, homes sunk into blight, roads worsened and a resentment festered among black residents.

“They destroyed the strength and power we had,” Pierce-El said. “They took it all away.”

Danny Freeman, 81, and Mike Atkins, 70, right, grew up in the 15th Ward until the neighborhood was razed to build I-81. (Jahi Chikwendiu/The Washington Post)

Toward the end of the Obama administration, Transportation Secretary Anthony Foxx initiated a “design challenge” for communities to help mitigate the impact of infrastructure projects on low-income communities. The program was not revived during the Trump administration, which has preferred to attempt to boost investment in low-income neighborhoods through tax breaks in economically distressed areas it has labeled “Opportunity Zones.”

As Democratic presidential candidates respond to the questions about their thoughts on reparations, many home in on segregated communities like the south side.

South Bend, Ind., Mayor Pete Buttigieg has called for increasing access to credit in black communities and increasing training for black entrepreneurs. Sens. Cory Booker (N.J.) and Kamala D. Harris (Calif.) want to offer tax credits for low- and middle-income families that they say would decrease the racial wealth gap.

Sens. Elizabeth Warren (Mass.) and Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.) have addressed the impact of redlining. Former vice president Joe Biden has said he is interested in studying the issue of giving checks to descendants of slaves, but supports “tak[ing] action to deal with the systemic things that still exist in housing and insurance and a whole range of things that make it harder for African Americans.”

One of those things is the highway.

Capone, Celeste Wallace and 3-year-old Ezekiel Wallace sit on their porch at Pioneer Homes.

Willa Hatcher wipes traffic soot from the walls in her high-rise apartment that sits near I-81.

As night falls, Kendo relaxes near I-81 with friends and neighbors.

The Davis family lost its restaurant, but the love of cooking never left. Davis and his mother sold dinners from their home and held barbecues for the children around the neighborhood who had grown used to playing in the shadows of the highway.

“I used to think it was just normal living by a highway,” said Davis, who grew up with asthma. “But now I think about all its effects and how it influenced my family. It needs to come down.”

If the plans proceed, four buildings, none of them historic, would have to be knocked down, according to an early state project report. The state would offer families hotel rooms for days when they are at risk of breathing in bad air. And meetings are being held throughout the area to incorporate community feedback so the Transportation Department can assure residents that this infrastructure project won’t be like the last.

One recent afternoon, Bebe and Lloyd Baines drove to attend a meeting about I-81 at the city convention center. A small band of protesters with “Save I-81!” signs stood outside.

Most of the protesters were from the suburbs, worried that the removal of the highway would tie them up in traffic and elongate their commutes.

“I find that complaint offensive,” Lloyd Baines said. “Our community is the one that has been suffering.”

Inside, there were more than 1,000 people, walking around large poster boards of traffic grids. The charts they saw focused on estimated changes to commute times from the suburbs. The Baines couple didn’t see any poster boards on the noise, the environmental hazards, the taxes, the trauma. For them, it felt like other communities’ needs were again being placed ahead of their own.

Until becoming aware of the dangers of living in close proximity to traffic fumes, Ryedell Davis said he thought his asthma was hereditary. (Jahi Chikwendiu/The Washington Post)

Laura Tanyhill, Bebe Baines, Betty Webb and Shellie Scott meet at Pentecost Evangelical Missionary Baptist Church. (Jahi Chikwendiu/The Washington Post)

They looked around at the staff members circling the floor and surmised why.

“Most of them don’t look like us,” Lloyd Baines said to his wife. “Not to say it makes a difference, but I just would feel that they would know what we are going through if they had more of us.”

Mark Frechette, who is overseeing the I-81 project, took the stage. He described the plan to reroute traffic to a business loop on the outskirts of the city.

He spoke for about five minutes. This meeting, Frechette told the audience, was just the beginning of a years-long community process to reimagine the city. After he spoke, official after official reiterated the same message to the crowd: “This is a once-in-a-generation opportunity.”

Lloyd Baines looked at Bebe. Soon, they were on their way back home and back to their rocking chairs on the front porch, with the same question they had when they left: An opportunity for whom?

Octavia Scudder, center, watches Aaliyah, left, and A’mora as they walk near I-81. (Jahi Chikwendiu/The Washington Post)