States and cities weigh compensation and fixing broken systems.

By April Simpson, Center for Public Integrity —

Georgia state Sen. Kim Jackson has pretty much given up on the idea that Black Georgians might some day receive reparations for past injustices.

“In Georgia, the concept of reparations is a politically dead issue. It will not move,” said Jackson, a Black woman who comes from a farming family and sits on the Senate Agriculture and Consumer Affairs Committee.

But leap across the country to California, a leader in this regard. The state launched a Reparations Task Force last year, and is compensating survivors of state-sponsored sterilization. While California is looking comprehensively, advocates in Republican-controlled states like Georgia are hoping for a narrower victory focused on farmers.

While Jackson supports reparations on a philosophical level, she’s aware of the political realities in her state. “So we have to take the steps that we can take, which is bringing farmers to parity,” she said.

Reparations are an old argument, fought mostly on the national stage. In recent years, however, state and local governments have gotten around the sticky point of who would get money by focusing on descendants of specific latter-day policies, rather than the much broader set of injustices Black Americans have faced since before the nation’s founding.

Some argue that a $4 billion provision to cancel the debts of farmers of color in the American Rescue Plan Act Congress passed last year is simply reparations by another name. It’s stalled in the courts over a basic argument over whether and how to compensate people for past injustices.

Loans are essential to farming, a capital-intensive environment that requires expensive equipment and healthy access to credit. In the agriculture community, crushing debt is a contemporary legacy — like discriminatory lending for housing, forced sterilization, and gentrification caused by freeway construction — for which many advocates say Black farmers should be compensated.

“If we want to have future generations of Black farmers, then forgiving this debt helps to open up a pathway for new generations of farmers to pick up where their parents or grandparents left off because they won’t be inheriting massive amounts of debt,” Jackson said.

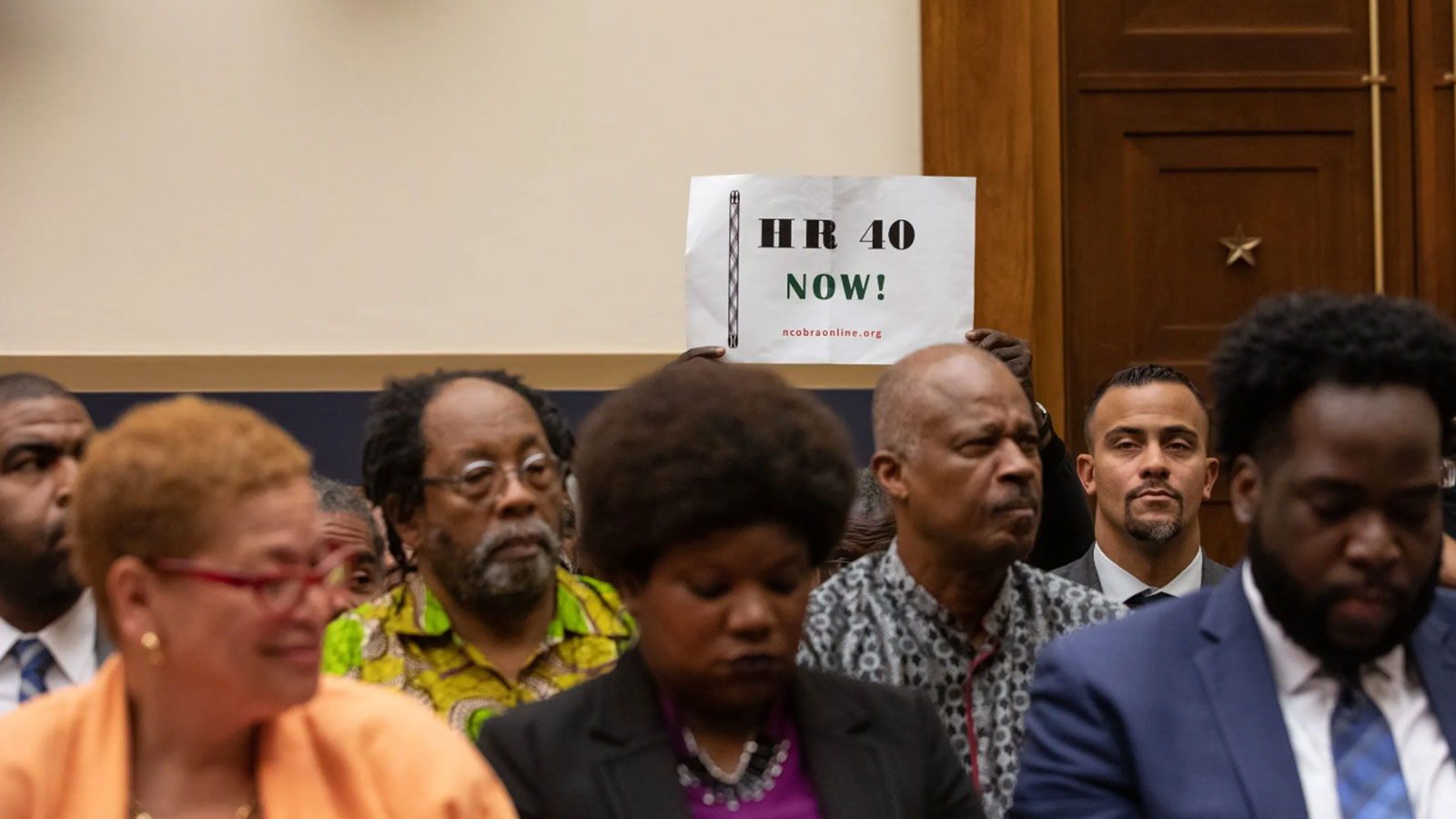

An attendee holds up a sign in support of HR 40, during the hearing on reparations for the descendants of slaves before the House Judiciary Subcommittee on the Constitution, Civil Rights and Civil Liberties, on Capitol Hill in Washington, D.C., on June 19, 2019. (Cheriss May/NurPhoto via Getty Images)

Modern legislation addressing the idea of reparations has been stalled in Congress for decades. H.R. 40 is named after the post-emancipation promise of 40 acres and a mule for the formerly enslaved made by Gen. Tecumseh Sherman as he was marching through Georgia. The program was immediately revoked by President Andrew Johnson, who succeeded Abraham Lincoln after he was assassinated. The bill, first introduced in 1989 by the late U.S. Rep John Conyers of Michigan, would commission a study on the effects of slavery and racial discrimination and develop reparations proposals for African Americans. For the first time last year, it was approved by the House Judiciary Committee, but it has yet to reach the floor for a vote.

Jackson knows that the chances of adopting any kind of compensation to Black farmers using state funds are slim as long as Georgia is ruled by a Republican state legislature and governor. Republicans in Georgia and nationally have expressed fierce opposition to policies that seek to correct the consequences of past discrimination. U.S. Sen. Minority Leader Mitch McConnell has said he opposes reparations for slavery since “none of us currently living are responsible.”

But not so in California, which is controlled by Democrats and where non-Hispanic white residents make up a minority of the state population. An interim report by the state’s Reparations Task Force calls for implementing a “comprehensive reparations scheme,” including policies to “compensate for the harms caused by the legacy of anti-Black discrimination.”

Preliminary recommendations include compensating individuals forcibly removed from their homes for park or highway construction, families who were denied inheritances because of anti-miscegenation laws or precedents; and those whose mental and physical health has been permanently damaged by health care system policies and treatment.

In December, the state described how it will divide $4.5 million among survivors of state-sponsored sterilization programs involving eugenics and forced-sterilization of women in state penal institutions, tying the funds to specific individuals who were hurt by the state.

Evanston, Illinois, is another standout. It received considerable national attention last year when it agreed to pay reparations to people affected by discrimination in lending, zoning laws and practices between 1916 and 1969. Residents or descendants of those who were discriminated against are eligible for up to $25,000 in grants to purchase a home, upgrade their home or assist with their mortgage. The effort is funded by city tax from the sale of recreational cannabis.

A man walks by a sign welcoming people to the city of in Evanston, Illinois, on March 16, 2021. The Chicago suburb provides reparations to its Black residents, with a plan to distribute $10 million over the next decade. (Kamil Krzaczynski/AFP via Getty Images)

“There is precedent,” Robin Rue Simmons said in a panel last month moderated by the Brookings Institution, a Washington, D.C.-based think tank focused on public policy. Simmons is founder and executive director of FirstRepair, a not-for-profit that advocates for local reparations nationally, and a former fifth ward alderman for the city of Evanston. “Most examples of radical policy change start with the local initiative and there is no difference here with what we’re seeing with the local reparations movement.”

Nashville is considering how reparations can help to ameliorate harm from construction on parts of Interstate Highway I-40 that in the late 1960s wiped out a once thriving Black community that included four historically Black colleges and universities and successful small businesses.

Similar efforts are being studied in Asheville, North Carolina; Greenbelt, Maryland, a suburb of the nation’s capital; and Detroit.

A number of states are taking a closer look at racial equity in agriculture specifically, and attempting to reform existing systems.

Since the 2020 uprisings for racial justice, at least five states have introduced bills to stem Black land loss, but proposals in all but Illinois have died in committee. In Vermont, a proposal that included creating a Land Access and Opportunity Board was approved in a separate bill.

A bill in Georgia would have created an office within the Georgia Department of Agriculture to encourage the growth of Black farmers and bring “oversight and accountability.”

“I don’t think it’s a reparations bill,” said state Rep. Kim Schofield, a Georgia Democrat who sponsored it.

“I’m not trying to go back and undo all the unfairness you have already done. We know that. I’m trying to take the system that has been broken for so long and make it better because it’s the right thing to do. It doesn’t separate the fact that you took from us. What it says to me is it’s about time we were all included in improving the quality of life for all Georgians.”

Source: Center for Public Integrity

Featured image: People listen as Newark Mayor Ras Baraka speaks during a Juneteenth reparations rally at City Hall on June 17, 2022. Rally-goers called on New Jersey lawmakers to pass legislation to establish a Reparations Task Force that would study and propose policy recommendations for reparative justice. (Michael M. Santiago/Getty Images)