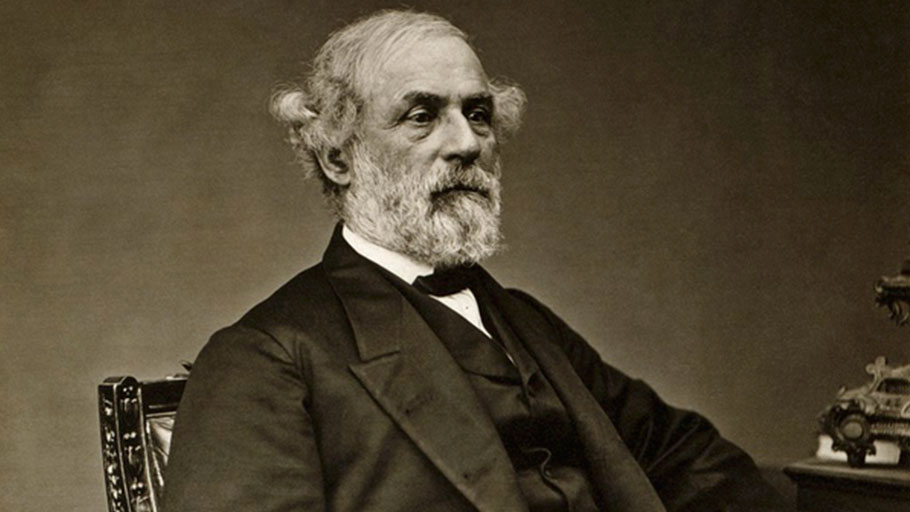

There’s a fabled moment from the Battle of Fredericksburg, a gruesome Civil War battle that extinguished several thousand lives, when the commander of a rebel army looked down upon the carnage and said, “It is well that war is so terrible, or we should grow too fond of it.” That commander, of course, was Robert Lee.

The moment is the stuff of legend. It captures Lee’s humility (he won the battle), compassion, and thoughtfulness. It casts Lee as a reluctant leader who had no choice but to serve his people, and who might have had second thoughts about doing so given the conflict’s tremendous amount of violence and bloodshed. The quote, however, is misleading. Lee was no hero. He was neither noble nor wise. Lee was a traitor who killed United States soldiers, fought for human enslavement, vastly increased the bloodshed of the Civil War, and made embarrassing tactical mistakes.

1) Lee was a traitor

Robert Lee was the nation’s most notable traitor since Benedict Arnold. Like Arnold, Robert Lee had an exceptional record of military service before his downfall. Lee was a hero of the Mexican-American War and played a crucial role in its final, decisive campaign to take Mexico City. But when he was called on to serve again—this time against violent rebels who were occupying and attacking federal forts—Lee failed to honor his oath to defend the Constitution. He resigned from the United States Army and quickly accepted a commission in a rebel army based in Virginia. Lee could have chosen to abstain from the conflict—it was reasonable to have qualms about leading United States soldiers against American citizens—but he did not abstain. He turned against his nation and took up arms against it. How could Lee, a lifelong soldier of the United States, so quickly betray it?

2) Lee fought for slavery

Robert Lee understood as well as any other contemporary the issue that ignited the secession crisis. Wealthy white plantation owners in the South had spent the better part of a century slowly taking over the United States government. With each new political victory, they expanded human enslavement further and further until the oligarchs of the Cotton South were the wealthiest single group of people on the planet. It was a kind of power and wealth they were willing to kill and die to protect.

According to Northwest Ordinance of 1787, new lands and territories in the West were supposed to be free while largescale human enslavement remained in the South. In 1820, however, Southerners amended that rule by dividing new lands between a free North and slave South. In the 1830s, Southerners used their inflated representation in Congress to pass the Indian Removal Act, an obvious and ultimately successful effort to take fertile Indian land and transform it into productive slave plantations. The Compromise of 1850 forced Northern states to enforce fugitive slave laws, a blatant assault on the rights of Northern states to legislate against human enslavement. In 1854, Southerners moved the goal posts again and decided that residents in new states and territories could decide the slave question for themselves. Violent clashes between pro- and anti-slavery forces soon followed in Kansas.

The South’s plans to expand slavery reached a crescendo in 1857 with the Dred Scott Decision. In the decision, the Supreme Court ruled that since the Constitution protected property and enslaved humans were considered property, territories could not make laws against slavery.

The details are less important than the overall trend: in the seventy years after the Constitution was written, a small group of Southerner oligarchs took over the government and transformed the United States into a pro-slavery nation. As one young politician put it, “We shall lie pleasantly dreaming that the people of Missouri are on the verge of making their State free; and we shall awake to the reality, instead, that the Supreme Court has made Illinois a slave State.”

The ensuing fury over the expansion of slave power in the federal government prompted a historic backlash. Previously divided Americans rallied behind a new political party and the young, brilliant politician quoted above. Abraham Lincoln presented a clear message: should he be elected, the federal government would no longer legislate in favor of enslavement, and would work to stop its expansion into the West.

Lincoln’s election in 1860 was not simply a single political loss for slaveholding Southerners. It represented a collapse of their minority political dominance of the federal government, without which they could not maintain and expand slavery to full extent of their desires. Foiled by democracy, Southern oligarchs disavowed it and declared independence from the United States.

Their rebel organization—the “Confederate States of America,” a cheap imitation of the United States government stripped of its language of equality, freedom, and justice—did not care much for states’ rights. States in the Confederacy forfeited both the right to secede from it and the right to limit or eliminate slavery. What really motivated the new CSA was not only obvious, but repeatedly declared. In their articles of secession, which explained their motivations for violent insurrection, rebel leaders in the South cited slavery. Georgia cited slavery. Mississippi cited slavery. South Carolina cited the “increasing hostility… to the institution of slavery.” Texas cited slavery. Virginia cited the “oppression of… Southern slaveholding.” Alexander Stephens, the second in command of the rebel cabal, declared in his Cornerstone Speech that they had launched the entire enterprise because the Founding Fathers had made a mistake in declaring that all people are made equal. “Our new government is founded upon exactly the opposite idea,” he said. People of African descent were supposed to be enslaved.

Despite making a few cryptic comments about how he refused to fight his fellow Virginians, Lee would have understood exactly what the war was about and how it served wealthy white men like him. Lee was a slave-holding aristocrat with ties to George Washington. He was the face of Southern gentry, a kind of pseudo royalty in a land that had theoretically extinguished it. The triumph of the South would have meant the triumph not only of Lee, but everything he represented: that tiny, self-defined perfect portion at the top of a violently unequal pyramid.

Yet even if Lee disavowed slavery and fought only for some vague notion of states’ rights, would that have made a difference? War is a political tool that serves a political purpose. If the purpose of the rebellion was to create a powerful, endless slave empire (it was), then do the opinions of its soldiers and commanders really matter? Each victory of Lee’s, each rebel bullet that felled a United States soldier, advanced the political cause of the CSA. Had Lee somehow defeated the United States Army, marched to the capital, killed the President, and won independence for the South, the result would have been the preservation of slavery in North America. There would have been no Thirteenth Amendment. Lincoln would not have overseen the emancipation of four million people, the largest single emancipation event in human history. Lee’s successes were the successes of the Slave South, personal feelings be damned.

If you need more evidence of Lee’s personal feelings on enslavement, however, note that when his rebel forces marched into Pennsylvania, they kidnapped black people and sold them into bondage. Contemporaries referred to these kidnappings as “slave hunts.”

3) Lee was not a military genius

Despite a mythology around Lee being the Napoleon of America, Lee blundered his way to a surrender. To be fair to Lee, his early victories were impressive. Lee earned command of the largest rebel army in 1862 and quickly put his experience to work. His interventions at the end of the Peninsula Campaign and his aggressive flanking movements at the Battle of Second Manassas ensured that the United States Army could not achieve a quick victory over rebel forces. At Fredericksburg, Lee also demonstrated a keen understanding of how to establish a strong defensive position, and foiled another US offensive. Lee’s shining moment came later at Chancellorsville, when he again maneuvered his smaller but more mobile force to flank and rout the US Army. Yet Lee’s broader strategy was deeply flawed, and ended with his most infamous blunder.

Lee should have recognized that the objective of his army was not to defeat the larger United States forces that he faced. Rather, he needed to simply prevent those armies from taking Richmond, the city that housed the rebel government, until the United States government lost support for the war and sued for peace. New military technology that greatly favored defenders would have bolstered this strategy. But Lee opted for a different strategy, taking his army and striking northward into areas that the United States government still controlled.

It’s tempting to think that Lee’s strategy was sound and could have delivered a decisive blow, but it’s far more likely that he was starting to believe that his men truly were superior and that his army was essentially unstoppable, as many supporters in the South were openly speculating. Even the Battle of Antietam, an aggressive invasion that ended in a terrible rebel loss, did not dissuade Lee from this thinking. After Chancellorsville, Lee marched his army into Pennsylvania where he ran into the United States Army at the town of Gettysburg. After a few days of fighting into a stalemate, Lee decided against withdrawing as he had done at Antietam. Instead, he doubled down on his aggressive strategy and ordered a direct assault over open terrain straight into the heart of the US Army’s lines. The result—several thousand casualties—was devastating. It was a crushing blow and a terrible military decision from which Lee and his men never fully recovered. The loss also bolstered support for the war effort and Lincoln in the North, almost guaranteeing that the United States would not stop short of a total victory.

4) Lee, not Grant, was responsible for the staggering losses of the Civil War

The Civil War dragged on even after Lee’s horrific loss at Gettysburg. Even after it was clear that the rebels were in trouble, with white women in the South rioting for bread, conscripted men deserting, and thousands of enslaved people self-emancipating, Lee and his men dug in and continued to fight. Only after going back on the defensive—that is, digging in on hills and building massive networks of trenches and fortifications—did Lee start to achieve lopsided results again. Civil War enthusiasts often point to the resulting carnage as evidence that Ulysses S. Grant, the new General of the entire United States Army, did not care about the terrible losses and should be criticized for how he threw wave after wave of men at entrenched rebel positions. In reality, however, the situation was completely of Lee’s making.

As Grant doggedly pursued Lee’s forces, he did his best to flush Lee into an open field for a decisive battle, like at Antietam or Gettysburg. Lee refused to accept, however, knowing that a crushing loss likely awaited him. Lee also could have abandoned the area around the rebel capital and allowed the United States to achieve a moral and political victory. Both of these options would have drastically reduced the loss of life on both sides and ended the war earlier. Lee chose neither option. Rather, he maneuvered his forces in such a way that they always had a secure, defensive position, daring Grant to sacrifice more men. When Grant did this and overran the rebel positions, Lee pulled back and repeated the process. The result was the most gruesome period of the war. It was not uncommon for dead bodies to be stacked upon each other after waves of attacks and counterattacks clashed at the same position. At the Wilderness, the forest caught fire, trapping wounded men from both sides in the inferno. Their comrades listened helplessly to the screams as the men in the forest burned alive.

To his credit, when the war was truly lost—the rebel capital sacked (burned by retreating rebel soldiers), the infrastructure of the South in ruins, and Lee’s army chased one hundred miles into the west—Lee chose not to engage in guerrilla warfare and surrendered, though the decision was likely based on image more than a concern for human life. He showed up to Grant’s camp, after all, dressed in a new uniform and riding a white horse. So ended the military career of Robert Lee, a man responsible for the death of more United States soldiers than any single commander in history.

***

So why, after all of this, do some Americans still celebrate Lee? Well, many white Southerners refused to accept the outcome of the Civil War. After years of terrorism, local political coups, wholesale massacres, and lynchings, white Southerners were able to retake power in the South. While they erected monuments to war criminals like Nathan Bedford Forrest to send a clear message to would-be civil rights activists, white southerners also needed someone who represented the “greatness” of the Old South, someone of whom they could be proud. They turned to Robert Lee.

But Lee was not great. In fact, he represented the very worst of the Old South, a man willing to betray his republic and slaughter his countrymen to preserve a violent, unfree society that elevated him and just a handful of others like him. He was the gentle face of a brutal system. And for all his acclaim, Lee was not a military genius. He was a flawed aristocrat who fell in love with the mythology of his own invincibility.

After the war, Robert Lee lived out the remainder of his days. He was neither arrested nor hanged. But it is up to us how we remember him. Memory is often the trial that evil men never received. Perhaps we should take a page from the United States Army of the Civil War, which needed to decide what to do with the slave plantation it seized from the Lee family. Ultimately, the Army decided to use Lee’s land as a cemetery, transforming the land from a site of human enslavement to a final resting place for United States soldiers who died to make men free. You can visit that cemetery today. After all, who hasn’t heard of Arlington Cemetery?

This article was originally published by the History News Network.

Michael McLean is a PhD candidate in history at Boston College.