In the fall of 2014, Georgetown University’s student newspaper, the Hoya, ran an article by undergraduate columnist Matthew Quallen titled “Georgetown, Financed by Slave Trading.” Published the month after the killing of Michael Brown by police officer Darren Wilson in Ferguson, Missouri, and amid the rise of the Black Lives Matter movement, Quallen’s article discussed Jesuit slaveholding and Georgetown’s implication in the slave trade—a history he had learned by chance during a campus tour in his first year of college. The article focused specifically on the 1838 sale of 272 individuals who had been enslaved on Jesuit plantations in and around Maryland. The profits from this sale helped the struggling Jesuit college emerge from substantial debt and paved the way for it to flourish into the institution it is today.

This was the first time many people had heard of Georgetown’s intimate involvement with the slave trade, and it was galvanizing: student activists led a successful campaign to rename two campus buildings that bore the names of the 1838 sale’s architects. In September 2015, the university formed a Working Group on Slavery, Memory, and Reconciliation. The New York Times published a series of articles examining Jesuit slaveholding and the sale. An organization unaffiliated with the university, the Georgetown Memory Project, began using genealogical research and DNA testing to identify descendants of the 272 individuals sold to slavers in Louisiana. And a robust community of these descendants began organizing, pressing both Georgetown and the Jesuits for information, accountability, and action.

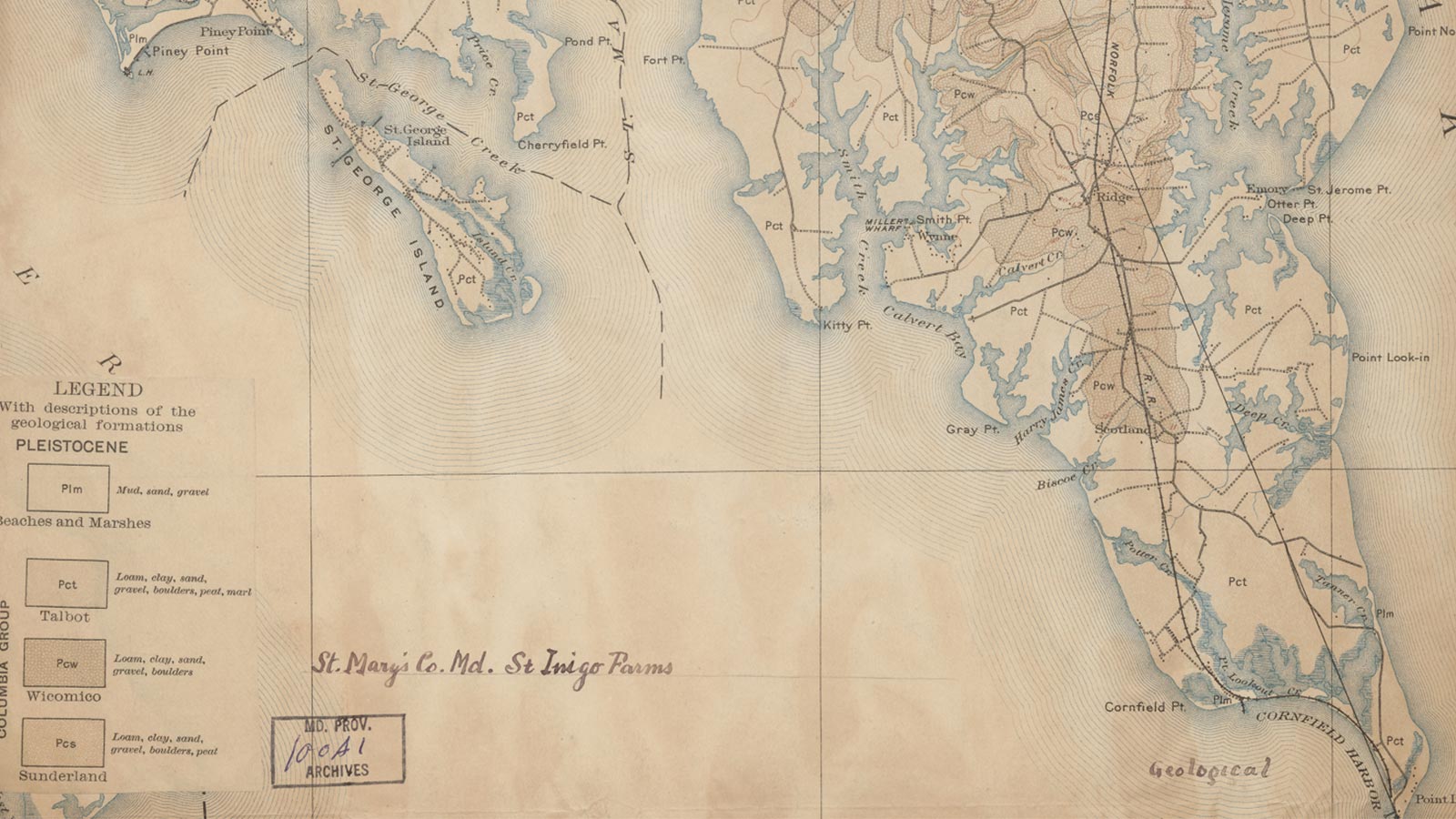

Just because information is available does not mean it is accessible, a problem that staff working with the Maryland Province Archives at Georgetown University have been attempting to address. Map of St. Mary’s County, Maryland, St. Inigo Farms, Archives of the Maryland Province of the Society of Jesus. Public domain.

Before the Hoya article, the history of Jesuit slaveholding in North America had not in fact been a secret. Members of the Jesuit community had written about the sale, mostly in passing, since the early 20th century, and a handful of non-Jesuit scholars had been scrutinizing it in varying levels of detail since the 1990s. Always meticulous record keepers, the Jesuits of the Maryland Province maintained significant documentation of their slaveholding past: plantation accounts, financial records, personal reflections on the institution of slavery in diaries and correspondence, and sacramental records that documented births, baptisms, and marriages of enslaved individuals. There were also copious papers related to the 1838 sale, including a remarkably detailed census listing the 272 enslaved people to be sold, featuring individuals’ names, ages, family relationships, plantation affiliations, and, penciled in later, a numerical code indicating which ship transported them in their forced journey to the South.

These records are part of the Archives of the Maryland Province of the Society of Jesus. This wide-ranging collection documents the Jesuit presence in North America since the 1600s, and has been held at Georgetown since 1977, though it remains the property of the Jesuits. Although some materials have been and remain restricted—primarily those created in the latter half of the 20th century—the collection, including materials pertaining to slavery, has been at least nominally available to scholars, students, and genealogists since its arrival at Georgetown.

This wide-ranging collection documents the Jesuit presence in North America since the 1600s.

Even so, the history of Jesuit slaveholding and the story of Georgetown’s reliance on the profits of the 1838 sale were too little discussed; the barriers to accessing the archives documenting this history were too great. Materials could only be used on-site by those with the ability to travel to Georgetown. The collection’s previous finding aids could be obtuse even to seasoned researchers, and they did not always clearly identify materials pertaining to Jesuit slaveholding. And more fundamentally, archival repositories, whether consciously or not, have often been unwelcoming to members of historically marginalized groups.

Georgetown’s Working Group recognized early on that the Maryland Province Archives needed to be a central component of the university’s slavery, memory, and reconciliation efforts. In response, history professor Adam Rothman launched the Georgetown Slavery Archive, a digital repository featuring key documents from the Maryland Province Archives, the University Archives, and other collections that illuminated the history of Jesuit slaveholding, Georgetown’s relationship to slavery, and the 1838 sale. Rothman and a team of graduate students have combed the Maryland Province Archives to find materials, photographing, translating, and transcribing the slavery-related documents they identified.

This tremendous effort not only made key materials freely available online but also helped researchers from a variety of backgrounds read and understand the often challenging documents. It supported and was bolstered by descendants’ and students’ organizing efforts. In 2017, in response to pressure from descendants, Georgetown and the Jesuits offered a formal apology—in the form of a Liturgy of Remembrance, Contrition, and Hope—for their role in slaveholding and the 1838 sale. Undergraduates engaged in summer research projects using library materials, helping to fill out a timeline of Jesuit slaveholding and learning more about the Black Catholic communities that remained in southern Maryland after the sale. Students even led a referendum campaign to establish a fee of $27.20 per semester to benefit descendants; although 66 percent of students voted in favor, the university has not agreed to implement it.

The Georgetown Slavery Archive was a first, major step toward increasing accessibility to the archival legacy of slavery at Georgetown. But if the Jesuits and the university were to truly commit themselves to making this history accessible, the archival collection itself needed to be revamped. As both regular users and library staff were keen to point out, many found that the online finding aid for the Maryland Province Archives was impenetrable. Worse, it obscured the history of enslavement, with materials’ descriptions focused on powerful white Jesuits, and key documents pertaining to slavery were sometimes not noted at all.

In 2018, the Jesuits of the Maryland Province and Georgetown University committed to hiring an archivist and a digital production coordinator to overhaul the arrangement of the collection, create a new finding aid, and digitize the majority of its contents. While the goal was to make the entirety of the collection more accessible, the main objective was to amplify information about slavery. In 2019, Mary Beth Corrigan, curator of Collections on Slavery, Memory, and Reconciliation, devised a new arrangement that would divide materials based on the Jesuit administrative structure—a logical approach to organizing a vast and often bureaucratic collection. Later that year, I became the archivist for the Maryland Province Archives; my task was to rearrange materials and create a new online finding aid that clearly identified materials pertaining to slavery. Theodore Mallison began as the project’s digital production coordinator, overseeing one of the largest digitization initiatives the library had undertaken.

Several developments have since bolstered the project. First, as other universities have begun examining their institutional ties to slavery, there is a broad recognition of the necessity of making related archives more accessible. Second, the Society of Jesus itself has become increasingly open to examining its deep ties to slavery and has acknowledged that archives are paramount to fostering dialogue with descendants of enslaved individuals. Finally, thanks to a growing call for inclusive description of materials, libraries and archives are more aware of the significance and power of the language used in catalogs and finding aids. All of this has led to greater support for our work to better organize, describe, and make accessible the Maryland Province Archives—and also greater interest from a public that is now more aware that universities participated, directly and indirectly, in the institution of slavery.

The new finding aid now features a more logical organizational structure, and high-resolution digital images are linked directly to folder descriptions. Relevant folders are flagged as containing “materials on slavery” and are accompanied by descriptions of their contents. Users are informed that, despite efforts to make the finding aid more inclusive, they may still encounter problematic language or inadequate descriptions, and that we welcome feedback that will make our collection more transparent and accessible for all.

We must recognize that the sources to which we guide users will always be reevaluated, reinterpreted, and reframed.

Once digitization is complete, the Maryland Province Archives, and the history of slavery that it reveals, will be more accessible to a wide range of users—to students, scholars, and especially descendants of the enslaved. Georgetown’s archival work is part of a growing movement among universities with ties to slavery, many of which have launched complementary archival projects. Georgetown is part of On These Grounds, a multi-institution digital humanities project using archival documents to create an ontology to describe the lived experiences of enslaved individuals. And almost one hundred universities across the United States, Canada, Colombia, and the United Kingdom are now part of the Universities Studying Slavery consortium, which fosters collaboration and exchange with slavery, memory, and reconciliation initiatives.

Despite these developments, however, our work at the Maryland Province Archives is far from done. As the project’s archivist, I hope that the finding aid will not be static, but will function as a living document that can continually be improved to better meet the needs of those for whom the collection’s history is personal. For those of us engaged in archival work related to universities and slavery, we must recognize that the sources to which we guide users will always be reevaluated, reinterpreted, and reframed. How we contextualize our archives must be similarly open to change and improvement. If we truly wish to contribute to memory and reconciliation efforts—if we take seriously the mandate to make the history of slavery accessible to those whose lives it impacted the most—then we must be willing to accept that this work will never really be finished.

Cassandra Berman is archivist for the Maryland Province Archives at Georgetown University. She tweets @BermanCassandra.

Source: American Historical Association