The discussions between the two delegations were not easy. This was not surprising in light of the difficult topic and the fact that only seven years had passed since the liberation of the concentration camps and the end of WWII. Most of the population in West Germany opposed the reparations. The German public mainly was against the large sum that Chancellor Adenauer was prepared to accept as a starting point of the negotiations, some four billion German marks. However, Adenauer understood well that there was no alternative to reaching a compromise with the Israeli side, in order to restore West Germany to its proper standing among the nations of the world. In contrast, every claim against the East German government remained unanswered since the Communist regime, which obeyed instructions from Moscow, never recognized the responsibility of the entire German people for the Holocaust and the atrocities committed in its name until 1945.

Even before the negotiation between representatives of both countries (Felix Shinnar from the Israeli side and Franz Böhm from the German side) claims were submitted against formal entities in Germany. The claims were submitted at the level of various states within Germany that later comprised the Federal Republic – but there was no overarching German arrangement with clear objectives and sums.

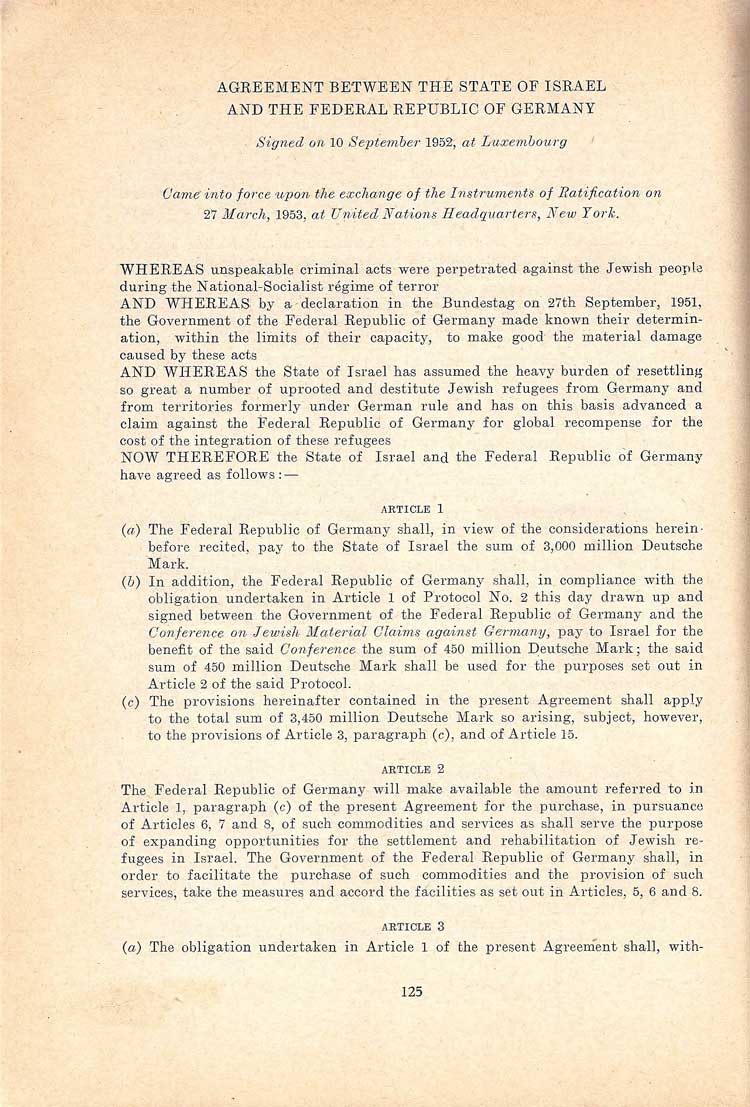

The negotiations between the countries were long and difficult. Many discussions were held, some of which conducted under a veil of secrecy out of fear that the representatives would be physically harmed. In May 1952, a serious crisis occurred, and the sides left the discussions following a heated debate regarding the amount to be paid as reparation. Ultimately, towards the end of 1952, the representatives – among them, the President of the World Jewish Congress, Nahum Goldmann – reached an agreement. According to the agreement, West Germany committed to supply the State of Israel with goods and services valuing 3.5 billion marks over a period of 12 years. Part of the agreement was the German assurance to enable personal reparations too, as well as the return of property to its legal owners. In order to follow through on this agenda, an additional sum of 450 million marks was promised.

Not only did many German citizens have reservations about the agreement-in-process. Considerable portions of the Israeli public were also unprepared to accept neither the very concept of negotiations with Germany nor the funds from the “land of the murderers,” which was defined by opponents as “blood money.” Menachem Begin led the struggle against the agreement and against David Ben Gurion’s basic policy, which for years promoted rapprochement between Israel and West Germany. In the spring of 1952, when the negotiations between the two parties was already underway, Begin gave speeches at mass demonstrations organized against the reparations. Demonstrators included many Holocaust victims who had not come to terms with the contact between the Jewish State and the Germans, who only seven years earlier had been part of the Third Reich, the embodiment of evil in modern Jewish history.

The short period of time since the Holocaust, the profound shock experienced by the Jewish public on discovering its extent and results, and the signs of Germany’s quick rebound to the community of legitimate nations, aroused strong feelings and caused an uproar among the Jews in Israel and around the world. The thought that those who just yesterday had been the worst murderers of the Jews would today pay monetary compensation for an unforgivable crime was for many an intolerable prospect. A certain opposition arose also to the idea that the young State of Israel was taking on itself to represent the Jews as a whole and was agreeing in their name to accept monetary compensation from the Germans. The matter was so sensitive that the state authorities preferred to speak of “reparations,” relying on a little used Hebrew term, shilumim, which stresses payment and avoids describing the nature of the payment. The term replaced the problematic concept of “compensation,” in order to avoid creating the impression that the state believed that it was possible to compensate survivors and offspring of the victims for what the Nazis had done to them.

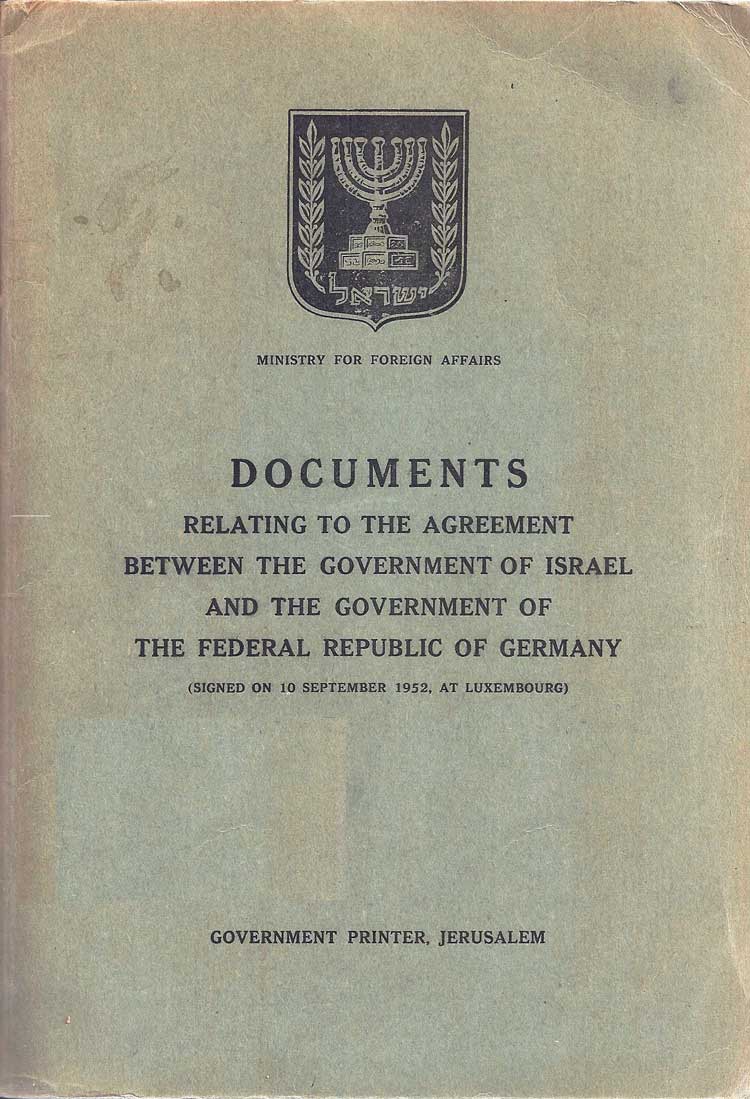

On September 10, 1952, the representatives signed the agreement. The signing took place at a neutral location: at the town hall of Luxembourg. Moshe Sharett, as the Israeli Foreign Minister, Nahum Goldmann, representing the Jewish Agency, and Konrad Adenauer, as presiding Foreign Minister (together with his role as Chancellor of the Federal Republic). Today, most historians agree that it is thanks to Adenauer that the agreement received political support in Germany, support which had not existed during the various stages of contacts made to pave the way to the agreement. His sincere understanding that there was no doubt regarding the responsibility of modern Germany for Nazi crimes shaped one of the basic guidelines of German policy to this day. Indeed, Germany’s recognition of its responsibility for Nazi crimes and the special relationship with the State of Israel rooted in it are foundation stones in the relations between two countries, regardless of the makeup of the governments of Germany and Israel.

As part of the reparations, many goods reached Israel which helped the state economy to stabilize over the years. For example, Israel received new-fangled German-manufactured trains, which were operated for a number of years by the Israel Railways. However, it quickly became apparent that the delicate motors could not withstand the climatic conditions of the Middle East, so that the trains were removed from service. Some of the cars enjoyed a surprising second career: one was donated to the medical non-profit “Yad Sarah,” and served as the organization’s office in Jerusalem. Another car serves today as a home for the “HaKaron” [“the train-car”] puppet theater, located in the Liberty Bell Garden in Jerusalem.

Article source: The National Library of Isreal