In the 20th century, the country issued reparations for Japanese American internment, Native land seizures, massacres and police brutality. Will slavery be next?

The papers were handed out one by one to the elderly recipients—most frail, some in wheelchairs. To some, it may have looked like a run-of-the-mill governmental ceremony with the usual federal fanfare. But to Norman Mineta, a California congressman and future Secretary of Transportation, the 1990 event was deeply symbolic.

The papers were checks for $20,000, accompanied by a letter of apology for the internment of over 120,000 Japanese Americans during World War II. They were the first issued under the Civil Liberties Act of 1988, a historic law that offered monetary redress to over 80,000 people.

Mineta had spearheaded the law, fighting for a government apology and financial redress for nearly a decade. As he watched, he flashed back to his own internment during the war, first at a racetrack, then at Heart Mountain War Relocation Center in Wyoming. His family had been forced to leave their home and business behind.

Now, Mineta felt, the government had finally begun the process of reconciliation. “The country made a mistake, and admitted it was wrong,” he says. “It offered an apology and a redress payment. To me, the beauty and strength of this country is that it is able to admit wrong and issue redress.”

Today, the law is remembered as the most successful push for reparations for a historic wrong in U.S. history. But the United States’ track record of reparations and official apologies is scattershot—and it has yet to tackle one of its most glaring injustices—the enslavement of African Americans. Many argue that slavery in America has legacies that continue to shape society today.

Though demands for apologies and financial restitution are not new, reparations for a state’s behavior toward its citizens are relatively modern. The idea of a state apologizing for, much less paying for, its actions toward its own citizens was almost unthinkable until Nazi Germany orchestrated a large-scale genocide. About 6 million Jews were murdered during the Holocaust, and for the first time the world grappled with how to make a nation pay money to atone for a historical injustice.

“There was the sense that Germans had done something very bad and needed to make amends,” says historian John Torpey, a professor at The Graduate Center of the City University of New York, and the author of Making Whole What Has Been Smashed: On Reparations Politics. “That was the price of admission for a return to the community of civilized nations.” Germany has since paid hundreds of millions of dollars to Israel, individual Holocaust survivors, and others.

Since then, the United States has followed suit. But though it has paid reparations to some groups it wronged through unjust treaties, coups and brutal experiments, others who still contend with the ramifications of historic injustices continue to wait for compensation.

Native American Reparations: Belated Payment for Unjustly Seized Land

President Harry S. Truman signing a bill providing for the establishment of the Indian Claims Commission. (Thomas D. Mcavoy/The LIFE Picture Collection, Getty Images)

World War II sparked a movement to address one of the United States’ historic wrongs: its treatment of Native Americans over centuries of conquest and colonization. Native Americans enlisted in World War II in disproportionately high numbers: 44,000, or nearly 13 percent of the entire population of Native Americans at the time, served as code talkers who stumped the enemy with their tribal languages and brave service members who fought in the European and Pacific theaters of war. After World War II, momentum to compensate tribes for the unjust seizure of their lands grew.

In 1946, Congress created the Indian Claims Commission, a body designed to hear historic grievances and compensate tribes for lost territories. It commissioned extensive historical research and ended up awarding about $1.3 billion to 176 tribes and bands. The money was largely given to groups, which then distributed the money among their members. For some tribes whose members didn’t live on a reservation, note historians Michael Lieder and Jake Page, the money was distributed per capita. For those who did live on reservations, the money was often earmarked for tribal projects.

However, the actual funds only averaged out to about $1,000 per person of Native American ancestry, and most of the money was put in trust accounts held by the United States government, which has been accused of mismanagement over the years. “Gambling has had a more positive impact on the quality of life on reservations than did the Indian Claims Commission Act,” Lieder and Page write.

And it took decades for a formal apology. Tucked inside a defense spending bill, the United States apologized for what it characterized as the “many instances of violence, maltreatment, and neglect inflicted on Native Peoples by citizens of the United States” in 2009.

Native Hawaiian Reparations: Land Leases for the Overthrow of a Kingdom

A portrait of Lili’uokalani, who was the Queen of Hawaii, in Honolulu, 1917. (Underwood Archives, Getty Images)

Beginning in 1893, Native Hawaiians’ extensive land holdings were taken by the federal government in the wake of its overthrow of the Kingdom of Hawai’i. The loss of lands had actually begun earlier: As white businesses flocked to Hawaii in the late 19th century, they bought up huge swaths of land and established plantations. As low-paid workers flocked to the island, Native Hawaiians began living in crowded cities and dying of diseases for which they had no immunities.

As a result, Native Hawaiians nearly died out. In 1920, there were an estimated 22,600 Native Hawaiians left, compared to nearly 690,000 in 1778, when Europeans first made contact with the islands.

In 1917, lands leased from Native Hawaiians by large sugar and ranching companies began to come up for renewal. John Wise, a Native Hawaiian who was the territory’s Senator, joined with Jonah Kūhiō Kalanianaʻole, a prince before the United States seized Hawaii, to argue that those lands should be set aside for Native Hawaiians.

The Hawaiian Homes Commission Act of 1920 established a land trust for Native Hawaiians and allowed people of one half Hawaiian ancestry by blood to lease homesteads from the federal government for 99 years at a time for a total of $1.

“Although the act was seen as helping a declining race,” writes historian J. Kehaulani Kauanui, “it was sharply limited in its potential for rehabilitating Hawaiians.”

Much of the land was remote and unfit for development, and it put people who married non-Native Hawaiians at risk of losing their land. Today, those problems persist. Though the Native Hawaiian population has surged, there remains a long waiting list for homestead lands, and families that inherit homesteads must prove their 50 percent Hawaiian descent to keep them. The United States only apologized for its treatment of Native Hawaiians in 1993, a century after the overthrow.

Tuskegee Experiment Reparations: Compensation for Medical Brutality

Participants in the Tuskegee syphilis experiments. (The National Archives)

In some cases, federal and state governments have made payments to people harmed by brutality. In 1973, for example, the U.S. began an attempt at reconciliation for the Tuskegee Experiments, in which 600 black men were unknowingly left untreated for syphilis after being misled by officials who involuntarily enrolled them in a “treatment program.”

The existence of the experiment, and its horrifying extent, only became clear after Jean Heller, an investigative reporter for the Associated Press, wrote a story on the study and its effects. After a class-action lawsuit, the men were awarded $10 million and the United States promised to provide healthcare and burial services for the men. Eventually, the state ended up awarding healthcare and other services to the men’s spouses and descendants, too.

It took decades, though, for a presidential apology for the Tuskegee Experiment. In 1997, President Clinton called its victims “hundreds of men betrayed” and apologized on behalf of the United States. But financial compensation was cold comfort to more than the study’s victims. Decades later, the experiment is correlated with increases in mistrust of the medical establishment, overall mortality and reluctance to see medical providers among black men, who face significant health disparities compared to their white counterparts in the United States. “No scientific experiment inflicted more damage on the collective psyche of black Americans than the Tuskegee Study,” writes historian James H. Jones.

Cities and states, rather than the federal government, have led the way in financial compensation for most other cases of brutality. Take Florida, where lawmakers passed a bill that paid $2.1 million in reparations to survivors of the Rosewood Massacre, a 1923 incident in which a majority-black Florida town was destroyed by racist mobs. Or Chicago, which created a $5.5 million reparations fund for survivors of police brutality aimed at black men during the 1970s and 1980s.

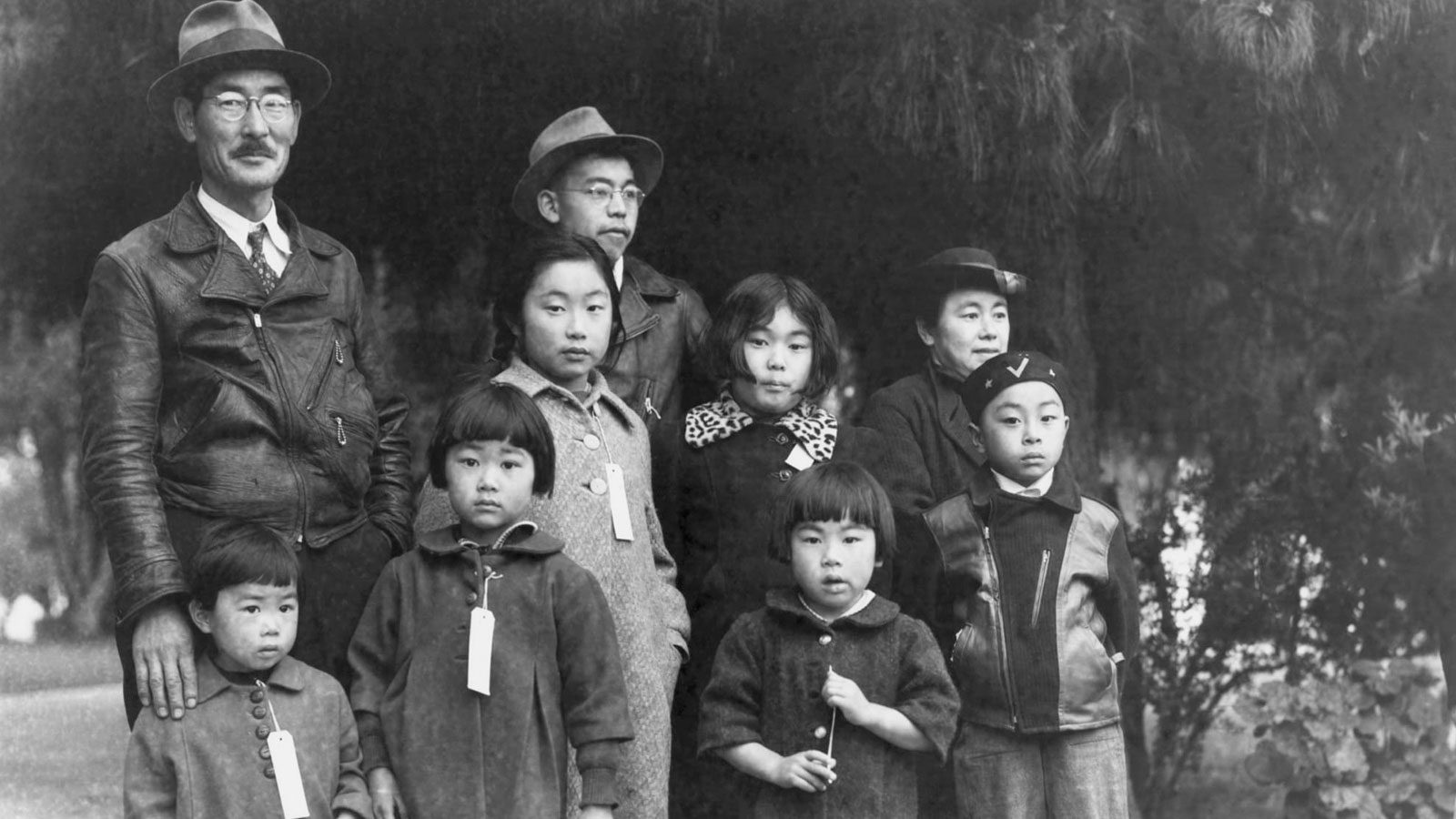

People of Japanese Descent: Reparations for Internment During World War II

Members of the Mochida family in Hayward, California, wait for bus that will take them to an internment camp at the start of World War II. (National Archives)

The Civil Liberties Act of 1988 Congressman Mineta spearheaded was a watershed moment for survivors of historical injustices. Though the United States did allow internees to file claims for damages or property loss after World War II, it had never paid reparations. That changed after the bill, which apologized for Japanese American internment and granted $20,000 to every survivor.

But despite strong grassroots support at the outset for the bill, notes Mineta, officials were wary of paying survivors. They opposed the bill despite the recommendations of a government-appointed commission that considered testimony from over 750 witnesses and concluded that internment was the result of “race prejudice, war hysteria, and a failure of political leadership,” not military necessity.

“So very few people even knew about the evacuation and internment,” says Mineta. When he appealed for action, his fellow lawmakers would ask “This happened over 40 years ago. Why should we keep talking about it?”

In response, Mineta asked if they would willingly confine themselves behind bars for the duration of World War II for any amount of money. “Most people would say absolutely not,” he recalls.

After nearly a decade of Congressional roadblocks, the bill finally passed. Ronald Reagan agreed to sign the law after being reminded of a wartime speech he had given in recognition of Kazuo Masuda, a Japanese American war hero.

Will The U.S. Ever Pay Reparations for Slavery?

Iron shackles used on enslaved people prior to 1860.

Despite the success of the Civil Liberties Act of 1988, however, the United States has yet to tackle reparations for another glaring injustice: the enslavement of Africans from the earliest days of colonization to the passage of the 13th Amendment in 1865, and the long period of economic inequality and civil rights violations that followed. Though the U.S. apologized for slavery and segregation in 2009, it has never issued redress to the descendants of enslaved people.

When it comes to slavery the United States has proven unwilling to grapple with the enormity of its injustice, and of those that followed during Jim Crow segregation and the financial and social inequality faced by black Americans. In a recent Pew Research Center survey, most Americans said that slavery’s legacy still affects black Americans to this day. But that understanding has not yet fueled an overwhelming public demand for reparations.

“The politics of it are incredibly difficult,” says Torpey. He predicts calls for reparations for slavery will only gain footing in the wake of a commission similar to the one that helped get the Civil Liberties Act of 1988 off the ground. In June 2019, the House Judiciary Committee heard testimony on H.R. 40, a bill that would do just that. During the hearing, author Ta-Nehisi Coates pointed to the nation’s unjust past—and reparations as a way forward.

“It is impossible to imagine America without the inheritance of slavery,” he told lawmakers. “The matter of reparations is one of making amends and direct redress, but it is also a question of citizenship. In H.R. 40, this body has a chance to both make good on its 2009 apology for enslavement, and reject fair-weather patriotism, to say that this nation is both its credits and debits. That if Thomas Jefferson matters, so does Sally Hemings. That if D-Day matters, so does Black Wall Street. That if Valley Forge matters, so does Fort Pillow. Because the question really is not whether we’ll be tied to the somethings of our past, but whether we are courageous enough to be tied to the whole of them.”

Source: History

Featured Image: An enslaved African American family or families pose on the plantation of Dr. William F. Gaines in Hanover County, Virginia, 1862.