Turbulent history … Tamara Lawrance in the BBC adaptation of Andrea Levy’s The Long Song. Photograph: Heyday Television/Carlos Rodriguez

From prize-winners Esi Edugyan and Marlon James to debut novelists such as Sara Collins, a new generation of novelists is exploring a painful past.

By Colin Grant, The Guardian —

Two hundred years ago, slave narratives seemed one of the few routes to publication for black writers on both sides of the Atlantic. Autobiographical accounts written by former slaves such as Olaudah Equiano, Harriet Jacobs and Frederick Douglass proved enormously popular with readers, who were captivated by their gothic horror and the possibility of redemption. Their stories of escape were frequently as inspiring as they were unfathomable. How could Jacobs have hidden for several years in an attic room whose ceiling was so low that she could never stand up? Did Henry “Box” Brown have second thoughts before he sealed himself inside a wooden crate and had it mailed to Quakers in Philadelphia?

Novels based on slave testimonies, such as Toni Morrison’s Beloved and Fred D’Aguiar’s The Longest Memory, later superseded the hundreds of true-life stories. And though the fictions of black writers are rich and varied today, those descended from the enslaved are increasingly drawing on their history, to great acclaim. Recent debuts, including Yvonne Battle-Felton’s Remembered, longlisted for this year’s Women’s prize for fiction (and reviewed on page 27), and Sara Collins’s The Confessions of Frannie Langton,a historical novel published early next month, set partly in pre-emancipation Jamaica, have taken slavery as their central theme. “Whether I liked it or not the idea of slavery stuck like a bur,” says Collins. “It was a kind of obsession that needed to be exorcised.”

Urgent voices … clockwise from top left: Esi Edugyan, Marlon James, Colson Whitehead and Sara Collins. Photograph: REX Shutterstock/Mike McGregor/Getty Images/ Sophia Evans

These first-time writers join a formidable list of recent prize-winning novelists including Marlon James, Esi Edugyan, Jesmyn Ward and Colson Whitehead. After 400 years of blood-soaked history, it seems that the trauma of slavery lies just beneath the surface of contemporary life.

What comes across in all of the writing on the Atlantic slave trade is the sustained tension between a determination to close the chapter on slavery and the desperate fear of forgetting. In D’Aguiar’s The Longest Memory (1994) the elderly slave Whitechapel inadvertently betrays his runaway son, who is captured, whipped and dies. At the start of the novel, Whitechapel pleads to the reader: “Don’t make me remember. I forget as hard as I can.”

Whitechapel’s dilemma is one that resonates with many black people, myself included, who feel ambivalent about the depiction of slavery; there’s a reluctance to revisit and be continually associated with its tortured past. Can’t we just move on? Not yet, argue authors such as Battle-Felton, who sees Remembered “as a form of advocacy”. “We’re still living that painful consequence of slavery and are daily touched by its racism. I was aware when writing the book that black people were being killed by police at an alarming rate in the US, that the narrative hadn’t changed.”

Out at sea, Shabine, the protagonist in Derek Walcott’s narrative poem “The Schooner Flight” (1979), is struck by an otherworldly vision as his vessel floats through “a rustling forest of ships”. They are slave ships with the flags of every nation, and Shabine laments: “Our fathers below deck too deep, I suppose, / to hear us shouting. So we stop shouting. Who knows / who his grandfather is, much less his name?”

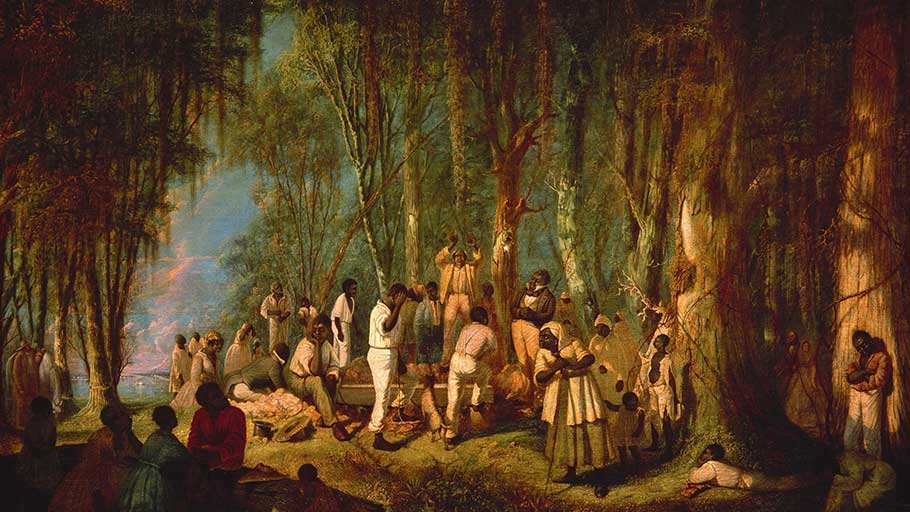

Plantation Burial by John Antrobus. Photograph: Historic Images/Alamy Stock Photo/Alamy Stock Photo

After four novels, the late Andrea Levy might have felt she’d given slavery the slip. She had hesitated to write about the subject, doubting whether she would “be able to stomach it” especially as she “didn’t want to write a misery fest”. Yet her fifth and final novel, The Long Song(2010), straddles the turbulent end of the slave system and the fragile early years following emancipation. It was adapted by the BBC and screened shortly before her death last month. It was her belief that “Britain at its peril, really, disregards what happened in the Caribbean”. The Long Song has inspired others to speed our country’s sluggish reckoning with its slave past.

While slavery was woven into the fabric of society in the US, especially in the south, the visceral fact of plantation slavery was not felt in Britain. A small number of slaves did make their way to English ports, often accompanying their masters. They would often part ways from their owner on arrival, only to be recaptured later. In 1569 a court of law had ruled “that England has too pure an air for slaves to breathe in”, and in subsequent legal challenges it was determined that any slave arriving in England was automatically free.

At the height of the empire, for Britons who had never set foot in the colonies, the notion of slavery was likely to be mediated through books such as Harriet Beecher Stowe’s sentimental abolitionist novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin(1851). Though readers might agonise over the “peculiar institution” and mourn the death of Uncle Tom, for much of the British public, slavery happened elsewhere. British propaganda after emancipation ensured that the UK was remembered admirably for its part in abolition rather than for the plunder of Africans from the continent, for establishing an Atlantic slave trade in the first place.

Over the decades it’s been inspiring to see black female

protagonists occupy spaces previously denied them.

The nature of slave stories has altered over time. Testimonies such as Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave (1845) served a practical purpose in furthering the cause of abolition. Former slaves, mindful of the sensibilities of their readers, tempered their language. Douglass writes in his autobiography: “But let us now leave the rough usage of the field … and turn our attention to the less repulsive slave life as it existed in the home of my childhood.”

By the time Toni Morrison embarked on Beloved (1987) she was disinclined to pull punches. Her job, she wrote, was “to rip that veil drawn over ‘proceedings too terrible to relate’.” Beloved’s protagonist, Sethe, is haunted by the memory of the daughter she murdered to spare her the agonies of slavery. Morrison’s ambition was to show how “the Herculean effort to forget would be threatened by memory desperate to stay alive”.

This also appears to be a governing principle of Battle-Felton’s Remembered,in the relationship of two sisters – Spring, an elderly emancipated slave and Tempe, a tormented ghostly apparition, who died in a fire, and whose role invites comparisons with Beloved. Spring narrates the story of Remembered,spooling back and forth through time. It begins in 1910, with Spring sitting in a Philadelphia hospital room at her son’s bedside; he has been beaten by a white mob and left for dead. The spectre of the malevolent Tempe appears in the room cajoling her sister to recall their family’s terrible history while the son still lives.

Collins’s protagonist Frannie is an exceptional fair-skinned black woman, educated as an experiment in social engineering by her master, Langton. But though travel to London frees her from the shackles of slavery, Frannie’s English life is shadowed by memories of her assisting her gentleman “scientist” master and lover in his pseudoscientific experiments back in Jamaica.

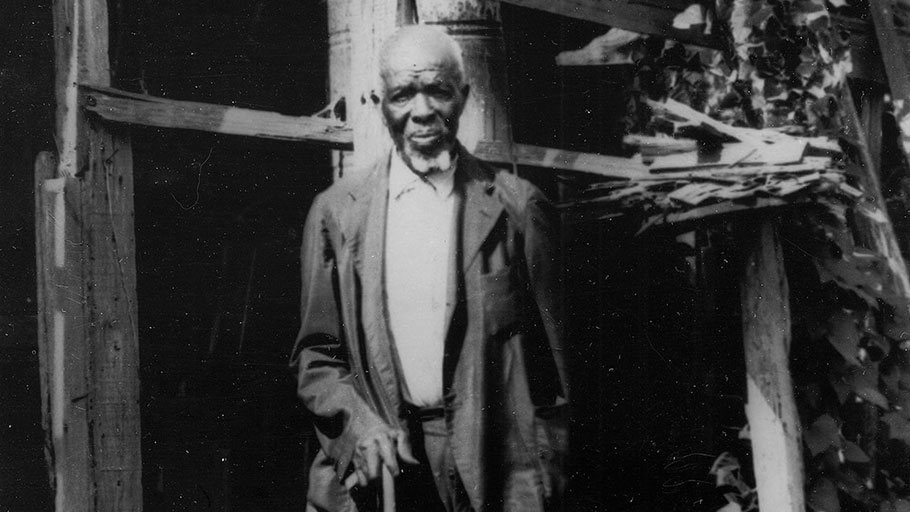

Cudjo Lewis, whose story is told in Barracoon. Photograph: Courtesy of McGill Studio Collection, The Doy Leale McCall Rare Book and Manuscript Library, University of South Alabama

Collins uses history as a way to talk about the hypocrisy of English society at that time. With an eye on Charlotte Brontë, she casts Frannie in a 19th-century gothic romance and murder mystery, asking us to imagine a world in which “Jane Eyre [now a black maid] had been given as a gift ‘to the finest mind in all of England’, and then accused of cuckolding and murdering him”. Collins’s real interest, though, lies in exposing the constraints on black characters in historical fiction, who are usually denied a love story.

We seem to have come full circle. Revealing the interior lives of slaves and demonstrating their humanity and capacity for love was at the core of early slave narratives; it certainly animated Zora Neale Hurston, whose Barracoon, a biography of Cudjo Lewis, the last slave abducted from Africa, was posthumously published last year. Hurston bemoaned that slaves had too often been barred from the discourse on slavery in American history drawn from journals, manifests, diaries and bills of sale, all written from the perspective of the beneficiaries of the slave trade: “All these words from the seller,” lamented Hurston, “but not one word from the sold.”

Hurston was also suspicious of white researchers encroaching on this “black” story, a concern that has been echoed in relation to white authors’ appropriation of slave narratives in their fiction, from the condescending portrayal of Uncle Tom (based on Josiah Henson’s narrative) to the stereotype of the slave insurrectionist in William Styron’s The Confessions of Nat Turner (1967).

It’s an old complaint that will surely surface again. Kate Morrison, a white British debut novelist, has also been inspired by Jane Eyre in her portrayal of Nsowah, the daughter of a Ghanaian princess who, along with her child, is briefly captured by Portuguese slavers before being freed and subsequently given to a Sussex merchant. A Book of Secrets is due out next month, though Morrison began the novel 15 years ago, when alerted to the lack of black protagonists in historical fiction.

Over the decades it’s been inspiring to see how writers have corrected that omission and to witness how black female protagonists from the margins of society have come to occupy spaces previously denied them. Without the fierce determination of characters such as Morrison’s Sethe and Battle-Felton’s Tempe, insisting we remember the injury and injustices of slavery, then, as Whitechapel says in The Longest Memory, “the future is just the past waiting to happen.”