Prince Charles and Camilla Duchess of Cornwall with Mia Mottley, the prime minister of Barbados, 19 March 2019. Photograph: REX/Shutterstock

Charles and Camilla are the latest to arrive and help whitewash the injustices of slavery and empire.

By Nalini Mohabir, The Guardian —

Once upon a time monarchs ruled by divine right, then later with charismatic authority. The future king Prince Charles (#NotMyPrince) has neither. Yet Caribbean governments are paying for Prince Charles and Camilla’s royal tour of the Caribbean which began on Sunday and continues for 12 days, to “celebrate the monarchy’s relationship with these Commonwealth realms”.

Charles, future head of the Commonwealth, needs this visit. But what does the Caribbean get in return? Caribbean countries are footing the majority of the bill, while he is paid to persuade us of the harmonious ties between Britain and the Caribbean. This function stems from his inherited role of embodying imperial legacy. But why should Caribbean governments facilitate this performance?

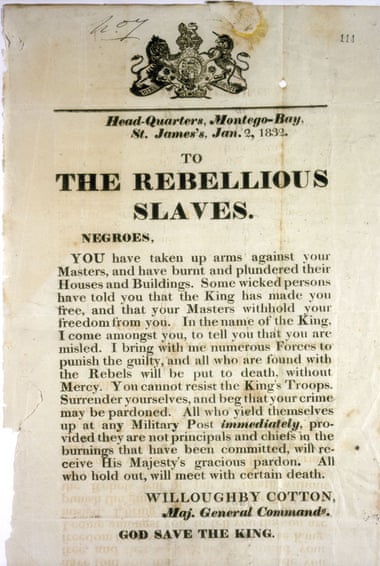

To quote the academic Paul Gilroy, “Without the crude injustices of racial slavery we are required to know even more comprehensively than in the past precisely what we are against and why.” In the not too distant past, West Indian schoolchildren were taught that Britain was the mother country and the royal family was to be revered. This identification with Britain was encouraged during the first and second world wars despite the persistent racial hierarchies of empire. For example, Jamaican soldiers on their way to the battlefront during the first world war were caught in a blizzard off the coast of Halifax. Research shows that imperial authorities denied permission to the Jamaican soldiers to come ashore. As a result, many suffered frostbite and had their limbs amputated. Despite their willingness to fight and potentially die for the crown, black Caribbean people were not recognised as equals.

Even after decolonisation, several independent countries did not sever ties with the crown, and those that did remained convinced of the benefits of voluntary association through the Commonwealth. The rituals of the royal tour in the post-colonial period exploited this notion of progressive relations between the former imperial centre and the Caribbean. Before his marriage, Prince Harry was sent to playfully promote royal celebrity in the region. In a picture with Usain Bolt, Harry mimicked Bolt’s lighting bolt pose, and Bolt allowed Harry to win a race. These photos encapsulate the purpose of the Caribbean for the royal family – to display that they have transcended the racist past and take an interest in the achievements across their “realm”, while maintaining their status at the head of the Commonwealth.

Even after decolonisation, several independent countries did not sever ties with the crown, and those that did remained convinced of the benefits of voluntary association through the Commonwealth. The rituals of the royal tour in the post-colonial period exploited this notion of progressive relations between the former imperial centre and the Caribbean. Before his marriage, Prince Harry was sent to playfully promote royal celebrity in the region. In a picture with Usain Bolt, Harry mimicked Bolt’s lighting bolt pose, and Bolt allowed Harry to win a race. These photos encapsulate the purpose of the Caribbean for the royal family – to display that they have transcended the racist past and take an interest in the achievements across their “realm”, while maintaining their status at the head of the Commonwealth.

With Harry’s marriage to Meghan Markle, some believed that the royal family had become “colour-blind”, particularly after incorporating black culture into the royal wedding at Windsor Castle. However, it is important not to mistake this as an embrace of black people (the look on the extended royal family’s faces made that clear); nor was it a turning point in the relationship of Britain to the Caribbean.

Last year’s Windrush scandal shows the callousness with which Britain treats Caribbean people, by deporting or threatening to deport senior West Indians who migrated legally when their passports marked them as subjects of the British empire. And Caribbean migrants continue to be denied the benefits of full citizenship.

Will any of the Caribbean governments hosting Prince Charles and Camilla (including St Vincent’s anti-imperialist prime minister Ralph Gonsalves) bring up the lack of respect and disregard for the region and its diaspora? Will Caribbean trade unions boycott their visit and refuse to be a colourful backdrop for an orchestrated campaign to whitewash Britain’s continuing imperial legacies? Will “unruly” activists take to the street and demand the royal family be held accountable for the past (eg by paying reparations)? Or will this be business as usual, ignoring a bloody royal legacy?

The British government supports the royal family through a sovereign grant, but this does not cover local costs for royal visits. So St Lucia will essentially be paying the former imperial power to be the guest of honour at its independence celebrations – to legitimise independence? The Barbadian government will be subsidising Charles to lay a wreath at the Cenotaph in honour of those who died during the world wars, many of whom fought as a way to demonstrate they were deserving of the elusive civil rights promised by the British empire. The prince will also attend a demonstration of hurricane preparedness in Barbados, even though the British Virgin Islands has still not been able to fully rebuild and repair its infrastructure after hurricane Irma despite being a British territory. Charles and Camilla will visit Grenada (in the same month as the 40th anniversary of the revolution) to learn about the history of cocoa; do they know cocoa is a plantation crop?

It is not only the royal family that seems eager to wash away a history of empire through a facile notion of friendship and cooperation across the Commonwealth. Islands of elites connected through their own privileges seem willing to show hospitality and welcome to the royals in exchange for a sprinkle of royal prestige. What if, instead, Caribbean countries said no to all royal tours until the Caricom reparations commission demands are met?

Nalini Mohabir teaches at Concordia University in Toronto, Canada. She is a historical geographer whose research focuses on the Caribbean