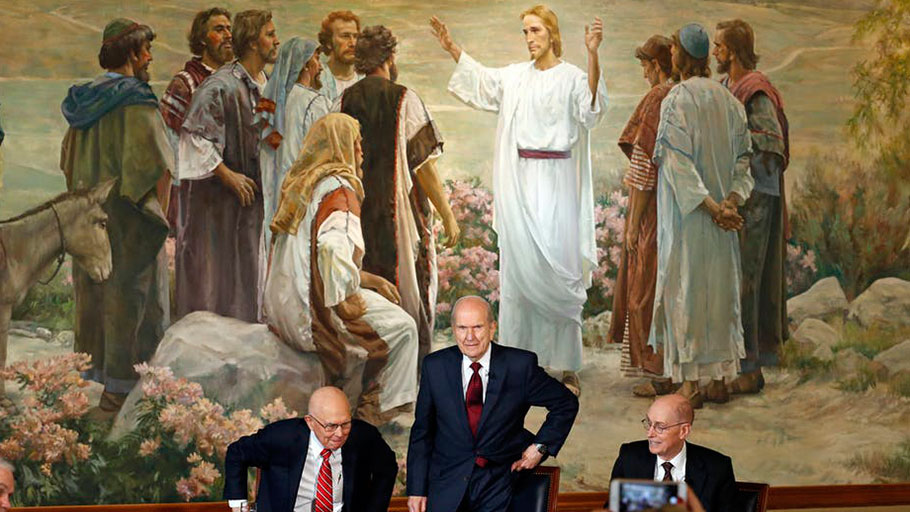

The Mormon church is still grappling with a racial past. AP Photo/Rick Bowmer, File

By Matthew Bowman, The Conversation —

On June 1 of this year, the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints – or the Mormons – will celebrate the 40th anniversary of what they believe to be a revelation from God.

This revelation to the then-President of the Church Spencer W. Kimball – which is known as “Official Declaration 2” – reversed longstanding restrictions placed on people of black African descent in the church.

As a scholar of American religion and Mormonism, I believe this history illustrates the struggle the Mormon church has had with racial diversity – something that the church leadership still grapples with today.

Early history of black priesthood and restrictions

In the Mormon church, all men above the age of 12 serve in a priestly office, which Mormons call collectively “the priesthood.” Additionally, all Mormons, men and women alike, are taught that the sacramental rituals most essential to their salvation are performed in Mormon temples.

The most important of these rituals is a ceremony called “sealing,” in which family relationships are made eternal. Though Mormons believe that virtually all humanity will enjoy some degree of heaven after death, only those in sealed relationships will enter the highest levels of heaven.

In the 1830s and 1840s, the earliest years of the church, under the leadership of founder Joseph Smith, African-American men were ordained to the priesthood and historians have identified at least one black man who participated in some temple rituals.

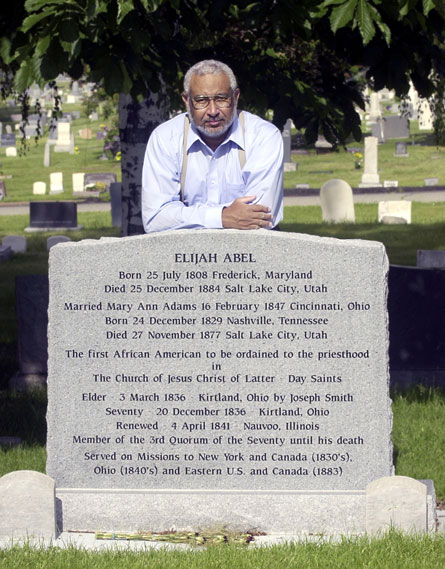

Darius Gray, a contemporary Mormon African-American leader at the tombstone of Elijah Abel. AP Photo/Douglas C. Pizac

Under Smith’s successors, however, these policies were reversed.

In 1852 Smith’s immediate successor Brigham Young announced that black men could not hold the priesthood. In the following decades, both black men and black women were barred from temple worship.

These policies affected a small number of black Mormons. A small number of enslaved black people had been brought to Utah in the 1840s and 1850s by white Mormons and some were baptized into the church. Slavery was legalized in Utah in 1852 and remained so until the Civil War. There were also free African-Americans who became Mormon. Most prominent was Elijah Abel, a carpenter who joined the church in 1832 and was ordained to priesthood office. He served several missions before his death in 1884. Jane Manning James was a free black woman who became a Mormon in 1841 and followed Brigham Young to Utah. Historians have found records of both Elijah Abel and Jane Manning James requesting permission to be sealed in Mormon temples. Both requests were denied.

More generally, after these restrictions came into place, Mormon missionaries avoided proselytizing people of African descent.

Justifications for the restriction

Young and other Mormon leaders offered various explanations for these decisions. Young, for example, repeated a long-standing folk belief that black people were descended from Cain, a Biblical figure God cursed for murdering his brother.

Historical evidence indicates that Young and his colleagues were distressed when black members of the church sought to marry white women. Young seems to have believed that barring black men from the priesthood and both black men and women from the ritual of sealing would prevent racial intermarriage in the church.

In the years that followed, other Mormon leaders offered other explanations for the restriction. Some said that black people possessed less righteous souls than white people did. Other Mormons as recently as 2012 suggested that black people had to mature spiritually before they could be allowed full participation in the church.

As a result, Mormonism historically attracted few black converts.

Global spread of Mormonism

By the mid-20th century, church membership was growing rapidly all over the world, and it became obvious that the restrictions on members of African descent were styming church growth.

In the 1940s and 1950s, Christian faiths were attracting many converts in West Africa. In Nigeria, some of these African Christians discovered Mormon publications and began writing letters to Mormon leadership requesting baptism into the church, claiming to be attracted by the church’s temple worship and teachings about heaven.

Mormon leaders in Utah were torn. As the church’s racial restrictions made it impossible to ordain African men, there could be no congregations established among black Africans. At the same time, the Nigerian government denied visas to Mormon missionaries. In the end, the church could not send missionaries or official congregations, but did dispatch Mormon literature in an attempt to guide African believers.

The spires of a Mormon temple, Johannesburg. ThisParticularGreg, CC BY-SA

The racial restrictions caused problems elsewhere in Africa as well. In South Africa, for example, converts had to document their genealogy to demonstrate a lack of African ancestry before they could receive ordination to the priesthood or worship in temples. In 1954, Church President David O. McKay issued a directive that unless converts’ appearance indicated black African ancestry, they would be allowed full participation in the church.

By the 1960s and 1970s, church missions were expanding in Latin America, particularly in Brazil. As in South Africa, Mormon missionaries were confronted with the issue of determining the ancestry of their converts in a nation where intermarriage was far more common than it was in the United States.

Pressures emerged in the United States as well. As the black freedom movement expanded in the 1960s and 1970s, criticisms of the church mounted. Through the late 1960s and early 1970s, university sports teams around the country protested or boycotted playing teams from church-owned Brigham Young University.

But the leadership of the church remained was divided over whether to end the priesthood and temple restriction entirely. It was in 1978 that the conflict was resolved when President Kimball announced he had received a revelation from God.

The legacy of the restriction today

Although the church has ended the restrictions against blacks, they have had lasting effects.

Today about one in 10 converts to Mormonism are black, but surveys report that only about 1 to 3 percent of Mormons in the United States are African-American.

Despite the changes, African-American members say they still face racial discrimination. In 2012, for example, a professor at Brigham Young University suggested that God had put the earlier ban in place because black people lacked spiritual maturity.

Today, church leaders have announced a celebration of Kimball’s revelation under the theme “Be One.” They have called for unity against “prejudice, including racism, sexism, and nationalism.” This language presents a vision of Mormonism far more inclusive than language used in the past. To some African-American members of the church, though, such celebrations seem premature given the persistent presence of racist ideas within the church.

Nonetheless, at a time when the church’s growth rates in the United States are slowing down and growth rates in the global South – particularly Africa and Latin America – are rising, the celebrations this June indicate a desire on the part of church leadership to acknowledge the value of its diversity.

Kimball’s removal of the priesthood and temple restrictions on people of color may have opened the doors to a modern church, but the decision to celebrate his declaration shows how the church is still grappling with its legacy of racial discrimination.