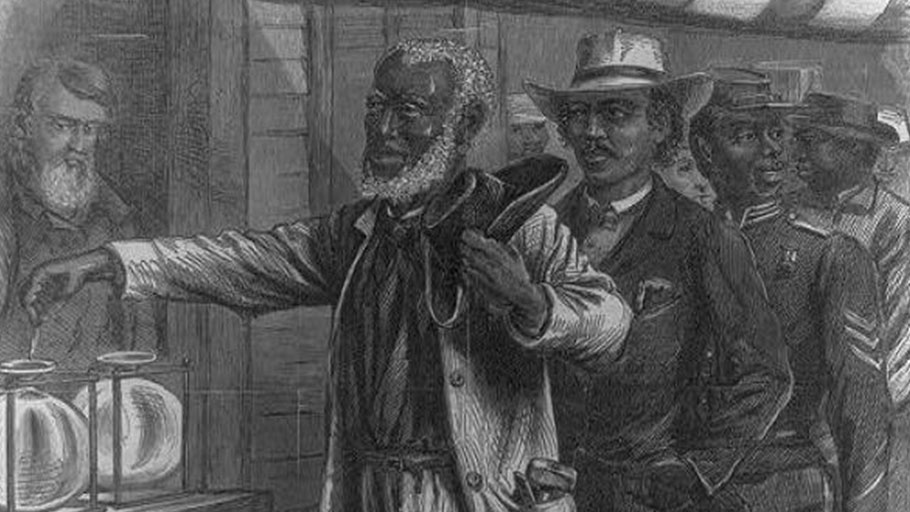

This 1867 drawing by Alfred Waud, “The First Vote,” depicts Black men waiting in line to cast ballots. In Southern states, Black men first gained the right to vote in state constitutions drafted during the post-Civil War Reconstruction era. (Drawing from the Library of Congress website.)

During the 1870s, more than a half a million Black men voted for the first time in their lives. But this wave of progressive change did not last long.

By Rebekah Barber and Billy Corriher, Facing South —

One hundred and fifty years ago, a Congress dominated by “Radical Republicans” — mostly former abolitionists who represented Northern states — mandated that Southern states rewrite their constitutions, ratify the 14th amendment, and grant Black men the right to vote in order to gain reentry into the Union. During this period of Radical Reconstruction, people who were enslaved only a few years prior took on prominent roles in reshaping their state governments.

Across the South, new Black political leaders rose up and served as delegates during their respective constitutional conventions. For instance, in North Carolina, Abraham Galloway — a formerly enslaved man from the eastern part of the state — was among the 13 Black delegates at his state’s convention who advocated for progressive policies like equal education and women’s rights to vote.

Most of the delegates were white Republicans who had opposed secession. According to Eric Foner’s book “Reconstruction,” they were mostly “upcountry farmers and small-town merchants, artisans, and professionals, few of whom had ever held political office.”

Historian Steven Hahn described the changes made by the conventions as “inscribing into fundamental law the enfranchisement and full civil standing of a very large social group — one making up nearly half the population and much more of the labor force, and held for over two centuries in the condition of slavery — thereby reconstructing the body politic of the South and potentially … the nation.”

In every former Confederate state, Blacks were elected to public offices. Indeed, these new state constitutions had granted them unprecedented political power. Shortly after North Carolina’s constitutional convention, Galloway was elected to the state Senate. Jonathan Clarkson Gibbs served as Florida’s first — and to date, only — Black secretary of state. In total, about 2,000 Black men held public office during Reconstruction.

During the 1870s, more than a half a million Black men voted for the first time in their lives. According to Adam Sanchez’s recent article for the Zinn Education Project titled “The Other ’68: Black Power During Reconstruction”: “By the time the new voter registration process was completed, Blacks were a majority of the registered voters in Mississippi, Alabama, Florida, Louisiana, and Georgia. In South Carolina, there were nearly two Blacks registered for every white person.”

But this wave of progressive change did not last long.

In response to rising Black political power, white supremacists employed voter intimidation tactics to keep Blacks from the polls, regained control of Southern state legislatures, and enacted what came to be known as “Jim Crow laws” that discriminated against Blacks and disqualified them from registering to vote. While poll taxes required voters to pay to register to vote and literacy tests forced them to interpret a passage of the constitution, so-called “grandfather clauses”exempted whites from such requirements.

As part of the backlash against Black progress, legislators also banned people with felony convictions from voting — policies that continue to disproportionately impact Black people today.

In Mississippi, for example, where voters elected two Black U.S. senators and a plethora of Black state officials during Reconstruction, about 47,000 people — a disproportionate number of whom are Black — were convicted of crimes that disenfranchised them for life just between 1994 and 2017. Although convicted felons can regain their right to vote in the state if they receive permission from the governor and two-thirds of the legislature, only 14 people did so between 2013 and 2017. Currently, there are two federal lawsuits challenging this discriminatory system.

Thwarting change in Florida

At midnight on Feb. 10, 1868, a group of moderate and conservative delegates to the Florida constitutional convention kidnapped two sleeping Radical Republican delegates and dragged them to the Tallahassee convention hall, where they helped establish a quorum to rewrite the constitution. About a week later, federal soldiers barred all of the Radical Republican delegates from entering the convention hall at all. According to historian Thomas DiBacco, federal troops did so because then-President Andrew Johnson had “urged conciliation and getting the deed done.”

Florida’s conservatives feared that if the Radical Republicans could fairly participate, they would not just meet the minimum requirements for reentry into the Union but would write a truly transformative document. In fact, before the midnight coup, the Radical Republicans — about one-third of whom were formerly enslaved Black men — had already drafted a constitution that was likely to pass since their party held the majority.

But because of the conservatives’ dirty tricks, Florida passed a constitution that permitted ex-Confederates to hold state office without taking a loyalty pledge to the United States. It also authorized the legislature to create an educational requirement for voting, diluted the power of the Black vote by giving all counties equal legislative representation, and made the state’s felon disenfranchisement law even more far-reaching. One conservative state legislator bragged that these provisions had “kept Florida from becoming niggerized.”

Today, Florida still has the strictest felony disenfranchisement law in the country, and nearly a quarter of its Black population is denied the freedom to vote. The governor and his cabinet have unfettered discretion to grant or deny the restoration of voting rights, and the current governor requires potential voters to wait five years after completing their sentences to even petition the state for the restoration of their voting rights.

So many people are now disenfranchised in Florida that some voting rights advocates suspect that their votes could have changed the outcome of the 2000 presidential election. But this November, in the wake of a federal judge’s ruling that Florida’s system of disenfranchising felons is unconstitutional, voters will get to weigh in on Amendment 4, a ballot initiative that would repeal their state’s harsh and discriminatory disenfranchisement law.

Andrew Gillum, the Democratic mayor of Tallahassee and now Florida’s first Black nominee for governor, has voiced his support for Amendment 4. “Floridians who have paid their debts deserve a second chance,” he said. “Our current system for rights restoration is a relic of Jim Crow that we should end for good.”

Southern constitutions today

While the Jim Crow era wiped out much of the progress of Reconstruction, many provisions of the Reconstructions constitutions have survived, such as the right to vote and the right to an equal education. But state legislatures continue to undermine these rights today.

In North Carolina, for example, legislators passed a sweeping voting law in 2013 that a federal court found targeted African Americans “with almost surgical precision.” The court concluded that legislators had sought out data on voting practices by race and then added provisions to the law that they knew would disproportionately impact Black voters, including a strict voter ID requirement and cuts to early voting. The court struck down the law for violating the federal Voting Rights Act and the equal protection clause of the U.S. Constitution’s 14th Amendment.

More recently, the North Carolina legislature approved a series of constitutional amendments to appear on ballots this November. One of them would require the state legislature to create a new voter ID law, while another would give the legislature power to choose the entire state elections board, which is currently appointed by the governor.

Should the amendments pass, the resulting laws could still be challenged in court. But if President Trump’s pending Supreme Court nominee is confirmed, voters are likely to find less protection for their rights in federal court. They could instead look to state courts and state constitutions to block voter suppression. After all, the North Carolina Constitution has said since 1868 that “all elections ought to be free.”

(This is the first in a series on the legacy of progressive Southern constitutions that were rewritten during Radical Reconstruction.)

Rebekah is a researcher and writer at Facing South/Institute for Southern Studies focusing on racial justice, democracy and Southern history. As a student activist she organized around issues including voting rights, the Fight for $15 and Medicaid expansion. She holds bachelor’s degrees in English and history from N.C. Central University in Durham, North Carolina.

Billy is a senior researcher with Facing South who specializes in judicial selection, voting rights, and the courts in North Carolina.