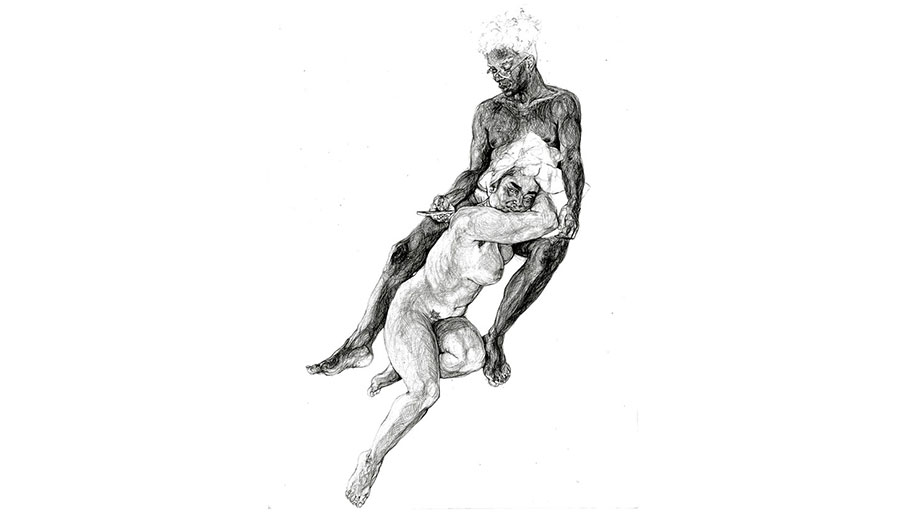

Illustration by azzeazy

Just as sleep deprivation was used as a means to control slaves, the modern-day “sleep gap” weighs down many Black people today.

What happens to a dream deferred? Does it dry up like a raisin in the sun? Or fester like a sore…” asks Langston Hughes in the haunting lines of his poem, “Harlem.” Written nearly 70 years ago, Hughes’ words remain just as relevant as ever.

“Harlem” is typically read as referring to Black aspirations—the crushing of dreams, and particularly, the promise of racial equality by American society at large. However, his words here may apply to literal Black dreams as well. A growing amount of research has found that Black Americans experience significantly less slow-wave sleep—the kind required for actual, rejuvenating rest—than white Americans. The lack of slow-wave sleep can cause serious mental and physical health issues, including premature death. This disparity, or “sleep gap,” has been the subject of numerous studies, some of which have found that Black Americans are five times more likely than white Americans to get less than six hours of sleep per night, are more likely than white Americans to feel sleepy during the day, and on average get an hour less sleep per night than white Americans.

There’s no scientific consensus on what, specifically, causes the sleep gap. As reported by The Atlantic in 2015, however, leading theories point to both experiences of discrimination and structural inequality—aspects of one’s environment that make one feel unsafe and insecure—as root causes. As Benjamin Reiss pointed out in the LA Timesin 2017, Black Americans have lacked access to sufficient sleeping environments since slavery: “Aboard the ships of the transatlantic slave trade, African captives were made to sleep en masse in the hold, often while chained together. Once in the New World, enslaved people were usually still made to sleep in tight quarters, sometimes on the bare floor, and they struggled to snatch any sleep at all while chained together in the coffle. Slaveholders systematically disallowed privacy as they attempted round-the-clock surveillance, and enslaved women were especially susceptible at night to sexual assault from white men.”

Just as sleep deprivation was used as a means to control slaves, the modern-day sleep gap continues to weigh down many Black people, like me, today. I can feel it in me: It breaks my spirit, as I exist in between half-conscious states; never fully awake or asleep, never able to distinguish between the two. This may be the true power of racism—its force encompasses everything, seeping into our dreams at night and deflating our capacity to envision a better future. How can the radical Black imagination rebel against a system that so thoroughly seeks to destroy us? What would a future look like where we are liberated, reparations are paid, and we can finally rest?

Last year, I attended an exhibition called Black Power Naps that begins to answer those questions. After debuting at Matadero Madrid Contemporary Art Center in Spain, where I saw it, the exhibition has since travelled to Performance Space New York, where it is on view through January, 2019. The ongoing project by Black Latinx artists Fannie Sosa (referred to as Sosa) and niv Acosta presents a series of interactive installations that invite Black visitors to lie, nap, relax, and play, providing “deliberate energetic repair,” as the artists put it, on the dime of white cultural institutions.

Illustration by azzeazy.

I and many other Black people are constantly aware of our Blackness in hyper-white environments, including art institutions. Elijah Anderson, a prominent ethnographer and Yale lecturer, describes us as “black interlopers” in his 2015 essay, “The White Space”: “When present in the white space, blacks reflexively note the proportion of whites to blacks…and… may adjust their comfort level accordingly; when judging a setting as too white, they can feel uneasy and consider it to be informally ‘off limits.’” As W. E. B. Du Bois suggests, we experience double consciousness, where we simultaneously become aware of both our Blackness, and the responses to it, in white spaces. The surveillance our bodies experience in art institutions—from being followed around in their gift shops to being watched by the gaze of their gallery attendants, and all amidst an undiverse collection of artworks and workforce—informs our feelings of exclusion. But perhaps Black Power Naps does something different: It is designed with Black people in mind, inverting a white art institution into a “Black space,” where the Black body is the center around which all the show’s installations conceptually orbit.

To enter Black Power Naps, you must take off your shoes. Removing one’s shoes is an act associated with sacred places—a symbolic gesture of leaving the world’s toxicity behind. Once inside the room, you see six “healing stations” before you, each “invented,” as the artists put it, to evoke different bodily sensations through physical contact. Each is adorned with silks, satins, and chiffons in delicate pastel hues to create a cozy cocoon of a room. The stations include the “Black Bean Bed,” a pool filled with uncooked black beans, designed to soothe someone experiencing a panic attack. If you lie in the pool, the beans swallow your body while cooling the skin, enveloping you in comfort. The “Air Swing,” meanwhile, is a swing surrounded by three silent fans intended to increase the amount of oxygen you breathe in and, effectively, improve sleep. And the “Atlantic Reconciliation Station” is a water bed intended to help descendants of enslaved people forcibly brought through the middle passage—or pushed off ships along the way—reconcile with the ocean by reminding them that, as the artists explain, the ocean is an “adoring entity that has always had our back.”

hese stations unwind the behaviors that white cultural institutions tend to impose on visitors, training us to keep our bodies to ourselves (don’t touch the art!) and avoid others. Here, you get to touch, lie on, and be intimate with the art. The invitation challenges the respectability politics and surveillance culture informing what it means to be a Black body in an art institution—or anywhere at all. The artists describe it as “a pleasurable citizen space.” Here, the Black radical imagination is in control.

In the background of the exhibit, a recording of the artists reading science fiction texts written by Black trans women plays so softly that it’s inaudible. You can’t consciously hear it, because you are not supposed to. The soundscape is intended as subliminal messaging designed to program empathy into white visitors, the artists tell me. “It’s cataclysmic, based purely on theory and the vibration of it, and trying to find the right kind of vibration with white people,” Acosta says. Sosa adds, “It’s like a device that provokes hyper-empathy in white people, planting this neurological map that they don’t have. They’re reprogrammed to interpret reality in a different way.”

Numerous studies have shown that white Americans believe Black people experience less pain. With this attempt to close the “racial empathy gap,” white people, for once, become the spectacle—the ones being scrutinized under the Black gaze.

When visiting the exhibition in Spain (like many other European nations, Spain has yet to apologize for its role in the transatlantic slave trade), attendees were greeted with text that boldly declared the artists intention, which provided context to the installation’s purpose. I was struck by the number of white visitors who still seemed oblivious to this mission, taking selfies with the collection’s “LIBERACIóN Y REPARACIóN” LED sign.

The various apparatuses in the exhibition, framed by the language the artists use to describe them, evoke a hybrid between a Black pleasure room and a laboratory. In doing so, it calls upon and reimagines a history of Black bodies being tortured under the guise of “experimentation” (think, for instance, of theTuskegee experiments, or the story of Henrietta Lacks). These stations, too, are “experiments,” but ones rooted in facilitating reparations for Black people. They are also reminiscent of initiatives led by the Black Panther Party, whose services included free healthcare and breakfast programs for Black people; demonstrating that Black Power activism can take many forms and that Black art is inherently political.

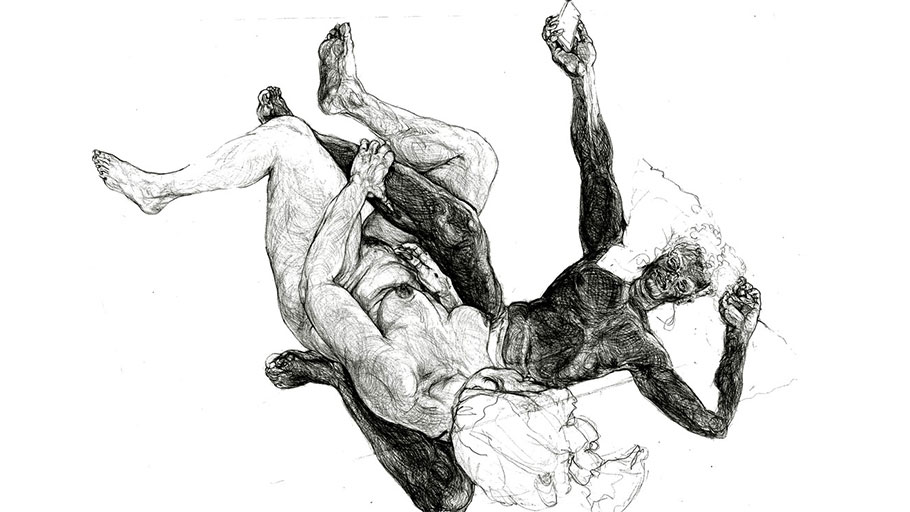

Illustration by azzeazy.

Black Power Naps complicates the idea of reparations for Black people, reminding us that reparations are not solely about money, but also time. Time is an asset in capitalism; it is, in itself, a kind of privilege that has translated into financial wealth for white people. If we reframe centuries of unpaid slave labor as sick leave, annual leave, or overtime, then we, the descendants of the enslaved, are heavily owed. We also have reason to be restless, angry, and, as Hughes predicts in “Harlem,” ready to explode. This sentiment is shared by the artists, who believe a call to action means “ front lines existing in our bedrooms as well as in the streets.”

Time, as we know it, is a colonial invention and forms the backbone of American society, making the racial distribution of time inherent to white privilege. As whiteness dictates freedom, education, pleasure, and social mobility, have you ever wondered why so many of those considered to be our “greatest” artists or philosophers are white men? Who among us has the access to time to make “masterpieces” or to “think,” without dealing with the impacts of oppression? Racism robs us of our time to be creative, to dream or simply be. In addition, Black people are both disproportionately incarcerated and expelled from schools in the United States and many other Western countries. If Black children were given the same amount of time as their white peers to remain in education, this would disrupt the “school-to-prison-pipeline,” a phenomenon that disproportionately affects Black youth. Our dreams are constantly deferred.

By inviting Black people to stop and rest, Black Power Naps begins to let us reclaim our time. And, in doing so, it restores our capacity to dream as Black people—to imagine a future of Black rest, relaxation, and idleness.

When was the last time you enabled Black people to rest?

Editor’s Note (Broadly)

As we brace for 2019 and stack up our resolutions, Broadly is focusing on finding motivation for the hard tasks that await us—like getting out of bed. So, throughout January, we’re rolling out Getting Out of Bed, a series of stories about all things related to rest and resilience. Read more here.

This piece is part of the an issue of Black Power Naps Magazine created as a collaboration between Broadly and artists niv Acosta and Fannie Sosa, which aims to interrogate racial equity and promote rest and healing among Black people. Read more here, or pick up a print copy at Performance Space New York through January 31, 2019.