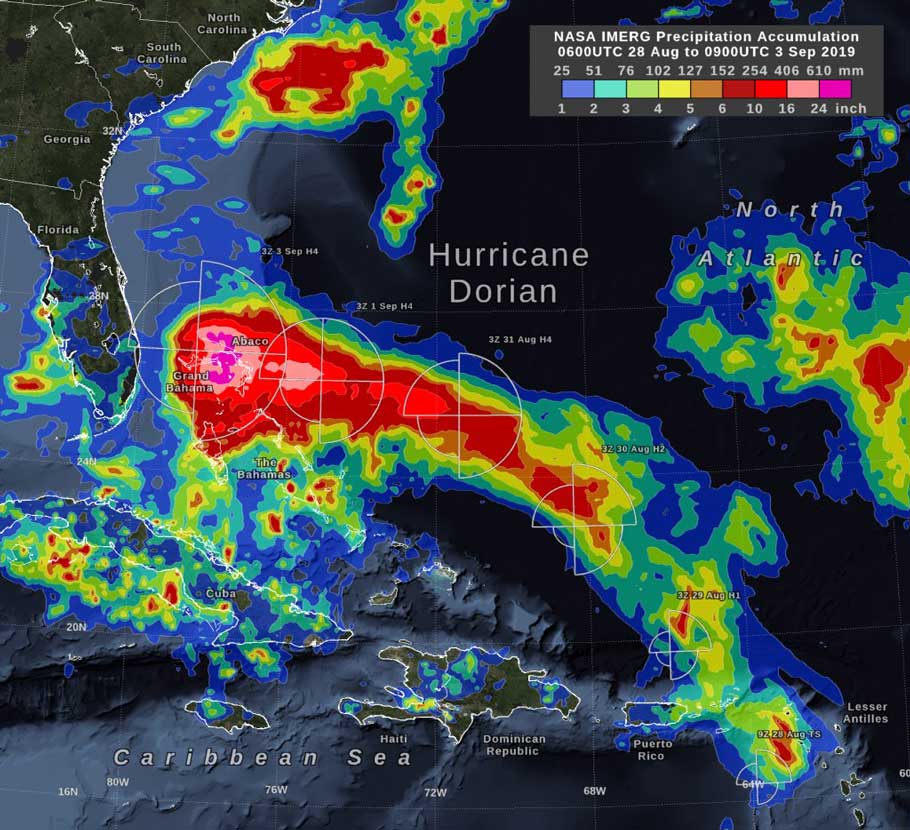

Astronaut Nick Hague posted this photograph of Hurricane Dorian to Twitter from the International Space Station. By Tuesday afternoon, the storm had spent 40 hours parked over Grand Bahama Island and dumped 24 inches of rain. NASA

The storm evolved swiftly and unpredictably. But it was other weather phenomena that caused Dorian to stall, devastating the island nation.

Jason Dunion has been flying on “hurricane hunter” planes for the past 20 years to collect data on tropical storms. Yet Sunday’s flight into Hurricane Dorian was the first time he had felt the awesome power of a Category 5 storm.

Dunion, a scientist at a National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration meteorology lab in Miami, was strapped into his seat along with the 18 other scientists and crew as winds approaching 200 miles per hour buffeted the P-3 Orion, an aircraft originally designed to hunt enemy submarines. When the plane dropped suddenly, he and the others felt a few moments of weightlessness.

“It was like a roller coaster, but you couldn’t see where the turns were,” Dunion says. “It was intense. It was like nothing I had ever felt.”

Once the plane had passed through the turbulence to the calm eye of the storm, Dunion looked out the window to see a swirling maelstrom of fast-moving clouds topped by a patch of bright blue sky above. “You appreciated the beauty, but you were completely surrounded by this hostile environment.” For Dunion and other scientists, Hurricane Dorian has defied predictions of both its strength and its path toward Florida and the southeastern US. The unpredictability has kept coastal residents on edge and made it tougher for relief agencies to anticipate where the worst effects will be felt.

“We’ve seen the track change hour by hour,” says William Porter, an operations planner for Team Rubicon, a disaster relief group comprised of US veterans. Porter says his volunteers have been moving equipment and supplies around the southeastern Atlantic coast in anticipation of Dorian’s eventual US landfall. On Tuesday morning, the first of its teams landed in Nassau, the capital of the Bahamas, to help assess the island’s damage. “If you look at what the storm was predicted to be a week ago versus what it is today, I don’t think anyone could have seen this significant a change.”

By all accounts, Dorian started out as a hurricane weakling. At first, Dorian was a loosely organized, slow-moving disturbance that was crippled by dry air from a Saharan dust storm that had moved over the middle of the Atlantic Ocean, according to NOAA’s Dunion. Hurricanes need warm water and air that rises rapidly into a moisture-rich atmosphere to grow. The Sahara’s dry air and dust particles, which can fill the air up to 20,000 feet, initially stifled the evolution of this storm.

After surviving the Saharan dust, however, Dorian headed northward across the eastern tip of Puerto Rico, then turned east and chugged across the Caribbean, picking up energy from the warm surface waters. That energy fed Dorian’s rapid intensification from Category 4 to Category 5 on Sunday—just as Dunion was flying through it.

By Labor Day weekend, NOAA forecasters updated their predictions: Dorian would stall before hitting Florida. That announcement was a big relief to the 6.7 million residents of South Florida, but bad news for the 70,000 people living in the Bahamas. By Tuesday afternoon, it had already spent 40 hours parked over Grand Bahama Island and dumped 24 inches of rain. Bahamas Prime Minister Hubert Minnis called Dorian’s trail of destruction a “historic tragedy.” So far, authorities say five people have died, but the death count is expected to rise.

This graphic shows storm-total rain accumulation over parts of Grand Bahama and Abaco islands, as well as the distance that tropical-storm force (39 mph) winds extend from Hurricane Dorian’s low-pressure center, as reported by the National Hurricane Center. Source: Nasa

Dunion says he was surprised at how fast Dorian grew from Category 4 to Category 5. “Usually you don’t see rapid intensification in just one day, usually that happens to weaker storms because they have more room to grow,” he says. “We went from Cat 4 to an extremely powerful Cat 5 in just a few hours. That was something that doesn’t happen very often.”

The storm stalled over the Bahamas because it was squeezed between two high-pressure systems, one to the northeast over the North Atlantic and one to the northwest over the US. Those intense wind currents prevented the storm from continuing its trek up toward the US coastline. Dorian has now dropped to a Category 2 hurricane. With those high-pressure systems now weakened, NOAA forecasters say the storm will head north along the Florida coast reaching South Carolina late Wednesday. It’s still not clear where it will make landfall, although widespread flooding and storm surge are expected all the way up to North Carolina’s Outer Banks.

Scott Braun, a research meteorologist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, says that weather systems hundreds of miles away have been altering Dorian’s track. “The NOAA forecasts have been very good given the inherent uncertainty of a complicated system like this,” Braun says. But modeling a hurricane is inherently challenging, especially the farther it is from land. Satellites currently measure atmospheric wind speeds by watching the movement of clouds. But those measurements might not account for winds above or below a cloud. Barometric pressure readings are also difficult to detect remotely yet are key to accurate forecasts. “None of the measurements are perfect,” Braun adds.

Scientists say they are unable to link global climate change to the path or strength of a single hurricane, but they agree that warming sea surface temperatures contribute to a storm’s rapid intensification. Yet some of that effect may be tempered by the dry air spreading west across the equator from the Sahara Desert, an atmospheric condition which has also been linked to climate change.

“You are routinely seeing temperatures in the tropics 1.5 or two degrees warmer than normal,” Braun says about this hurricane season. “That tells you there’s more energy out there. The potential is out there for more storms, but it’s just a question of whether the atmosphere provides that favorable window.”

Braun and Dunion agree that scientists need a lot more meteorological data from places where they aren’t getting it right now, like the middle of the Atlantic Ocean, where hurricanes are created. Until then, Dunion and colleagues will keep running missions in the modified P-3 Orion aircraft. Dunion flew another leg through Dorian Tuesday morning and could see and feel that the winds had begun to weaken; there was no airborne rollercoaster this time.