Keynote speech by Prof. Verene Shepherd during symposium on reparations in Trinidad and Tobago on November 13, 2019.

By Prof. Verene A. Shepherd

Director, Centre for Reparation Research, The UWI

Thank you Dr. Pemberton and good afternoon to everyone in this distinguished audience. Of course I must pay my respects to Prime Ms Erica Williams-Connell; Dean Cateau and her team of organizers; fellow presenters, reparation advocates, students, members of the media.

I have big shoes to fill this evening and it is a daunting task. The Vice Chancellor of the UWI, Prof. Sir Hilary Beckles, who is also Chair of the CARICOM Reparation Commission, was slated to deliver the keynote; but competing schedules made it impossible for him be here. So here I am shaking in my smaller shoes but still ready to step into the conversation that we have been having all day.

Now, those of you who have read Capitalism and Slavery from cover to cover – and I have a feeling that applies to everyone in this audience – might be saying to yourselves, Eric Williams never expressed explicitly a view about reparation or reparatory justice in his path-breaking work, so how does it become a Handbook for the Reparation Movement? You may even say that the strongest “R” word he used was “Resistance”, as he laid out in Chapter 12 – “The Saints and Slavery” – the role of the enslaved in the anti-slavery struggle, as the sinews of empire fought back. But while Eric Williams may not have written Capitalism and Slavery to directly support the reparation cause as it is formulated and articulated today, it has now become an indispensable handbook for all those seeking the evidentiary basis for the reparation claim against Britain.

There are those who say that Williams had another focus – not restitution for colonial wrongs. Adom Getachew, in her February 2017 article “Reparation and the Recasting of Eric Williams Capitalism and Slavery”, suggests that Williams was pursuing a different path in the modern period of decolonization. Getachew states that: “writing at the dawn of decolonization, when the promise of the postcolonial state’s capacity to transform the legacies of colonialism was as yet untested, Williams placed his hopes in anticolonial nationalism and postcolonial institutions, not reparation as it is now articulated, as engines of transformation. His vision was couched in the language of independence and autonomy, and his political imagination was structured by a commitment to, and faith in, the capacity of the state.”

So for her, “the answer to the problem of dependence for Williams was not a demand for reparation[s] but the creation of a West Indian Federation.” Getachew does remind us that in his concluding remarks at the 1943 conference co-organized at Howard University with Rayford Logan and Franklin Frazier, Williams reiterated what he wrote in Capitalism and Slavery; that Caribbean economic predicament was attributable to the development of Europe at the expense of the Caribbean; but, she says, he argued that Federation would make possible an economic development, that was otherwise impossible, and give the Caribbean area a bargaining power in the world which its isolated units did not then have.

A unified political and economic structure, Williams and other Caribbean federalists hoped, would redirect Caribbean economies towards producing the goods needed domestically and create a programme for development and industrialization. Federalists believed that, over time, the federation would transform dependence into self-sufficiency. Added to this, as Prof Stephen Vaccianni wrote in his 2016 piece in the Jamaica Observer, it was occasionally posited that closer union would strengthen labour unity in the region and create stronger bargaining power for the Caribbean entities as a whole in international negotiations. He recalled a 1956 address at Woodford Square in which Eric Williams put the matter of small size in its context: “The units of government are getting larger and larger…federation is inescapable if the British Caribbean territories are to cease to parade themselves to the twentieth-century world as eighteenth-century anachronisms.” As Sir Shridath Ramphal also noted, “In an interdependent world which in the name of liberalization made no distinctions between rich and poor, big and small, regional unity was compulsive. As we now know, the Federal project collapsed in 1962, ending Williams’s vision of a preferred model for a self-sufficient and independent Caribbean.

It was not a happy outcome for Britain, which had its own expectation of federation. Despite its debt to the region, Britain was anxious, as Gordon K Lewis claims in The Growth of the Modern WI, to use federation as a means of discarding its then unwanted responsibilities as a colonial power. But this was something that Williams had always recognised, as his daughter Erica reminded us this morning. He was always clear about Britain’s responsibility to the Region and refused any economic injection he reagarded as unacceptable. Afterall, it was he who said”The British Empire was a magnificent superstructure of America commerce and naval power on an African foundation” – a clear recognition of what Britain owed to African people.

However, by the 1960s, others had started to posit the view that formal independence and nationalism had failed to fulfill the promises of development, democracy, and autonomy and that reparation was a better option. In other words, unlike Williams, others used the “R[eparation]” word. The reparation demand rests on the political claim that slavery and the trade in enslaved Africans were crimes against humanity; that these crimes are deeply connected to contemporary global inequalities and that the root of these crimes are traceable to the fact that slavery and the Maafa enriched Europe and impoverished the Caribbean.

Gordon Lewis hinted at this when he wrote in the Growth of the Modern West Indies that: “Britain sought withdrawal from the Caribbean area without providing the sort of economic aid to which, on any showing, the colonies were entitled.” Sir Ellis Clarke, who was the Trinidadian Government’s United Nations representative to a sub-committee of the Committee on Colonialism in 1964, had been more forthright and unambiguous in his justification for reparation. He had realized that nationalism and independence would not by themselves fulfill the aspirations of Caribbean people for progress and development. His view was that

“An administering power… is not entitled to extract for centuries all that can be got out of a colony and when that has been done to relieve itself of its obligations by the conferment of a formal but meaningless – meaningless because it cannot possibly be supported – political independence. Justice requires that reparation be made to the country that has suffered the ravages of colonialism before that country is expected to face up to the problems and difficulties that will inevitably beset it upon independence.”

Anything less than that…. Sir Ellis Clarke concluded, “would constitute something less than the genuine article; it would be trying to fob off West Indians with independence on the cheap, a view later shared by Gordon K. Lewis. Ellis went on to suggest that Britain was not facing up to its moral and financial obligations.

Bruce Seely agrees that the new nations should have pressed for compensation at independence, maintaining that “the new nations, founded with much hope, faced daunting economic challenges. Quoting A. Ahmad and A.S.Wilkie in their joint 1979 article “Technology transfer in the new international economic order: options, obstacles and dilemmas”, he repeated their idea that: “These nations soon began to realize that political freedom could not be construed as an end in itself and that achieving it did not automatically ensure the social and economic well-being of their people.”

But it took several decades after Clarke, Lewis and Seely, for Heads of Government of CARICOM, the union of States that Williams helped to build despite his disappointment over Federation, to realise that, as Getachew put it, “we live in an age that can no longer conceive of its aspirations for postcolonial futures in the terms and idioms that animated Williams and other federalists.” Of course, individual politicians had been in the movement before 2013; but it was in 2013 that CARICOM as a collective, formally placed its hat in the reparation ring and publicly spoke in collective terms about reparation.

CARICOM, might not be the grand unifying, pan-Caribean project of Federation as conceived by Willams, but it has stepped in to share in the activism of Rastafari, Civil Society and Academics and taken up the mantle of finding a solution to the underdevelopment which is a legacy of British colonialism. A discarded and marginalised Caribbean in the British economic and political project has now returned to make the case for reparation, using Williams’ 1944 argument in Capitalism and Slavery as well as his vision of British responsibility, that Britain’s rise to a position of global power had been dependent on the Caribbean and Africa; but as decolonization had not been met with adequate financial support, the time had come to confront Britain and other complicit Nations about their obligation.

It was at their Thirty-fourth Regular Meeting of the Conference of Heads of Government of CARICOM held in Trinidad and Tobago in 2013, that Heads took a decision to align themselves formally with the reparation movement and to press European Governments for reparation. They agreed to set up National Committees on Reparation in each CARICOM State where none existed (only Jamaica had one at the time); and to establish the moral, ethical and legal case for the payment of reparation by the former colonial European countries, to the nations and people of the Caribbean Community, for native genocide, the transatlantic trafficking in Africans, a racialized system of chattel enslavement and an unjust colonial and neo-colonial system which continued to harm the region.

By 2014, National Committees had been established in Antigua and Barbuda, Barbados, Belize, Guyana, Jamaica, St. Lucia, St. Vincent and the Grenadines, Suriname, Dominica, Trinidad & Tobago and the Bahamas, with members drawn from a wide cross section of Caribbean society – Rastafari, academics, legal practitioners, grassroots organizations, church leaders, artistes; and they established links with reparation activists and networks in the non-independent Caribbean countries of Guadeloupe, Martinique, the British and US Virgin Islands and the Dutch-colonized Caribbean. Links were also established with reparation committees and organizations in Africa, Asia, Canada, the EU, Latin America, the UK and the USA; for what CARICOM has joined is a global African reparation movement. Unfortunately, only 3 currently exist offiically – in Antigua/Barbuda, Jamaica and Guyana – as some CARICOM Heads have reneged on their responsibility.

Heads mandated the establishment of a CARICOM Reparations Commission (CRC), led by a Core Committee (i.e., a Chair and 3-Vice-Chairs), and comprising the Chairs of the National Committees; and a representative of the University of the West Indies (The UWI). The Core Committee and the Chairs of Nationa,l Committees report directly to a Prime Ministerial Sub-committee on Reparations, comprising the Heads of Government of Barbados, St. Vincent and the Grenadines, Haiti, Guyana and Suriname, who would provide political oversight. Heads of Government also requested that The UWI establish a Centre for Reparation Research to support the CRC.

By joining the movement, CARICOM was signalling that decades after Independence the people of the Caribbean are still struggling to achieve true economic independence and sustainable development, end poverty and make the region less vulnerable to the ravages of natural and man-made disasters and the impact of climate change and centuries old environmental degradation. While a multiplicity of strategies has been pursued by the post-colonial political regimes in their efforts to overcome socio-economic, environmental and political challenges, as Western European Powers left the region un- and under-developed after having used our resources, with indigenous and forcefully imported labour, to ensure their own development, reparation as part of decolonial justice for such under-development has been placed on the table. The argument is that the work of remaking the Caribbean is not possible without restitution.

The next task mandated by the Heads of Government was the drafting of a generic letter to be sent to 6 Europeans countries that had colonized the region and enslaved its African ancestors: the UK, Portugal, Spain, France, The Netheralnds and Denmark, setting out the main reasons for the reparation demand. Capitalism and Slavery had long showed that the trade and slavery engulfed a diversity of nations, with the first to start passing the baton to another.

To help to build the case for reparation, Capitalism and Slavery became an indispensable handbook. The claim had to show Britain’s role in almost wiping out the indigenous people, specifically in the Eastern Caribbean; in conceptualizing and financing the enterprise that become chattel slavery; its culpability in the trafficking of Africans; its links to slave trading companies like the Royal African Company; the rise of its cities and ports because of slave trading; the enrichment of its citizens from all walks of life because of the exploitation of unpaid African labourers and the profits generated from colonial outputs; its use of slave generated wealth to establish industries and financial institutions; its militarization of the Caribbean to suppress African protests and ward off competitors; its cruelty and barbarism towards Africans; its resistance to emancipation and when it capitulated, its payment of compensation to the enslavers, while leaving the formerly enslaved with nothing but freedom in Eric Foner’s formulation and its continuation of the mentalities and ideologies of slavery into the post-slavery period. The impact of these are proving hard to dislodge. African people are still walking in a circle, so vividly represented in 2015 Manbooker prize winner Marlon James’ historical novel, The Book of Night Women: “Every Negro walks in a circle. Take that and make of it what you will. A circle like a sun, a circle like a moon, a circle like bad tidings that seem gone but always comes back.s

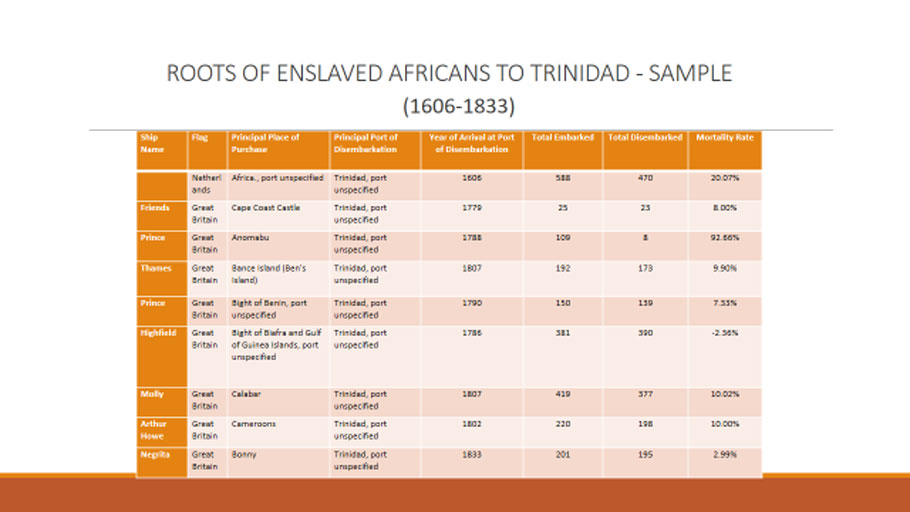

Roots of enslaved Africans to Trinidad (1606-1833).

Capitalism and Slavery has served reparation activists well. It is afterall, a study of the contribution of slavery to the development of British capitalism. Williams makes it clear that the Caribbean was central to capital accumulation in Europe and that slavery was critical to the making of British (European) modernity. The transatlantic trade in Africans and plantation slavery and associated enterprises made industrialization in England possible as they did the emergence and profitability of financial institutions. Capital generated from the Caribbean facilitated the development of banks; slavery profits swelled the coffers of towns and cities like London, Bristol, Birmingham, Liverpool, Manchester; Glasgow, Edinburgh, enriched families and individuals and established schools, Universities and Churches.

.Whether or not racism was born of slavery or the other way around, the book is clear that racism came to undergird the slave system in the Caribbean. The means by which black bodies were mobilised to create profits added to the crime against humanity. We know that Spain, Netherlands, USA and Britain traded Africans to this twin Island Republic. Between 1606 and 1833, 101 voyages were undertaken by these traders to Trinidad with 25, 285 of the 28,249 who embarked on slavers disembarking, with an overall mortality rate of 11%. Abolition of the trade in 1807, effective 1808, should have saved African from this horror, but we know, based on the Eltis database 2.0 that shows ships captured and taken to Sierra Leone and elsewhere, that up to the late 19th century attempts were made to sell Africans to the region.

The labour of Africans created profits for Britain, which fuelled the industrial revolution and developed the UK’s economy & society. Postlethwayt described the TTA as “the first principle and foundation of all the rest, the mainspring of the machine which sets every wheel in motion.“ Royal families throughout Europe developed financial interests in the trade; and slavery was profitable for the British economy. One should recall that the English gave Royal patronage to the TTA and slavery through the establishment of the Company of Royal Adventurers Trading to Africa, which, after five years of operation, was recapitalized and incorporated into the Royal African Company (RAC) in 1663. The RAC was chaired by the Duke of York, nephew to the then King, and members of the royal family were prominent investors in it. This is a reason for involving the present monarchy in the reparation claim as the royal family inherited wealth from that period.

In March 2007, British M.P. Diane Abbott reminded her parliamentary colleagues that 15 Lord Mayors, 25 sheriffs and 38 aldermen were shareholders in the RAC. It is estimated that, in 1776, 40 members of the British parliament were making their money from investments in the Caribbean.

It was only economic forces combined with convenient humanitarian and political actions in the metropole and boots of black soldiers on the ground in the Caribbean that forced its demise. Up to 1783, Williams argued, all classes in English society presented a unified front with regard to the enterprise, despite knowledge of the evils manifested. But money was there to be made for opposition to triumph before 1783. Indeed, Williams was clear that “the enslaved furthered the cause of Emancipation”; that they were the objects and basis of the movement for Emancipation. Williams thesis held that capitalism as an economic modality quickly replaced slavery once European elites accumulated the vast surplus capital from slavery that they needed in order to bankroll their industrial revolution. As a result of the evidence that Williams amassed against Britain, J.A Rogers, in his review of Capitalism and Slavery, according to Colin Palmer, “complimented Williams for showing better than I can recall ever having seen what the New world owes to the Negro, the victims of slavery and the slave trade, for its development, particularly in its pioneer stage; as well as England for its rise from a small power to the world’s greatest empire;” which is why justice on behalf our African ancestors features so prominently in reparation activism.

Caricom’s Reparation Strategy

So using the evidence from Capitalism and Slavery as the foundational text and adding other books on similar themes published since, along with Archival Records to which Williams may have access or perhaps never thought of using, the governments of CARICOM, through the CRC, have articulated the justification for the reparation demand. The CRC stresses that the region’s indigenous and African descendant communities who are the victims of Crimes against Humanity in the forms of genocide, enslavement, human trafficking, deceptive Asian indentureship and racial apartheid have a legal right to reparatory justice, and that those who committed these crimes, and who have been enriched by the proceeds of these crimes, have a reparatory case to answer. The plan recognizes the special role and status of European governments in this regard, being the legal bodies that instituted the framework for developing and sustaining these crimes and served as the primary agencies through which slavery based enrichment took place, and as national custodians of criminally accumulated wealth. Its justification can be summarized as follows:

- The injustice is well documented

- Plantation slavery provided the scaffold for Britain’s industrial advancement

- A defendant (or perpetrator) exists

- The victims are identifiable as a distinct group

- The descendants of victimised groups continue to suffer harm. This remains true today as the institutionalised racism of the colonial era has had a debilitating impact on Africans and people of African descent.

- Colonialism has economically disfranchised Africans and people of African descent.

- There is precedent for the payment of reparation (Ayiti; Jews; British planters)

- It is supported by Clause 158 of the Durban Declaration & Programme of Action (DDPA), which recognizes that… “historical injustices have undeniably contributed to the poverty, underdevelopment, marginalization, social exclusion, economic disparities, instability and insecurity that affect many people in different parts of the world, in particular in developing countries; and recognizes the need to develop programmes for the social and economic development of these societies and the Diaspora, within the framework of a new partnership based on the spirit of solidarity and mutual respect.”

- The right to reparation is recognised by International Law, which allows for the claiming of reparation by the descendants of victims.

- Compensation was paid to the enslavers and their beneficiaries, but not to the enslaved.

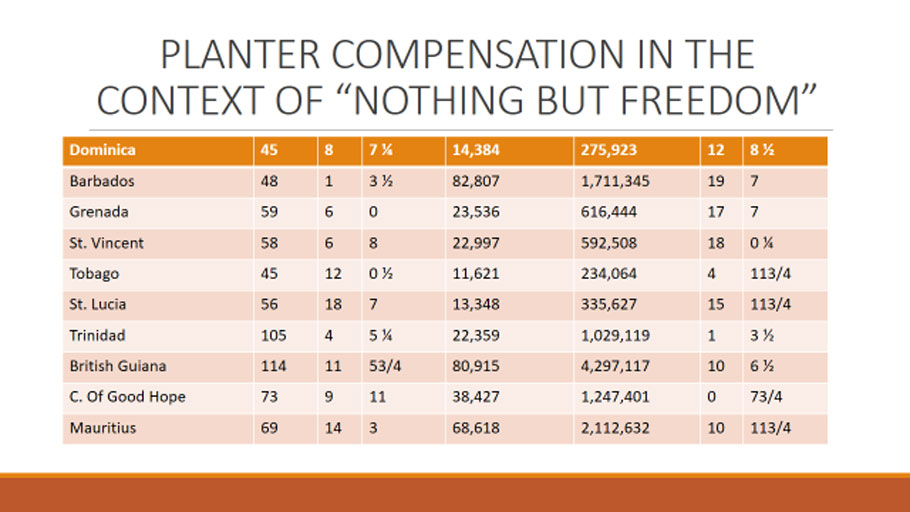

Planter compensation in the context of “Nothing but freedom”.

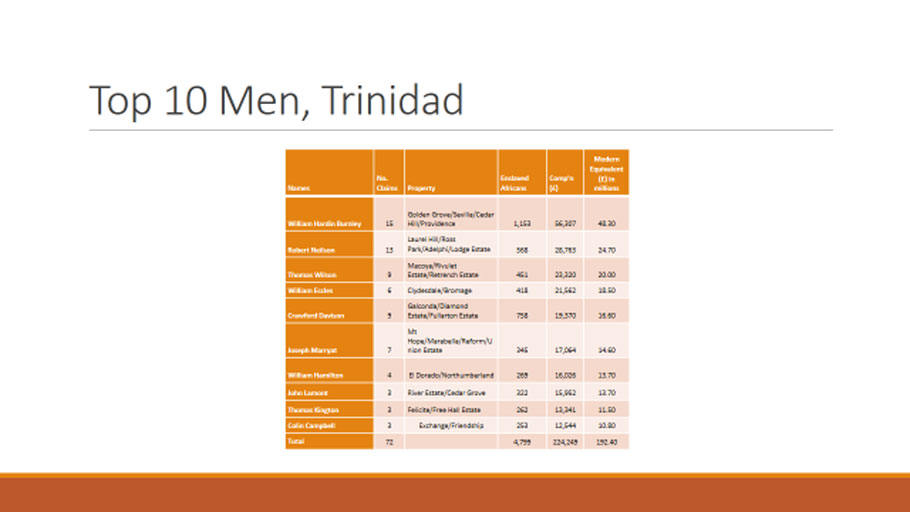

For example, planters of Tobago received 234,064 thousand pounds of the £20M [£201M in 2018 calculation]; and those in Trinidad £1,029,119 or £883M today. Williams did not do a full analysis of the Compensation Claims as University College London (UCL) has now done, although he did name some individual beneficiaries; but thanks to the UCL team, I can share the top 10 male and female beneficiaries in Trinidad. The highest payout of £48.3M in today’s money went to William Hardin Burnley, who topped the top 10 male beneficiaries list for Trinidad (and the total for the 10 was £192.4M); while the top 10 enslaver women for Trinidad received

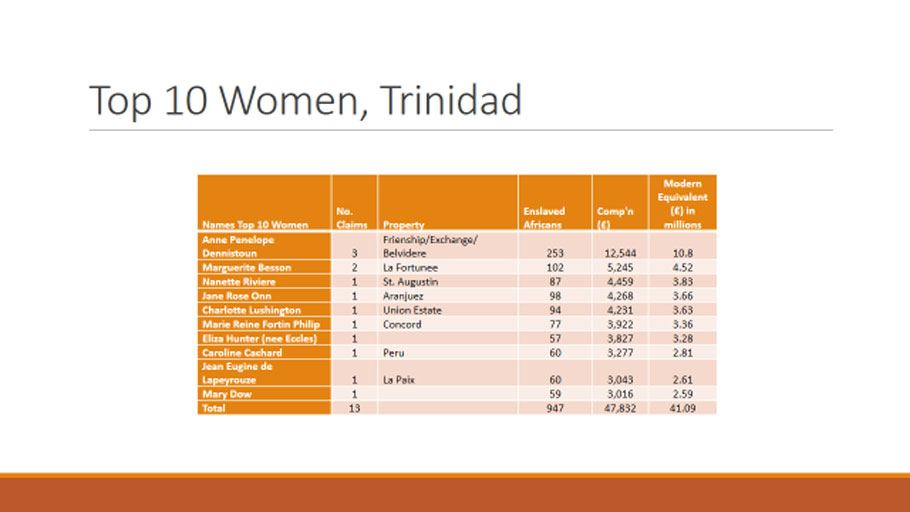

£41.09 M, with Anne Penelope getting the highest pay-out of £10.8M in 2018 equivalent.

Top 10 Women, Trinidad.

Top 10 Men, Trinidad.

The negotiating strategy to seek justice, for now, is theTen Point Action Plan. Before setting out the plan, I admit that The DDPA and the POA for the Decade have suggested solutions for how States can address the crisis of underdevelopment in post-colonial societies. But those solutions are rather vague and non-binding and are framed within the context of what David Martin terms “lexical colonialism,” with insufficient emphasis placed on the recipient and not enough empowerment of the “recipient” to deal with the “artefact being transferred”.

The 10 Point Action Plan starts with a claim for a [1] Full Formal apology (which is different from a statement of regret or deep sorrow): it has 3 dimensions: responsibility, repair, non-repetition. It follows with the other 9:

[2] An Indigenous Peoples Development Programme

[3] Repatriation for those who desire it.

[4] The establishment of Cultural Institutions in the region

[5] Addressing the Public Health Crisis in the region

[6] Illiteracy Eradication /expanded education infrastructure

[7] The development of an African Knowledge Programme to rebuild the bridge of disconnection

[8] Infrastructure for Psychological Rehabilitation

[9] Technology Transfer, which can be located within the right to development framework of the United Nations.

The right to development focus is not only captured in the work of the UN, and the works of Eric Williams and other scholars like Beckford and Lewis, who established for us the roots of Caribbean under-development, but also in the artistic expressions of our singers. In this verse from Slave Driver, the Honourable Robert Nesta “Bob” Marley wailed,

“Every time I hear the crack of the whip

My blood runs cold

I remember on the slave ship,

How they brutalize the very souls

Today they say that we are free

Only to be chained in poverty….

Slave driver the table is turn.”

Marley’s song not only reflects the memories of ancestral suffering via the transatlantic trade in enslaved Africans; but the lines “today they say we are free; only to be chained in poverty” could very well have been commissioned by the CARICOM Reparation Commission. The Programme of Activities of the Decade for People of African Descent, grounded in the Durban Declaration and Programme of Action, emphasizes the need for apology, repair and reconciliation as a way of closing the dark chapters in our history.

[10] Finally, the Caribbean reparatory Justice Programme includes Debt Cancellation and monetary compensation- on the basis that the Caribbean governments that emerged from slavery and colonialism have inherited the massive crisis of community poverty and institutional unpreparedness for development. The pressure of development has for too long driven governments to carry the burden of public employment and social policies designed to confront colonial legacies.The post-independence demand for development with input from former colonial powers, still continues, especially as nationalist leaders, anxious to capitalize on the “prostrate condition of European nations after World War II,” in Bruce Seely’s words, never pressed for compensation.

Support and Opposition:

Let me hasten to say though that the rightness of the reparation struggle is not self-evident to all and even if the right to reparation is recognised by International Law. Opposition abounds, using the following arguments:

- Too long ago in the past

- There are no victims/they are all dead

- Descendants cannot claim on behalf of their ancestors

- The majority of Caribbean people are not in favour of the movement

- Caribbean people are opposed to repatriation

- It was Africans who sold our ancestors

- Too complicated a matter

- Governments cannot pay

- “… the horrors of slavery cannot be used to justify reparation for individuals of African descent residing in the Caribbean

Massa Day Nuh Done:

But every idea or movement faces its opposition, no matter how unfounded the arguments. Williams faced his own critics as we know, with a few dismissing his arguments with venomous assaults, according to Selwyn Carrington, rather than with reasoned arguments, careful research and analysis”.

The begging bowl, mendicancy argument is rife among Caribbean people, reminding me of D. A. Farnie’s criticism of Williams’ Capitalism and Slavery, which he said “presented the author’s own community with the sustaining myth that capitalism was responsible for their condition, a view that has not found favour with Western Europe…”

Western Europe’s views in the contemporary period are well known, based on the public statements we have seen especially since 2004 when President Aristide of Haiti made a call on France and since 2007 when during the Bicententenary of the passing of the British Act to end the trafficking in enslaved Africans, reparation from Britain was placed in the spotlight. While their universities – Bristol, London, Cambridge, Glasgow, Edinburgh, Oxford, etc – are busy studying their role in slavery, with Glasgow actually stepping forward with a £20M reparation package, States have remained unmoved. The movement in the USA has also intensified and you may have seen that Georgetown, Princeton, Harvard and others are making gestures of apology and repair. The PM of Antigua in ensuring that Harvard does get to decide by itself what should be the level of repair and has called them out to invest in his country based on firm evidence that the enslaver , Isaac Royale, who started Harvard Law school, made in money in Antigua. But the stance of the UK has mirrored that expressed by former PM Tony Blair in 2007, statements made by former UK PM, David Cameron, Lord Tariq Ahmad, British Minister of State with responsibility for the Caribbean, Commonwealth and the United Nations and the current UK High Commissioner in Jamaica, Asif Ahmad – all aimed at detaching the modern legacies of chattel enslavement and redirecting it to modern human trafficking and other current human rights issues. In an interview with journalist George Davis in May this year, British High Commissioner to Jamaica, Asif Ahmad says the long discussed matter of reparation for slavery is not a priority item for Britain at this time. He says while the issue has been raised over the years by advocates, it has not been placed on the government’s political agenda.

The leader of the Opposition Labour party in the UK disagrees, I see; so do some people in Jamaica, judging by two cartoons which appeared in the wake of anti-reparation statements by British politicians and the pushback from former PM, P.J. Patterson who insited that:

Confined to the Past?

In the news: Cartoonist weighs in.

But, because Massa day nuh done, and the procolonialists are seeking to destabilise the reparation movement, the road has become harder. In Eric Willaims’ formulation, Massa stood for colonialism; and even with the postcolonial social revolution that should have made massa irrelevant, the massa mentality of pro-colonialism is hanging around. As evidence, scan the regional newspapers to see how some of the descendants of enslaved Africans are reacting to the reparation discussion, bigging up massa even though Williams told us that “that massa developed the necessary philosophical rationalisation of our relationship with him, which is that the workers, both African and Indian, were inferior beings, unfit for self-government, unequal to their superior masters, permanently destined to a status of perpetual subordination, unable ever to achieve equality – whether in occupations, skin colour, legal systems and economic systems.” [p. 243]

Howard Rennie opines,

- “Caribbean nationals are not entitled to, and will never get reparation for slavery because from ancient times until it was abolished in the 19th century, slavery was regarded as a natural institution and was practised by all ancient civilizations. There was no universal law against it and it was regarded as a natural part of life for humans to enslave humans deemed weaker by virtue of economic standing and military might. Planters in the Caribbean were not slave raiders; they obtained slaves by purchasing them from sellers. Since the planters used their money to purchase “tools with voices”, then legally, these “tools” were added to the planters’ assets, which would be used to bring them greater wealth.”

- The late Michael A. Dingwall addressed his letter to the British PM in 2015

“Mr. Prime Minister, there is currently a well-organised effort in the Caribbean to get your country to pay us black descendants of African slaves in this region reparations for slavery. While some of our intellectuals think that the reasons are sound, I, a proud black man, think that the reasons are not only baseless but also insulting. While we black people in the West have been fed a steady diet of anti-white propaganda that we blacks were victims of the evils of your ancestors, the truth tells a very different story. In several ways, it can be argued that your government has already paid reparations. Firstly, our ancestors in Africa were paid. Secondly, during the 1960s and later, your country gave us these priceless islands. Thirdly, your government has helped to sustain us with generous technical and financial grants and assistance. Why give us another economic bailout with reparations? Please, don’t insult our pride with more handouts such as reparations.”

I am sure similar ones have appeared in your newspapers here; although, to be honest, when I compare the public education tradition led by academics and politicians in the region, I think that the people of Trinidad and Tobago had the best preparation, maybe only topped by Haiti and Cuba, with Jamaica following behind you. Your Prime Minister wrote and taught you to be nationalistic but also anti-colonial; and he laid the foundations for you to understand why the enslaving power required even more conquests. In 1960 he told you that there were only two alternatives available to you – forward to independence or backward to colonialism. You not not only became independent, you went on to become a Republic because you wanted to be sure that Massa Day Done! But since even Williams later admitted that political independence set the stage for, but does not guarantee economic independence, you have to take the baton a little further than he did and use reparation as an indispensable part of the search for economic independence. To get there we need Caribbean unity – a still unrealised ideal.

So why does the movement for reparatory justice still occupy the energies of so many people, especially within the culture of disunity and the presence of vocal anti-reparationisists? Can we really destabilize white supremacy, which many see as the obstacle to reparatory justice? Is Historian Nell Painter right when she asserts that the racial “idea of blackness” would likely always be with us, meaning also that white supremacy will always be with us? How do we treat with the idea, that as Ta -Nehisi Coates observes, while the black political tradition is essentially hopeful, history shows us too many examples of heroic people whose struggles were not successful in their own time, or at all? On the contrary, to the extent that they were successful, black politics was a necessary precondition, but never enough to foment change?

Coates admits that not even emancipation should be viewed as a triumph of black activism or the moral force of the actions of the just over the unjust. He holds that “It became impossible, for instance, to think about emancipation without the threat presented by disunion, to talk about the civil-rights movement without the ghost of Nazism or the Cold War. It began to seem to me that black politics was the wind at the American window. At rare moments the window opened and black people pushed through. The window seemed to open for one reason and one reason alone—some threat to white interests becoming intolerable.” In this formulation, it is not enough to be hopeful that good will triumph over evil because “ “Hope” [might be] an overrated force in human history – unlike fear”

So what will be the wind at the Caribbean window that will open up, create fear among former colonizers to enable the cause of reparatory justice to push through, especially in the face of the tenacity of white supremacy and the tenacity of injustice?

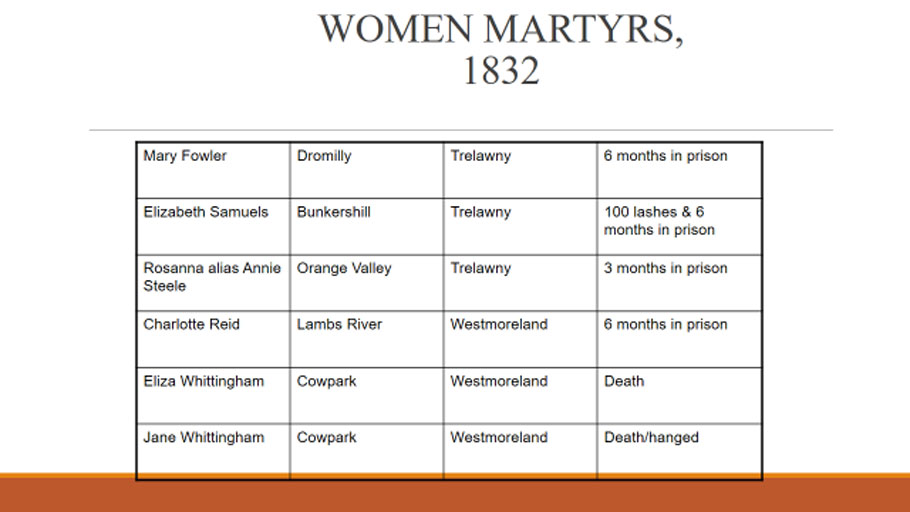

I do not have all the answer. All I know is that, ahistorical as it may seem to some, we in the reparation movement have decided not to live in hopelessness, but to push on – if only in memory of our ancestors. [see sample from punishment list in Jamaica]

Women Martyrs 1832.

With the recent reparatory justice moves among institutions, it is clear, as Nelson Mandela once said when apartheid was toppled, ” it always looks impossible until it happened”. We who believe in freedom cannot rest until it comes; which is why, using the direction left by Capitalism and Slavery, the CRC is drafting more detailed letters to 12 European States setting out their exact involvement in, and benefits from, African enslavement.

Thank you Eric Williams for leaving us your inspirational writings that contain the proof that may take us to Zion. Continue to rest in power!

Related Article 1

Regional Reparations Symposium honours work of CARICOM Founding Father, Eric Williams

Presiding Officer Tobago House of Assembly Legislature, Denise Tsoiafatt-Angus , Dir. of the Centre for Reparations Research, Prof. Verene Shepherd, and daughter of Eric Williams, Erica Williams.

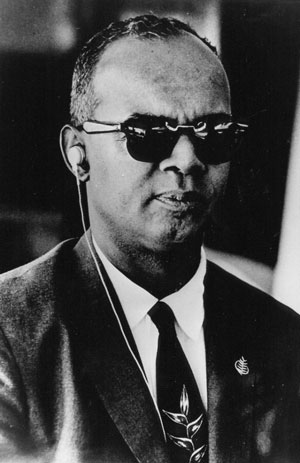

The work of one of the four founding fathers of CARICOM, Dr. Eric Williams, is currently being honoured during a symposium at the University of the West Indies (The UWI) in Trinidad and Tobago.

The two-day Symposium tilted “Capitalism and Slavery – 75 Years Later” is happening at the Faculty of Education Auditorium, the UWI, St. Augustine Campus. The CARICOM Reparations Commission is collaborating with the UWI Centre for Reparation and the Faculty of Humanities and Education UWI, St. Augustine to host the Symposium. Its purpose is to commemorate the 75th year of the publication of Eric Williams’ Capitalism and Slavery on the 13th of November.

CARICOM Founding Father from Trinidad & Tobago Dr. Eric Williams.

The symposium examines Williams’ Caribbean Vision, the profits from enslavement in the 16th to 19th century, the impact on Capitalism on the World today, Capitalism and Slavery and Reparations, Capitalism and Global Connections as well as Decolonising Caribbean History. The organisers sought to gather scholars, intellectuals, corporate interest groups, artists and activists to examine the impact of Williams and his work on the Contemporary Caribbean and the wider world.

Speaking at the opening of the Symposium on Wednesday morning, Programme Manager, Culture and Community Development at the CARICOM Secretariat, Dr. Hilary Brown, said the Caribbean Community would always remember and celebrate Eric Williams as one of the founding fathers of the regional integration movement and the community of nations now known as CARICOM. She said that as one of four signatories to the Treaty of Chaguaramas, in Trinidad and Tobago on 4 July 1973, establishing CARICOM, Eric Williams helped to lay the foundation for a far-reaching partnership, a relevant development agenda and critical path to sustainable development for the Caribbean region.

“For this we owe him a debt of gratitude,” she said.

Programme Manager, Culture and Community Development at the CARICOM Secretariat, Dr. Hilary Brown, speaking at the opening of the symposium.

Dr. Brown, who was also speaking on behalf of the CARICOM Reparations Commission, said that the Commission recognised and felt strongly that a commemorative event should be held during 2019 to highlight this historic moment and major milestone for the Region, of the 75th anniversary of the publication of the seminal work “Capitalism and Slavery” by Dr. Williams. According to her, the Symposium was the Caribbean’s contribution to the global recognition of the impact and importance of his life and work, including its relevance to the movement for reparatory justice.

“He advanced our understanding of the intersecting axes of discrimination against especially people of African descent, indigenous people and people of East Indian origin, arising from a history of institutionalised exploitation, perpetuated into the present by racism, economic, social and environmental vulnerability, extreme poverty and inequality. He wrote for us, from our perspective, so that we could better understand how our economic, political and social realities were shaped by and facilitated the economic advancement of Europe,” she said.

Williams’ daughter Erica Williams attended the Symposium and made a presentation entitled “Eric Eustace Williams: Too Big to be Small” on the first panel discussion for the day. A keynote address will be given by Director for the Centre for Reparations Research, Professor Verene Shepherd at the end of the first day of the symposium. Her presentation is titled ” Capitalism and Slavery. A Handbook for Reparation Advocates in the Post-Colonial Caribbean”.

Related Article 2

High School Students in Trinidad and Tobago engaged on Reparations, Capitalism and Slavery

Trinidadian High School Students at an engagement at UWI St. Augustine on Capitalism and Slavery.

As part of a symposium on reparations, students from more than 10 high schools in Trinidad and Tobago were invited to the UWI St. Augustine Faculty of Education for a programme of activities dedicated to Dr. Eric Williams’ work.

The symposium focuses on the book Capitalism and Slavery which was written by the former Trinidad and Tobago Prime Minister and CARICOM Founding Father 75 five years ago. It was hosted by the CARICOM Reparations Commission in collaboration with the UWI Centre for Reparation and the Faculty of Humanities and Education UWI, St. Augustine.

The interaction with the students included performances and lectures from well known historians including Director of the Centre for Reparations Research, Professor Verene Shepherd.

A performance by the UWI Department of Creative and Festival Arts

A Trinidadian scholar based at the University of Oxford, Dr. Dexnell Peters, examined the Impact of Capitalism and Slavery with the students. He encouraged those who were interested in studying history, especially Caribbean History, to pursue their studies at the University of the West Indies or regionally because it was one of the best places to learn about the Region’s history and be able to review it critically and analytically.

Dean of the Faculty of Humanities and Education at UWI St. Augustine, Professor Heather Cateau, also engaged the students. She gave a review of Dr. Williams’ book Capitalism and Slavery… 75 years later. She told them about the actual book as well as the man “Dr. Eric Williams” former Prime Minister of Trinidad and Tobago and founding father of CARICOM who began his career in the teaching profession.

Professor Shepherd, in her presentation to the students, gave a brief overview of slavery and explained the progress of the current CARICOM reparations movement. She also gave a keynote address the previous evening at the symposium where she outlined parts of the history of slavery and explored some of the accomplishments of the reparations movement. She also informed participants that the CARICOM Reparations Commission was currently in the process of drafting another round of letters to the European countries involved in slavery that would include additional countries that were not included when the first round of letters was sent.

The symposium, which concluded on Thursday, examined Dr. Eric Williams’ Caribbean Vision, the profits from enslavement in the 16th to 19th century, the impact on Capitalism on the World today, Capitalism and Slavery and Reparations, Capitalism and Global Connections as well as Decolonising Caribbean History.

On the first panel discussion on the first day of the symposium, Williams’ daughter, Erica Williams, made a presentation entitled “Eric Eustace Williams: Too Big to be Small”.

The article “Regional Reparations Symposium honours work of CARICOM Founding Father, Eric Williams” was originally published by CARICOM Today.

The article “High School Students in Trinidad and Tobago engaged on Reparations, Capitalism and Slavery” was originally published by CARICOM Today.