With a focus on racial pride and self-determination, the Black Power movement argued that civil rights reforms did not go far enough to end discrimination against African Americans.

By 1966, the civil rights movement had been gaining momentum for more than a decade, as thousands of African Americans embraced a strategy of nonviolent protest against racial segregation and demanded equal rights under the law.

But for an increasing number of African Americans, particularly young black men and women, that strategy did not go far enough. Protesting segregation, they believed, failed to adequately address the poverty and powerlessness that generations of systemic discrimination and racism had imposed on so many black Americans.

Inspired by the principles of racial pride, autonomy and self-determination expressed by Malcolm X (whose assassination in 1965 had brought even more attention to his ideas), as well as liberation movements in Africa, Asia and Latin America, the Black Power movement that flourished in the late 1960s and ‘70s argued that black Americans should focus on creating economic, social and political power of their own, rather than seek integration into white-dominated society.

Crucially, Black Power advocates, particularly more militant groups like the Black Panther Party, did not discount the use of violence, but embraced Malcolm X’s challenge to pursue freedom, equality and justice “by any means necessary.”

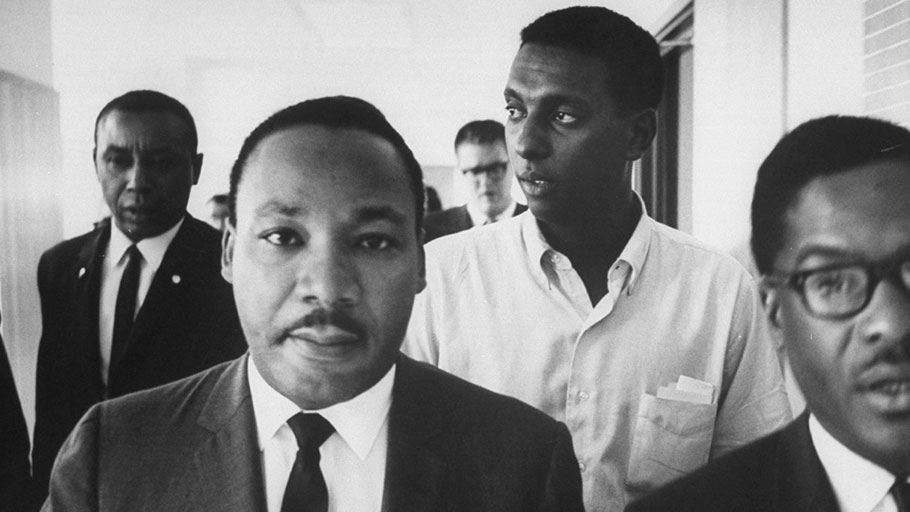

The March Against Fear – June 1966

Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. being shoved back by Mississippi patrolmen during the 220 mile ‘March Against Fear’ from Memphis, Tennessee to Jackson, Mississippi, on June 8, 1966. Underwood Archives/Getty Images.

The emergence of Black Power as a parallel force alongside the mainstream civil rights movement occurred during the March Against Fear, a voting rights march in Mississippi in June 1966. The march originally began as a solo effort by James Meredith, who had become the first African American to attend the University of Mississippi, a.k.a. Ole Miss, in 1962. He had set out in early June to walk from Memphis, Tennessee, to Jackson, Mississippi, a distance of more than 200 miles, to promote black voter registration and protest ongoing discrimination in his home state.

But after a white gunman shot and wounded Meredith on a rural road in Mississippi, three major civil rights leaders—Martin Luther King, Jr. of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), Stokely Carmichael of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and Floyd McKissick of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) decided to continue the March Against Fear in his name.

In the days to come, Carmichael, McKissick and fellow marchers were harassed by onlookers and arrested by local law enforcement while walking through Mississippi. Speaking at a rally of supporters in Greenwood, Mississippi, on June 16, Carmichael (who had been released from jail that day) began leading the crowd in a chant of “We want Black Power!” The refrain stood in sharp contrast to many civil rights protests, where demonstrators commonly chanted “We want freedom!”

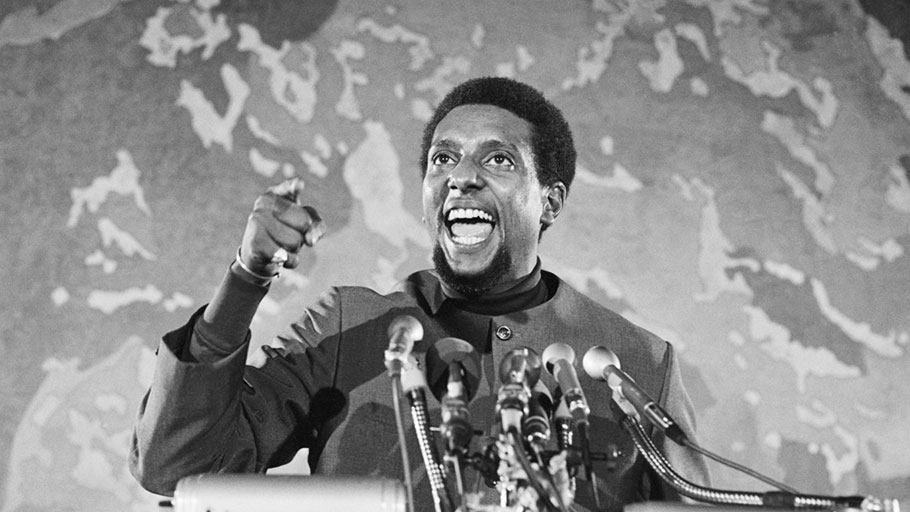

Stokely Carmichael’s Role in Black Power

From left to right, Civil rights leaders Floyd B. McKissick, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and Stokely Carmichael marching to encourage voter registration, 1966. Vernon Merritt III/The LIFE Images Collection/Getty Images.

Though the author Richard Wright had written a book titled Black Power in 1954, and the phrase had been used among other black activists before, Stokely Carmichael was the first to use it as a political slogan in such a public way. As biographer Peniel E. Joseph writes in Stokely: A Life, the events in Mississippi “catapulted Stokely into the political space last occupied by Malcolm X,” as he went on TV news shows, was profiled in Ebony and written up in the New York Times under the headline “Black Power Prophet.”

Carmichael’s growing prominence put him at odds with King, who acknowledged the frustration among many African Americans with the slow pace of change, but didn’t see violence and separatism as a viable path forward. With the country mired in the Vietnam War, a war both Carmichael and King spoke out against) and the civil rights movement King had championed losing momentum, the message of the Black Power movement caught on with an increasing number of black Americans.

Black Power Movement Growth—and Backlash

Stokely Carmichael speaking at a civil rights gathering in Washington, D.C. on April 13, 1970. Bettmann Archive/Getty Images.

King and Carmichael renewed their alliance in early 1968, as King was planning his Poor People’s Campaign, which aimed to bring thousands of protesters to Washington, D.C., to call for an end to poverty. But in April 1968, King was assassinated in Memphis while in town to support a strike by the city’s sanitation workers as part of that campaign.

In the aftermath of King’s murder, a mass outpouring of grief and anger led to riots in more than 100 U.S. cities. Later that year, one of the most visible Black Power demonstrations took place at the Summer Olympics in Mexico City, where black athletes John Carlos and Tommie Smith raised black-gloved fists in the air on the medal podium.

By 1970, Carmichael (who later changed his name to Kwame Ture) had moved to Africa, and SNCC had been supplanted at the forefront of the Black Power movement by more militant groups, such as the Black Panther Party, the US Organization, the Republic of New Africa and others, who saw themselves as the heirs to Malcolm X’s revolutionary philosophy. Black Panther chapters began operating in a number of cities nationwide, where they advocated a 10-point program of socialist revolution (backed but armed self-defense). The group’s more practical efforts focused on building up the black community through social programs (including free breakfasts for school children).

Many in mainstream white society viewed the Black Panthers and other Black Power groups negatively, dismissing them as violent, anti-white and anti-law enforcement. Like King and other civil rights activists before them, the Black Panthers became targets of the FBI’s counterintelligence program, or COINTELPRO, which weakened the group considerably by the mid-1970s through such tactics as spying, wiretapping, flimsy criminal charges and even assassination.

Legacy of Black Power

Ten-year-old Robert Dunn uses a megaphone to address hundreds of demonstrators during a protest against police brutality and the death of Freddie Gray outside the Baltimore Police Western District station on April 22, 2015. Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images.

Even after the Black Power movement’s decline in the late 1970s, its impact would continue to be felt for generations to come. With its emphasis on black racial identity, pride and self-determination, Black Power influenced everything from popular culture to education to politics, while the movement’s challenge to structural inequalities inspired other groups (such as Chicanos, Native Americans, Asian Americans and LGBTQ people) to pursue their own goals of overcoming discrimination to achieve equal rights.

The legacies of both the Black Power and civil rights movements live on in the Black Lives Matter movement. Though Black Lives Matter focuses more specifically on criminal justice reform, it channels the spirit of earlier movements in its efforts to combat systemic racism and the social, economic and political injustices that continue to affect black Americans.

This article was originally published by History.

Featured image: Photo by Bettmann Archive, Getty Images.