The response to the 2010 BP oil spill off the Louisiana coast included setting controlled burns of the surface slick. These fires added to the heavily industrialized Gulf region’s relatively high levels of particulate matter pollution, which has been found to worsen COVID-19 infections. (U.S. Navy photo of a controlled burn in the Gulf of Mexico on May 6, 2010, by Petty Officer 2nd Class Justin Stumberg via Wikipedia.)

By Sue Sturgis, Facing South —

This week marked a decade since the Deepwater Horizon offshore drilling rig exploded in the Gulf of Mexico 40 miles off the Louisiana coast, killing 11 workers and injuring 17 others and triggering the worst oil spill in U.S. history. From the initial blast on April 20, 2010, until the well was sealed four months later, 200 million gallons of crude oil poured into Gulf waters and contaminated over 1,300 miles of coastline stretching across Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, and Florida. BP was found to have been “grossly negligent” for the disaster, which led to an ecological crisis in the Gulf that continues today, with species including bottlenose dolphins and the endangered Kemp’s ridley sea turtle struggling because of it, and widespread contamination of fish.

The air and water pollution from the spilled oil and the response also created a long-term environmental health crisis for the almost 50,000 cleanup workers, many of them local residents who lost their regular jobs due to disaster-related closures of fisheries and beaches. Because the private contractors in charge of the spill response failed to provide adequate protective gear, cleanup workers were directly exposed to the oil and its fumes, to the chemical dispersants used to break up the slick, and to smoke from the fires set to burn oil off the water’s surface.

The workers tell hair-raising stories of hearing fellow employees screaming as their skin blistered, of suffering burning eyes and collapses and long hospitalizations, of neurological disorders that left them paralyzed but wracked with pain “like snakes were crawling up” their legs, of being left unable to work but buried in doctors’ bills. After their medical claims against BP led to payments that even for the most severely afflicted didn’t come close to exceeding four digits, thousands of former cleanup workers are suing the company — but they have not had their day in court yet thanks to U.S. oil spill law, which requires that financial claims be heard first.

“BP has devastated my life, it really has,” cleanup worker James “Catfish” Miller of coastal Mississippi told Huffpost. “I’m still going through it.”

These pollution-exposed workers continue to suffer medically. A recently-released long-term follow-up study carried out by researchers with University Cancer and Diagnostic Centers in Houston tracked 88 BP oil spill cleanup workers over time and found that, by seven years after the spill, most of them had developed chronic inflammation of the nasal sinuses as well as a respiratory condition similar to asthma. It also found persistent changes or worsening of their blood, liver, lung, and heart function, and it observed that the workers experienced prolonged or worsening illness symptoms.

But oil industry pollution doesn’t hurt human health in times of disaster only. It turns out that a common type of pollution emitted by the oil industry during normal operations may be making exposed people more vulnerable to the novel coronavirus now sweeping the nation — yet another blow to suffering cleanup workers, and a threat to the predominantly low-income communities and communities of color where the industry operates across the South and nation.

‘People are dying’

Along with combustion engines and coal- and gas-fired power plants, oil refineries and plants that turn natural gas into industrial chemicals are significant sources of a type of air pollution called fine particulate matter or PM 2.5, with the number referring to the particles’ size in microns. PM 2.5 pollution is made up of particles so small they can work their way deep into lungs and even penetrate the bloodstream. People living in areas with higher PM 2.5 emissions are known to suffer more heart attacks and lung problems and to die younger than their counterparts in lower-emission areas.

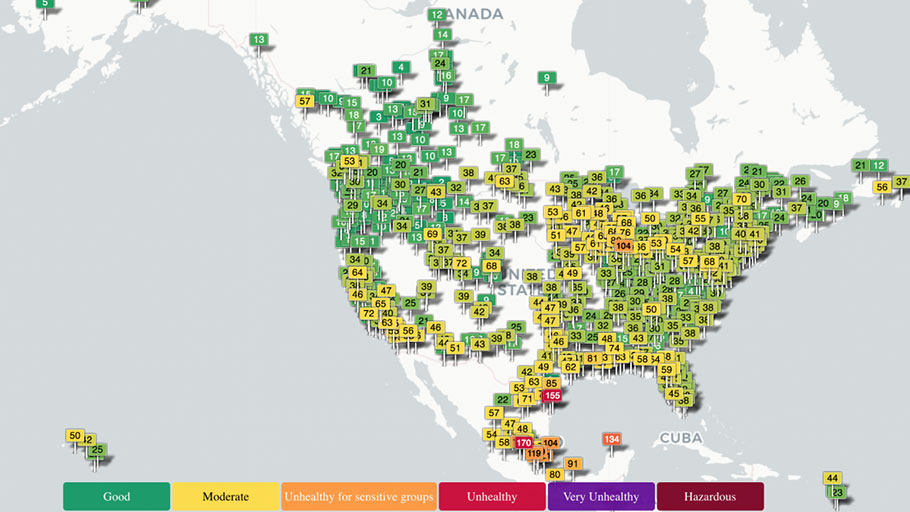

PM 2.5 pollution also increases the likelihood of dying from the COVID-19 virus — and this appears to be playing out in lower-income and African-American communities across South Louisiana, places that have long borne the brunt of pollution and other environmental damage caused by the oil and gas industry. Louisiana is among the top five states for natural gas production, and its 17 oil refineries account for nearly one-fifth of national refining capacity, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration. And as can be seen on the accompanying real-time map of air pollution captured this week, PM 2.5 levels are particularly high along the heavily-industrialized Gulf Coast.

This still of a real-time air quality map, captured on April 23, 2020, at about 4 p.m. ET, shows the relatively high levels of air pollution including PM 2.5 along the heavily-industrialized U.S. Gulf Coast.

Higher levels of PM 2.5 pollution are associated with higher death rates from COVID-19 — even after accounting for numerous factors including population size, hospital beds, number of individuals tested, weather, socioeconomics, and behavioral variables such as obesity and smoking. That’s the finding of a recent analysis by researchers at Harvard University’s T.H. Chan School of Public Health, which looked at 3,080 U.S. counties covering 98 percent of the population. It found that even small increases in PM 2.5 pollution lead to big jumps in the COVID-19 death rate. A microgram is just one millionth of a gram, 28 of which are in a single ounce, yet the study found that an increase in PM 2.5 pollution of just 1 microgram per cubic meter of air was associated with a 15 percent increase in the COVID-19 death rate. And as the pollution increases, so does the mortality risk. It’s an environmental justice issue, because African Americans are more likely to live in counties with chronic air pollution problems.

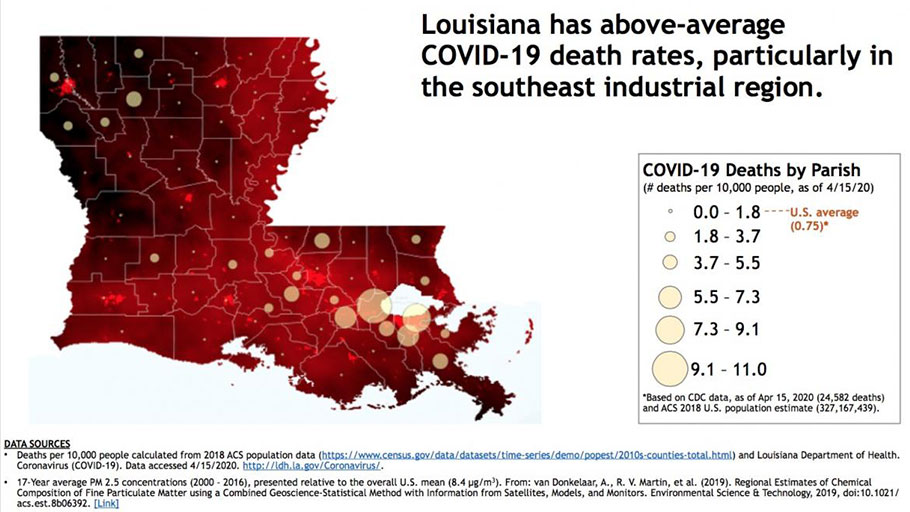

Kimberly Terrell, director of community outreach for the Tulane Environmental Law Clinic in New Orleans, took the Harvard research and analyzed what it meant for Louisiana specifically. Compared to the U.S. as a whole, Louisiana had above-average PM 2.5 pollution from 2000 to 2016. The state also has above-average COVID-19 death rates, particularly in the southeastern industrial region. Synthesizing that data, Terrell found that eight of the 10 Louisiana parishes with the highest COVID-19 death rates are in what she calls southeastern Louisiana’s “PM 2.5 corridor” stretching from the coast to New Orleans and along the Mississippi River to Baton Rouge. A former center for sugar cane plantations, the area is now crowded with refineries and petrochemical plants and has been dubbed “Cancer Alley” because residents suffer disproportionately from the disease. The BP oil spill was yet another source of air pollution across South Louisiana, with research showing it caused levels of both PM 2.5 and cancer-causing benzene to exceed health standards in parishes near the coast.

This slide from a presentation by Kimberly Terrell, director of community outreach for the Tulane Environmental Law Clinic in New Orleans, shows the relationship between PM 2.5 pollution (red signifies above-average levels from 2006 to 2015) and the relative COVID-19 death rate (circles) in Louisiana. Both PM 2.5 pollution and COVID-19 deaths are concentrated in the industrial corridor between New Orleans and Baton Rouge known as “Cancer Alley,” where many communities are majority-black.

Terrell’s analysis also showed that Louisiana’s air quality had improved dramatically from 2000 to 2015 but is now worsening. In a recent press call about her research organized by the Louisiana Bucket Brigade, an environmental justice group based in New Orleans, she pointed to a wave of industrialization over the last several years in southeastern Louisiana under the administration of Gov. John Bel Edwards, a Democrat who environmental advocates view as too cozy with the state’s politically powerful oil and gas industry, which has contributed over $350,000 to his campaign since his first gubernatorial run in 2015.

For example, residents of St. John the Baptist and St. James parishes, which sit across the Mississippi from each other along Cancer Alley, have been trying to meet with Edwards to talk about the state’s plans to allow more petrochemical facilities in their already heavily-industrialized communities, but they say the governor has refused. St. John the Baptist Parish currently has Louisiana’s highest COVID-19 death rate, with St. James in third place after Orleans Parish. The population in all three of those parishes is majority African-American, and many residents are also suffering from underlying conditions such as diabetes that worsen COVID-19 — conditions that in turn have been linked to hormone-disrupting pollutants such as dioxins that are emitted by the refineries and chemical manufacturing plants.

“People are dying, people are sick,” said Sharon Lavigne, an activist with the faith-based community group RISE St. James, which is working to stop the industrial expansion. “So many are testing positive with this virus.”

‘A colossal mistake’

But even amid the pandemic and mounting deaths, the Trump administration announced it was rejecting a plan to more strictly regulate PM 2.5 pollution — and an oil and gas industry lobby group that includes BP as a member cheered the decision.

Last week, Environmental Protection Agency Secretary Andrew Wheeler said his agency would not impose tighter controls on PM 2.5 emissions and instead stick with the standard adopted in 2012, which the EPA’s own scientists estimate is associated with some 45,000 deaths per year. The stricter rule had been working its way through the regulatory system for months, but Wheeler — who previously worked as a lobbyist for the Ohio-based private coal giant Murray Energy — said he thought the scientific evidence was not sufficient to toughen existing standards, though he acknowledged that his agency had not considered the Harvard findings on how PM 2.5 worsens COVID-19. There will be a 60-day public comment period on the proposed PM 2.5 standard once it’s published in the Federal Register before the rule goes back to the White House for review and finalization.

In response, 13 Democratic U.S. senators led by Maggie Hassan of New Hampshire wrote a letter to Wheeler noting that the EPA’s own scientists say maintaining the current standard fails to protect public health. “The Environmental Protection Agency should be taking actions that will further protect health during this crisis, not put more Americans at risk,” they wrote. They also demanded answers to several questions, including, “How will this link between air quality and COVID-19 patient outcomes impact future EPA decision-making?” Neither of Louisiana’s senators — Bill Cassidy and John Kennedy, both Republicans — signed on to the letter, nor did any other senators representing Southern states.

Richard Lazarus, a professor of environmental law at Harvard, told the New York Times that the EPA’s timing of its decision was “unbelievable” and “seems like a colossal mistake on the administration’s part.” Not surprisingly, the American Petroleum Institute (API) — a lobbying group whose members include BP America — praised the Trump administration’s move, calling it “a smart balance” that will “help protect public health while meeting America’s energy needs.” API has long fought more stringent PM 2.5 standards, and last November it was part of a coalition of industrial groups that submitted a comment on EPA’s proposed stricter standard that claimed there was “significant uncertainty” about the link between PM 2.5 and public health. Over the last decade, the oil and gas industry has spent $1.2 billion on lobbying at the federal level.

But while it’s working behind the scenes with other oil and gas industry players for lenient regulations that will cause more people to die in the pandemic, BP is portraying itself as a COVID-19 hero, spotlighting its involvement in a White House consortium aimed at tackling the virus that was formed in March by the president’s Office of Science and Technology Policy, the U.S. Department of Energy, and IBM. BP will provide COVID-19 researchers with access to its Center for High-Performance Computing in Houston, where it has one of the world’s largest supercomputers for commercial research. BP normally uses it to crunch geophysical data and says it hopes it can help scientists arrive more quickly at answers about COVID-19.

“We’re all in this together and BP is working with governments and communities to do everything we can to help fight this pandemic,” said David Eyton, BP’s executive vice president of innovation and engineering.

This article was originally published by Facing South.