In their 40 years as Ithacans, James and Janice Turner have worked to reshape a campus, a community and a culture.

By Kara Cusolito, Ithaca Times —

In their 40 years as Ithacans, James and Janice Turner have worked to reshape a campus, a community and a culture.

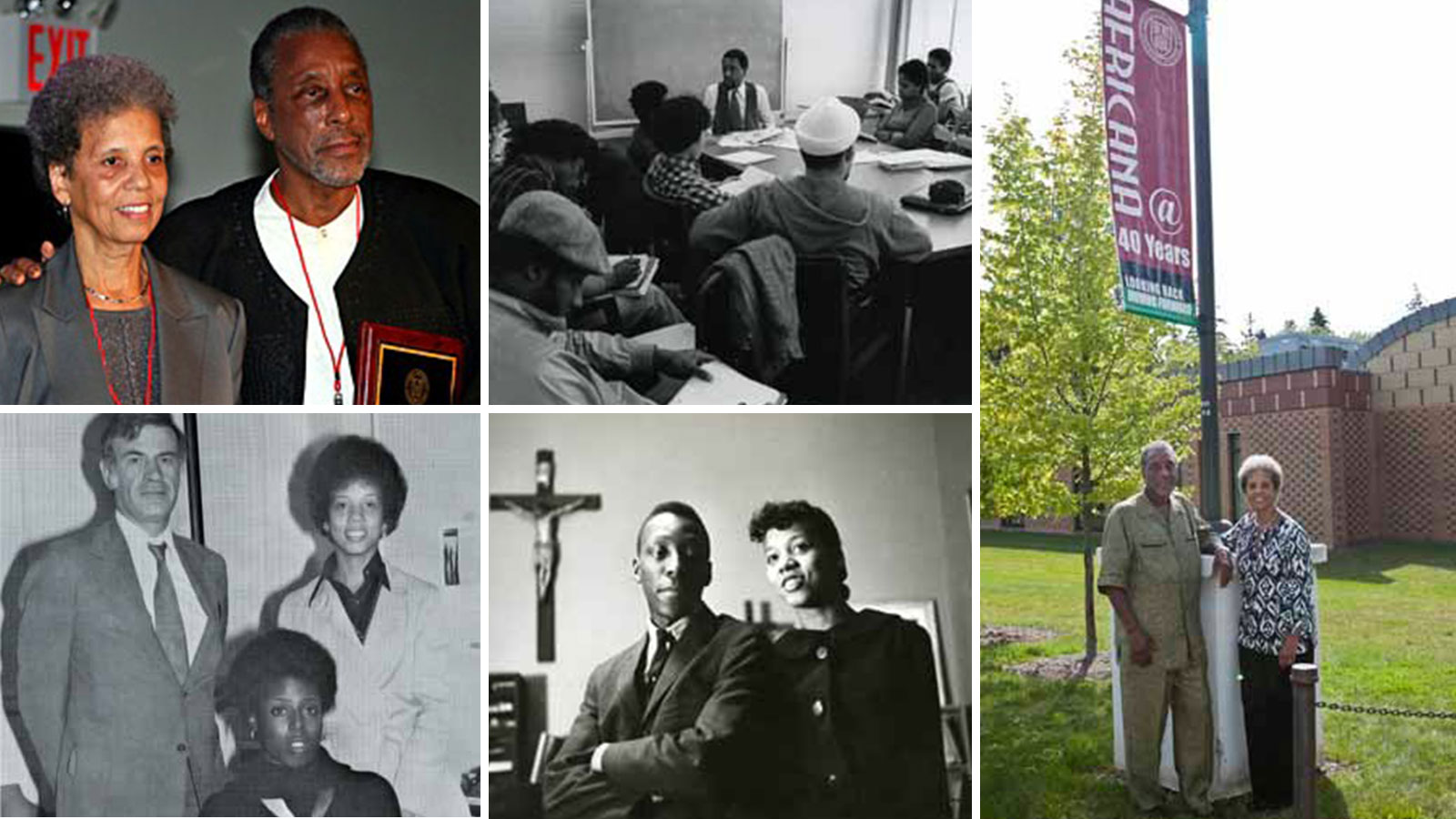

James and Janice Turner pose for a recent photo in front of the

Africana Studies and Research Center at Cornell University.

James Turner, founding director of the Africana Studies and Research Center, and wife Janice Turner, retired associate dean of the College of Arts and Science, came to Ithaca in 1969, at a time when there no black teachers in the Ithaca City School District, only a handful of black tenured professors and no courses in African-American history, life, culture or literature.

“We had to begin the process of changing that environment,” James said.

Though retired on paper, both James and Janice fill their days with meetings and volunteer gigs.

“It’s like we never retired,” James said with a smile and a laugh.

Four decades after their arrival, the couple is often celebrated for their contributions to Cornell and to the city. In September, the couple was honored at a downtown event for their contributions to the community. Last year, the Cornell Black Alumni Association announced a scholarship named in their honor.

In addition to being the founding director the Africana Studies and Research Center – developing its curriculum and growth – James served on the Board of Directors at Southside Community Center, and was the chair of the Tompkins County Human Rights Commission. He’s also worked with the Multicultural Resource Center and the Village at Ithaca.

Janice worked at Ithaca College’s Educational Opportunity Program, and later became associate dean in Cornell University’s College of Arts and Sciences. She was also a mentor to pre-med students, and was and remains involved in the Black Biomedical Technical Association, which was started by the class of 1973.

Janice continues to be committed to education on campus and in the greater community. She spoke of her concerns that while there are so many colleges and universities in the region, there are still so many young people not going to college.

“It’s unacceptable,” she said. “We need more advocates from the community. It’s a very small town; why isn’t every child given the opportunity to go on to higher ed?”

Many of the same issues exist now in Ithaca, Janice said, as existed when they arrived 40 years ago.

“We often hear the same problems and concerns,” she said. “There are a lot of young people not finishing high school and few holding significant jobs in the community.”

James’s work inspired the Village at Ithaca’s equity report card – a study of equity issues within the Ithaca City School District – which former ICSD board member Jeff Furman works on. Furman, a colleague of the Turners, said the couple’s accomplishments are much more than just a laundry list.

“They’ve always been there, supporting community efforts in a very deep and meaningful way,” he said.

Turner’s work and his hands-on support helped improve many of the issues that prompted him to run for school board in the first place, Furman said. The Turners have been integral in promoting equity within the school district, he added.

According to Furman, hundreds of educators and students were impacted by his course with Don Barr at Cornell, “Racism in American Society.” Roberta Wallit, an ICSD teacher who took Turner and Barr’s course, said the class had a profound affect on her and on others who took it.

“Dr. Turner is an inspiring teacher whose commitment to social change has affected a multitude of students, both educators and Africana students, who leave his classes ready to make a positive difference in the world,” Wallit said. “Unlike so many of his colleagues, who have remained up on the hill, Dr. Turner has been invested in the well being of the Ithaca community and has contributed his time and energy to the efforts of those working for equity in the ICSD and the Ithaca community.”

The Turners relocated to Ithaca from Evanston, Ill., in 1969, where James was a graduate student and Janice was the director of a Head Start program for a local school district.

With two of their three children starting out in the city’s school district, Janice began teaching remedial math and reading classes, and James worked to link his students at Cornell with the local school district and downtown recreational programs.

“When we came, we observed that there were no black teachers is the whole ICSD,” he said. “We wanted to improve that.”

Turner arranged partnerships with his students and the downtown community. If he had students interested in child psychology, development, or education, they could work with local agencies like the Greater Ithaca Activities Center or Southside Community Center.

The family decided early on that because their children had grown up in an environment where they were the vast minority, it was important for their cultural grounding that they attend college in a place where that wasn’t the case. So their three children attended Morehouse College, Spelman College and Howard University.

Cornell was not alone in starting an Africana Center that year; there were many other institutions of higher education starting up programs: University of California at Berkeley, San Francisco State University, Ohio State, University of Chicago, Northwestern, Emory University, Syracuse University and University of Massachusetts. That group of universities, James said, worked as somewhat of a support network for one another and to create cohesive pedagogical plans.

“We were the first generation of Africana studies,” he said, adding that it was particularly important to him, because so few students at that time had ever had the experience of a black professor.

This start-up of programs dedicated to Africana studies, a term that was actually coined by James, led to a reshaping of an entire culture, the couple said. In particular, he said, Africana studies opened the door for disciplines like women’s studies, Latino studies and gay studies.

In his early years, Turner was met with both support and resistance. It was not uncommon to face people who blatantly criticized starting up a program for the Africana studies discipline.

“People would say, ‘there is no black culture, there is no black literature,’ so how will you teach a course on it?” James said, adding that argument held no water because there was vibrant culture – it just wasn’t being taught.

In 1970, the Wait Avenue building that housed the original center was burnt down in an act of arson. Still, much of the university was supportive of idea of an Africana Center. The idea for the center stemmed from student and faculty demand, the Turners said, and was the spawn of the historic 33-hour standoff between Cornell University and the African American students who led a takeover of Willard Straight Hall as a result of campus-wide racial tension.

“We got here at a very opportune moment in the history of Cornell, at a crossroads in the history of the country,” James said. “At that moment, many took off school, left, and put their own ambitions on hold because of their commitment to the larger issue of human rights for black people, to continue the unfinished process of the civil war.”

There’s still a lot of work to be done in his discipline, Turner said.

“A lot of people think we live in a post-racial society,” James said. “But segregation still exists; look at certain neighborhoods.”

He noted that having a black president doesn’t mean racial tensions are over, any more than having a female prime minister in other countries has made women completely equal to men, James said. And in more recent years, the concept of diversity has been used to deflect attention from racial equality, he said.

“Now, diversity has trumped racial equality,” he said. “There are still an unequal number of African American students at Cornell University.”

The problem – the difference – James said, is that the proportions are off. While there may be a greater diversity in students’ backgrounds than there was just a few decades or years ago, the population still don’t reflect the actual percentages that exist in the greater population.

It’s quite an undertaking to describe the impact both Turners have had, said Eric Acree, librarian at the Africana Center. Fort and Furman agreed with the sentiment.

“Anything I say will be incomplete,” Acree said.

He said the impact both Turners have had on thousands of students, generations of students, is hard to describe. He himself experienced James Turner as a professor this summer while taking a course with him for the first time.

“The amount of knowledge he has is incredible,” Acree said of his mentor and colleague.

Marica Fort, executive director of the Greater Ithaca Activities Center, said she’s known both Turners for years, and that it’s hard to describe the impact the couple has had on the community and the world.

She said they’ve given support in many ways; everything from attending events, to volunteering their time on boards, to giving financial support that allows young people to further their education. Fort said their devotion to the community and willingness to come off the hill is a special thing.

“You’re just as likely to see them on campus as you are to see them in their office or at events downtown,” she said.

Furman expressed a similar sentiment.

“If we had more Turners, we’d have fewer town-gown issues,” Furman said.

“They’re quiet heroes,” Fort added.

Source: Ithaca Times