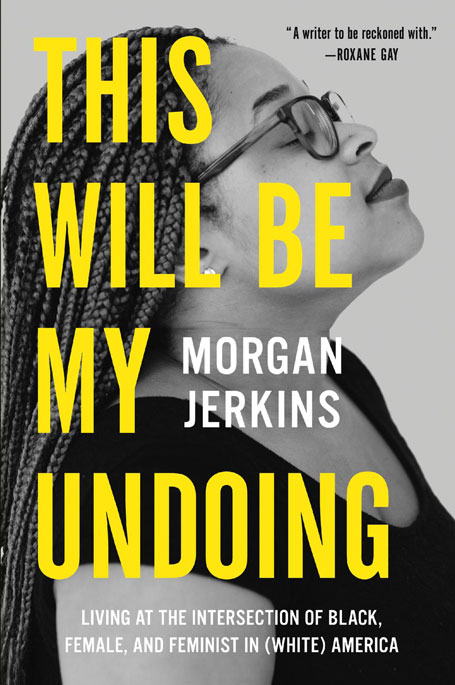

Jerkins talks about her insightful new essay collection ‘This Will Be My Undoing.’

When Morgan Jerkins entered Princeton University at age 19, she felt that she had “made it to a place I was never supposed to be.” As a young black woman, she was a minority on campus, where fewer than 6 percent of the total population is black. In her piercing debut essay collection, This Will Be My Undoing: Living at the Intersection of Black, Female, and Feminist in (White) America, Jerkins marinates on this “otherness,” exploring how she’s come to understand her place as a black woman and a human being––synonymous terms that aren’t always viewed that way.

In her essays, Jerkins is equally critical of the social structures in place to erase the black narrative and the pressures from within black communities to ensure that their daughters conform to white ideals—often through physical means, like the arduous process of hair straightening. She also doesn’t shy away from exploring different experiences of blackness—or wrestling with the ways the black experience is unique from those of non-white women of color.

I spoke with Jerkins on the phone as she was driving home to her apartment in Harlem. Our conversation’s been edited for length and clarity.

VICE: What did you mean when you titled this collection This Will Be My Undoing?

VICE: What did you mean when you titled this collection This Will Be My Undoing?

Morgan Jerkins: I spend a lot of time online—my career started through freelancing—and a lot of exchanges, especially on Twitter, would be about “unlearning.” So many other words start with “un.” I gravitated toward that word because the book goes from when I’m a young girl to a young woman, and I’m unpacking narratives I’ve had about myself and other people, and how they demonstrate racial and gender conflict. I didn’t want it to be seen as too ominous.

In the collection, you discuss the messages black women send to their daughters. Can you talk about these messages from your own experience?

Mothers often advise their daughters that if they are too bossy, self-assured, and opinionated, it’ll be hard to find a husband. That admonition becomes more loaded when you’re a black woman. You get these signals from the world at large that you are the least desirable and very unmarriageable. Those people might have the best intentions, but they want you to try to fix yourself over and over again for someone else’s comfort. They don’t ask, “Why can’t someone else fix themselves to be with you?”

What do you mean when you say black girls are “under surveillance” by the community?

Black girls are sexualized very early in life. There’s a term “fast-tailed girl,” which is a form of slut-shaming, but it’s directed toward a black girl. There’s no equivalent for black boys and men—it’s about, “How is this black girl getting too out of line sexually, and how do we control that?”

You write about an experience where you felt you didn’t feel at liberty to engage in the same kind of activity available to white women.

When you think of pop culture and coming-of-age TV shows, it’s not rare that you find a white female character experimenting with drugs and alcohol—but you rarely see black girls experimenting with drugs. We’re all taught that drugs are bad, but in terms of what we see visually black girls are taught that you aren’t respected or acknowledged from the moment you walk in the door. You have to make sure you look a certain way, dress a certain way, act a certain way. You don’t start off with a clean slate, so you can’t go out of bounds––even if you want to.

The book’s opening essay is about your desire to earn a spot on the cheerleading team at school. You write that you wanted to be “swallowed up” in a white identity. How do young black girls begin to make sense of their own identity?

I knew that I was different from other girls—I could see it in our hair, our dialect, our music. But I knew I wanted to be seen as beautiful not just by my community, but by everyone. I equated beauty with white girlhood. In high school and middle school, the people who are popular are white cheerleaders. I wanted to assimilate. I wanted to be absorbed by them. I wasn’t confident in my identity.

It was one of the most difficult essays I’ve had to write because it was so painful. It was at that moment where someone used my identity against me in a dehumanizing way. The validation I was seeking was not just from the cheerleading squad. It was because I wanted to be acknowledged by them in the way that I’m always conscious of who they are. White girls in my school could see reflections of themselves in the squad. I didn’t. That’s the difference.

You write that the black female body is a “target for destruction.” Talk about this concept and what it means to you personally.

Violence is not just physical. Microaggressions are a type of violence. It’s a short, trivial moment, and even if the person is well-intentioned, it puts stress under you. People of color can be under stress for generations because of these traumas. It’s also about the way we’re treated in the media and pop culture. We’re often ignored, erased, made fun of. Serena Williams––how many times has she been compared to an animal?

It’s not always the physical violence. We could talk about street harassment, domestic violence. But it’s violence that comes from other ways––ways that try to make sure black women don’t exist. That we don’t have to be aware of them. I wrote about an experience I had with an adviser’s family who asked why I call myself a black woman. He wondered why don’t just call myself a human. It was as if being called a black woman is not human. That felt like a form of violence. It put me under great stress. You see that people don’t understand, but you think: Is that my issue? Why do people need to compartmentalize me to understand me?

Words we use to describe race can be powerful. Can you talk about what terms like

“black” and “brown” mean to you?

If a black girl wants to define herself as brown, that’s fine. But we should ask: Why we would call ourselves brown? I read criticism of a film called Girlhood by a black girl who asked why we black girls call ourselves brown, when it’s a dilution of blackness? It’s a good question. It should be considered when we think about these identifications.

Class also plays into conversations about race. How does your background influence your story?

I’m not the resolution. Black women are not a monolith. But there are privileges I do have. When I talk about going to an Ivy League school, the way I look, my socioeconomic status––that matters. My experience as a woman who grew up in suburban New Jersey is not the same as someone who grew up in the Mississippi Delta. I have to acknowledge that. If I don’t, I reinforce the fallacy of a single story.

You write that Beyoncé is a divisive figure. How do you see that happening?

She’s mainly divisive between black and nonblack audiences. When she was announcing her pregnancy, I saw stories that said “it’s not that big of a deal.” Actually, it is. If you look at how many black mothers die in childbirth, it is a big deal. It’s OK to celebrate that. When I think about Lemonade and how many times people wanted to diminish what its impact is, particularly for black women, that’s when it’s divisive. She’s important, but the way she’s covered in the media shows that she’s divisive.

How does feminism leave black women out? How should it look instead?

Listen to black women. Include them when you have conversations about sexual harassment, the pay wage gap, and reproductive health issues. Don’t put them as an afterthought. White women are usually at the forefront, and if women of color are included, they’re in the background. They need to be in the forefront. Feminism cannot last or sustain itself if it just prides itself on white women.

Are black women invisible in the #MeToo movement?

The #MeToo movement was started by a black woman, years ago. But we need to get different stories out there. There’s a spectrum of pain that men can inflict on women that all fall under rape culture. I hope it keeps unfolding, and we keep talking about how race adds a layer to them.

Who can tell the stories of black people? Does the intention behind it matter? Can a white person fairly represent black lives? If not, how should this be done?

It’s hard. I’ve spent a lot of time online, and you hear black women say, “I do not want anybody but black women to write about black women.” They have a point. There’s such a disconnect between communities of color and journalists and critics, and what can be said, and how things can be misconstrued and messed up.

But at the same time, I think, Is that too radical? If a black woman publishes something I don’t like, does the same rule apply? When I think of who should write us, it depends on the situation and the context. I personally don’t believe that someone who is not black can’t write about black women. It’s too radical of a jump.

When I think about exploiting black women, we need to have to be very careful with black pain and black trauma and how it is often used as a crutch for critical thinking. When I saw Orange Is the New Black, it was so hard to get through. It gutted me. But when I found out that there were no black writers in the writing room, it made me feel a certain way. There were so many black women in the series, so much violence being committed to them, but there’s no black women in the room? That unevenness is what I want to address.

If you wanted to send a message to white writers and critics about how to better listen to and understand black voices, what would you say?

Include them and compensate them properly. It’s not enough to say, “Come in the room and tell us about yourself.” Give black writers the space to do the work they want to do. Make sure there’s mentorship in order. Listen to their perspective. Pay them accordingly, as you would your white colleagues. You need to help make sure these people are sustained.

Personally, I’d like to see more male voices to rise up and support women when it comes to the current conversations around harassment and abuse. Is there a parallel here for you as a black women? Do you want white allies?

For the women’s movement, I want to hear men [talk] about how they can do better. It’s usually men trying to gaslight women, or say the experiences weren’t that bad. When white people speak about racism, I think––How can they speak on that? There are all of these structural barriers at work. White people need to talk about it as a reckoning. Not in a way that tramples on the people who experience racism firsthand.

You write that when it comes to some form of abuse from black men, black women are often placed in a difficult situation––wanting to protect themselves while still remaining loyal to black men, who are unfairly targeted by the law. Can you talk about how black women grapple with this?

I’m talking about street harassment, but you can use Bill Cosby as an example. When we have these conversations of sexual harassment or rape, a lot of the time, black women feel like they have to choose between their blackness or their womanhood. The problem I have is the compartmentalization that is unfair to us. Black women are conditioned to be pillars of the community. Who will take care of us when we’re weak? We’re conditioned to protect everyone, even at the expense of ourselves.

Follow Hope Reese on Twitter.