By Nick Mirzoeff, Hyperallergic —

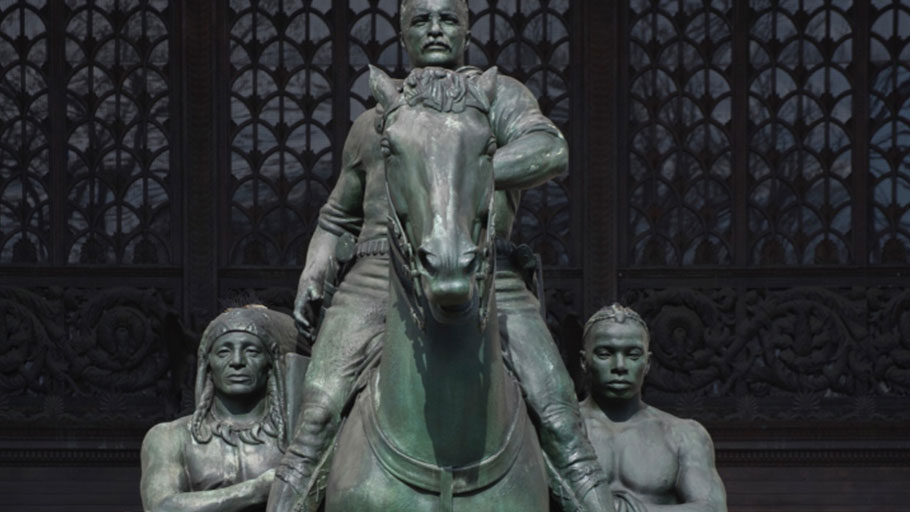

Almost two years after the 2017 fascist rally at Charlottesville around a mediocre statue of Robert E. Lee, the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH) opened its exhibition Addressing the Statue for an unspecified run. The statue in question is James Earle Fraser’s massive “Theodore Roosevelt Equestrian Memorial,” situated outside the Museum’s main entrance, depicting Roosevelt flanked by his gun carriers, a stereotyped Plains Indian and a generic African.

It wasn’t the museum’s fault that another “replacement theory” white supremacist, like those at Charlottesville, carried out terrorist attacks in El Paso just a few days later. But it wasn’t unconnected either. From hate groups like Identity Evropa to Trump’s evocation of “beautiful” statues, the classicized statue has become a symbol of White supremacy.

The statue depicts Roosevelt on horseback, with a Native American man and an African man on foot on each side. It originally intended to celebrate Roosevelt as a devoted conservationist and author of works on natural history. But today many see a racial hierarchy in its composition (©AMNH/D. Finnin).

In this moment, what does it mean to “address” the Roosevelt statue? In poet Claudia Rankine’s Citizen, the narrator attends a lecture by the philosopher Judith Butler, who is asked why words are hurtful: “Our very being exposes us to the address of another, she answers. We suffer from the condition of being addressable.” The narrator observes: “After considering Butler’s remarks, you begin to understand yourself as rendered hypervisible in the face of such language acts.”

The racist murder of Heather Heyer at Charlottesville made it clear that Confederate statues are such speech acts — and hate speech at that. Their address in public space makes people vulnerable, albeit unevenly and unequally so. In response, cities like New Orleans and Memphis took down at least some of their Confederate statues. Nationwide only some 60 statues out of a total of over 700 were removed.

In liberal New York City, Mayor Bill de Blasio cautiously set up an advisory commission to review its monuments, including Roosevelt. Its subsequent report in January 2018 split on Roosevelt, calling for an “additive” approach: meaning both contextualizing work at existing monuments, and adding new monuments, like that for Shirley Chisholm. De Blasio has sided with that approach, a metonym for liberalism: small-bore, negotiated, additive projects, rather than systemic change.

The first fruits of this policy are now on view at Addressing The Statue. It’s hard to review as an exhibition. The show covers the walls of a corridor leading from the African mammals hall to the museum shop with text and a screen displaying a 15-minute video commissioned from African-American writer Reniqua Allen. There are no actual artifacts, although there are some interesting copies of archival materials from the James Earle and Laura Gardin Fraser Papers at Syracuse University and the AMNH’s own archive. What predominates is text, in Twitter-length bubbles down the corridor.

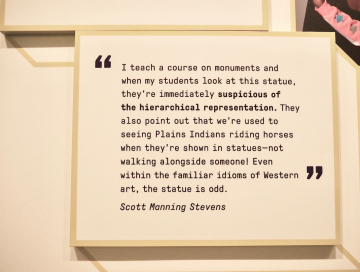

Quotation of Scott Manning Stevens in the Addressing the Statue exhibition (photo by the author)

Viewers are supposed to make up their own minds after reading all this but AMNH has already decided. Curator David Hurst Thomas, from the AMNH Division of Anthropology, declares: “some today view the statue as heroic. Others see the statue as a blatant symbol of racial hierarchy. Addressing the Statue sidesteps such simplistic binary thinking in favor of multiple perspectives and multiple voices.”

In 1990s academia, this approach was known as “teaching the conflicts.” And sure enough, a New York Times review praised the show for “balance.” But it’s the “balance” of news media — always offering “both sides” — rather than the balanced judgment of the historian that’s on view.

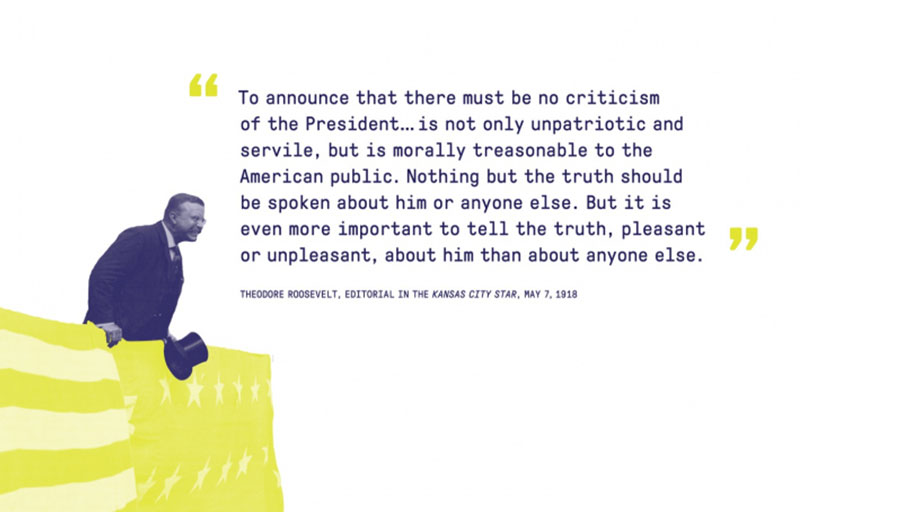

For example, the exhibition balances Roosevelt as both a racist and the host of African-American leader Booker T. Washington at the White House. Does this in fact constitute a balance, that is, are these conflicting worldviews of equal validity or weight? A recent New York Times op-ed noted that racism was “central to Roosevelt’s vision for America, and not just an artifact of his time and place.” Indeed, he gets an entire chapter in Princeton professor Nell Irvin Painter’s History of White People. There’s no mention at AMNH of his support for eugenics or his 1905 speech that popularized the supposed threat of “race suicide.”

The bronze equestrian statue of U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt (1858-1919), which stands on the Central Park West entry plaza to the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH), is the focus of a new exhibition, Addressing the Statue, that opened July 16 at the museum; pictured in the Akeley gallery (©AMNH).

Together with a range of other eugenic “theories” (which have long since been discredited but are once again circulating), such ideas motivated the severe immigration restrictions of the early 20th century and set the ground for eugenic sterilization. Today, they are the origin of the “replacement theory” now motivating White supremacy worldwide.

Can a viewer properly address this statue when AMNH has so framed the project? From my observations, most visitors walked through without stopping. Several used the large-scale photograph of the statue as a selfie opportunity. A minority spent time reading their way through in a very noisy location. I noticed two custodians watching the video. When I asked for their opinion, I was told they had been instructed not to talk about it.

The exhibition largely rehearses the arguments of the mayor’s commission, voiced through two commission members: Harriet Senie, a CUNY art historian against removal, and Columbia’s Mabel Wilson, a professor of architecture and African American studies, for removal. Other thoughts come from academics and museum professionals, including two Indigenous academics, Scott Stephen Mannings (Akwesasne Mohawk) and Philip Deloria (Dakota descent), and a variety of visitors to the statue (no indications as to how they were selected or what questions were used to solicit the posted responses). The protestors are given voice through NYU’s Andrew Ross, who is part of Decolonize This Place — in short, multiple perspectives.

But this is not a thorough address. To take just a few examples, curator Thomas suggests that the statue is displayed at the museum by choice of New York State. True. But then-Museum director Henry Fairfield Osborn (a promoter of eugenics and immigration restrictions) waged a five-year campaign to get it and defeat those who wanted it upstate. Unstated is that the cost to the city was $3.5 million (about $60 million in today’s money), meaning that the people own the monument, not the Museum of Natural History.

The statue depicts Roosevelt on horseback, with a Native American man and an African man on foot on each side. It originally intended to celebrate Roosevelt as a devoted conservationist and author of works on natural history. But today many see a racial hierarchy in its composition (©AMNH/D. Finnin).

Again, the show points out that AMNH hosted the Third International Congress of Eugenics in 1932, just four years before the memorial was opened. A photograph of George Washington’s genealogy from the accompanying exhibition is on display to illustrate the point. Wouldn’t it have been more pertinent to show that of Theodore Roosevelt, complete with portrait bust, also in the 1932 exhibition? Here and throughout this show, racism is disposed of as a “discredited” side effect of a past time. If only.

Finally, the outsize form of the statue noted by all was a result of Osborn’s long-held plan to create a grand easterly approach to the memorial across Central Park, an idea scotched by Robert Moses. One reason for these oversights may be that, despite the wealth of scholarly attention paid to AMNH itself, there is hardly any scholarly literature focused on the Roosevelt statue, undermining claims for its significance as a work of art.

Let’s address the statue. Why do so many people see it as signifying a “racial hierarchy,” leading to protests every decade the statue has been up? All the members of the public quoted find the statue racist, although they take different positions about removal. Even the museum’s own materials for the exhibition use the term “racial hierarchy.” The statue makes a simple visual distinction: Roosevelt is massive and on horseback, dominating the African and Native figures. Most importantly, the children interviewed get that. And it’s through such visual shocks that racism is learned.

The bronze equestrian statue of U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt (1858-1919), which stands on the Central Park West entry plaza to the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH), is the focus of a new exhibition, Addressing the Statue, that opened July 16 at the museum; pictured in the Akeley gallery (©AMNH/C. Chesek)

While Osborn oversaw the memorial project, his goal for AMNH as a whole was to become “a speechless university” using “visual or direct education.” He deeply believed in racial hierarchy and made it visible across the museum. Are we to assume that the monument in which he invested 15 years of struggle was somehow exempt? When the statue was made, it was widely believed that there were three major racial groups: Caucasian, Mongoloid, and Negroid, hierarchically arranged in that order. The statue clearly visualizes that racist view. In short, to use today’s jargon, what you see is what you get.

Some exhibition participants go to great lengths to transform this visible “racial hierarchy” into allegory. Harriet Senie asserts that all the statues in the Theodore Roosevelt Equestrian Memorial are “heroic … allegorical figures,” basing her claim on sculptor James Earle Fraser’s comment in the 1940 press release for the unveiling: “The two figures at [Roosevelt’s] side are guides symbolizing the continents of Africa and America, and if you choose may stand for Roosevelt’s friendliness to all races.” Only, the press release omitted the phrase in italics. What Fraser actually said appears to be a response to a suggestion made to him, even as it makes clear that the figures depict guides and not heroes. As for “friendliness,” all eugenics denied prejudice, as Trump does today, claiming merely to address the facts of nature.

If the supporting statues symbolize their respective continents, what was the allegory being suggested? An allegory requires a meaning that the viewer needs to construct. The most obvious available meaning is that of racialized hierarchy. That’s still visible today. But no one wanted to see it in 1940. The Second World War against Nazi Germany was under way. At the unveiling ceremony, far from dwelling on Roosevelt, keynote speaker Greville Clark warned the United States to prepare for war. It was not the time to address the statue’s racial hierarchy or the AMNH’s recent enthusiasm for eugenics, so notably adopted by Nazi Germany.

Imagine a visitor entering the museum in 1940 past the Roosevelt statue. In the lobby, they would have seen eugenicist sculptor and taxidermist extraordinaire Carl Akeley’s stereotyped bronze group of “primitive” “Nandi Spear Men” (sculpted from African-American models) facing a group of lions; then they might look up to see William Andrew Mackay’s mural of Roosevelt on safari in Africa, beginning with the figure of Ham, son of Noah, described by the AMNH in 1944 as “cursed by his father and destined with his son and all his descendants to perpetual slavery”; and finally they would enter the Roosevelt Hall of African Mammals (as it then was called) and be confronted in the gloom with Akeley’s array of charging elephants. Osborn went to great lengths to ensure that the Africa mural was placed over the door to the Hall of African Mammals, over opposition from city officials.

It beggars belief that Osborn, an admirer of Hitler and so racist that he denied humanity had its origin in Africa, intended this “visual education” to celebrate Africa as “heroic,” rather than as a “primitive” world, whose fauna were thought to be on the verge of extinction. Not much has changed. The elephants are now sponsored by climate change denier Rebekah Mercer, member of the AMNH Board of Trustees, alongside Theodore Roosevelt IV.

I did speak to those few visitors who stopped to look at the show during the hours I was there. Most were out-of-town tourists and none had intended to visit it, except a Columbia University seminar group. Museum administrators would be pleased by the response on the whole. Many White visitors spoke unprompted of the dangers of “erasing history,” while also being disturbed by Roosevelt’s racism to Indians. That said, a Nigerian visitor was unimpressed with the claim that the statue demonstrated racial equality — “bullshit” — while two African-American women from New York were skeptical of the entire video.

Anyone can post a response to the exhibit’s website and, since the replies are bound to be tabulated for PR purposes, I would encourage everyone to do so.

What else is to be done by those of us — including half the mayor’s commission — who do see this monument as representative of a racial hierarchy? Let it firstly be admitted that we lost and this response doesn’t change that. There are art issues and political issues — and they are not separate. Liberalism has long enshrined art as part of its Bildung (cultivation) and so, by extension, any removal or destruction of art must be anti-liberal.

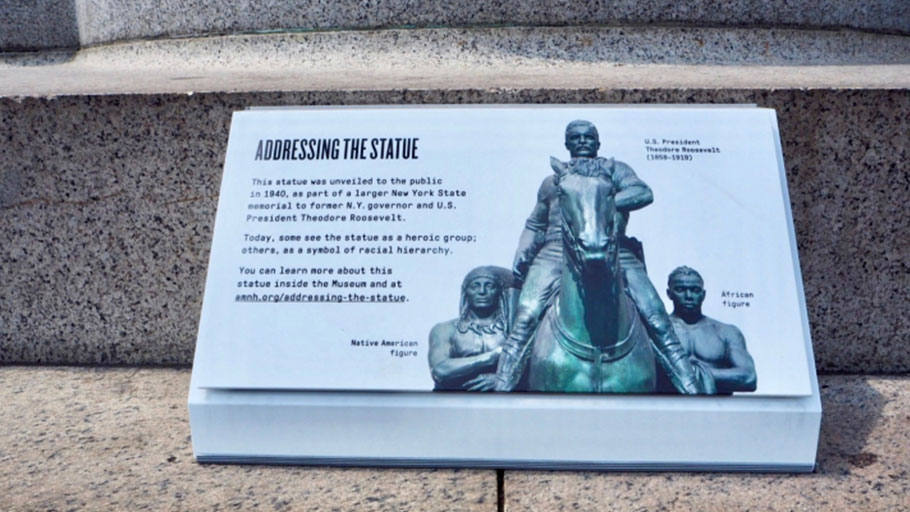

Art writer Aruna d’Souza has shown that when it comes to racism, for fifty years the art world has favored the asking of “difficult questions,” rather than action. AMNH has added some questioning captions to the 1939 diorama inside the Roosevelt Memorial depicting Dutch domination of the Lenape people. Four groups of NYU students studying this installation for my class all concluded that most visitors did not read them. Anecdotal as this evidence is, if a plaque with contextualizing information is placed next to the Roosevelt statue, it’s hard to imagine many stopping to read it in the crush to get in, among the queues for ice-cream and the NYPD crowd control barriers protecting the monument. And none of this gets around the crushing impact of racist depiction at first sight upon entering the museum — just as Henry Fairfield Osborn likely intended.

The plaque currently on view adjacent to the monument at the center of the Addressing the Statue exhibition (photo by the author)

Against those art historians who insist that all monuments must remain standing as part of “history,” it’s time to reassert the active making of historical analysis and understanding as constitutive of the present and future possibility. No one in these United States is about to forget half a millennium of settler colonialism and racial hierarchy. But there is still no museum of racism. The AMNH would be the obvious place to make one.

Against those art historians who insist that all monuments must remain standing as part of “history,” it’s time to reassert the active making of historical analysis and understanding as constitutive of the present and future possibility. No one in these United States is about to forget half a millennium of settler colonialism and racial hierarchy. But there is still no museum of racism. The AMNH would be the obvious place to make one.