The world-spanning art of the Harlem Renaissance.

By Rachel Hunter Himes, The Nation —

In January 1969, the Metropolitan Museum of Art opened an exhibition dedicated to the vibrant history of Harlem—the institution’s first attempt at displaying and interpreting African American culture. “Harlem on My Mind: Cultural Capital of Black America, 1900–1968” came to life at the tail end of the civil rights movement and on the cusp of Black Power.

Enthusiastically promoted by the Met’s then-director, Thomas P.F. Hoving, the show was meant to signal the institution’s commitment to civil rights and the Black political struggle and to bring Black and white audiences together in the celebratory space of the museum. But something was missing—in retrospect, an unthinkable omission. Not a single painting, sketch, or sculpture was on view in the “Harlem on My Mind” galleries. No fine art by Black artists—no fine artwork of any kind, in fact—appeared.

Instead, “Harlem on My Mind” represented Harlem via floor-to-ceiling photomurals, archival ephemera, and street soundscapes alongside interpretive text. It was the cutting edge of immersive exhibition design; the Met had never put on an exhibition like it before (and hasn’t since). Yet from the perspective of many Black artists, critics, academics, and organizers, the show was woefully retrograde. Despite concerns raised by community representatives during the exhibition’s development, the Met had reduced the culture of Harlem to an object of sociological, or even ethnographic, inquiry. Black people were once again the subjects, rather than the authors of their representation.

The museum’s choice was strange, but also telling. By refusing to integrate the art in its galleries, the Met seemed to reject the idea that Black art could be worthy of display and to suggest that Black audiences might prefer flashy spectacle to works of fine art. The show also reflected a persistent trend in the interpretation of the Harlem Renaissance. Too often, the movement has been understood as a historical moment and social phenomenon while its visual art in particular has gone unconsidered, as if it were enough to acknowledge that Black people created art during this period without bothering to inquire into what that art looked like or what it meant.

Today, the legacy of “Harlem on My Mind” lies in the organizing that its failures prompted. In response to the exhibition, artists formed the Black Emergency Cultural Coalition and picketed the show, carrying signs that read “Harlem on Whose Mind?” and “Whose Image of Whom?” The BECC, which remained active through the 1970s, would go on to demand that the Met and other art institutions hire Black curators and administrators and display work by Black artists. It would not be an overstatement to suggest that the new Met show “The Harlem Renaissance and Transatlantic Modernism,” curated by Denise Murrell, is a descendant of this activism. The show is an open-ended exploration of the era’s art, gathering paintings, sculptures, prints, drawings, and photographs by well-known and relatively unknown artists into a vibrant and searching collage that offers us a wide range of views on the Harlem Renaissance’s origins and meanings and the ways the movement found artistic expression. Rather than merely concluding the Met’s Harlem saga by showcasing the artistic variety and vicissitudes of the Harlem Renaissance, this exhibition points us in a thousand new directions for engaging with the art of the period and paves the way for future exhibitions too.

One of the strongest impressions left by “The Harlem Renaissance and Transatlantic Modernism“ is the story it weaves about Black sociality in the 1920s, ’30s, and ’40s. The social spaces that the exhibition makes visible are many and varied—and, noticeably, not all of them are situated in New York City. Black people gather in city streets and in their homes, in bars and dance halls, in jazz clubs and pool halls and beauty salons, at lawn parties and luncheons and formal dinners, and through a variety of associations, professional, fraternal, and sororal. The scenes on view belie any notion of a homogeneous Harlem Renaissance. Instead, we see the movement through a prism, glimpsing the gradations of Black experience and even seeing social groups at odds with one another.

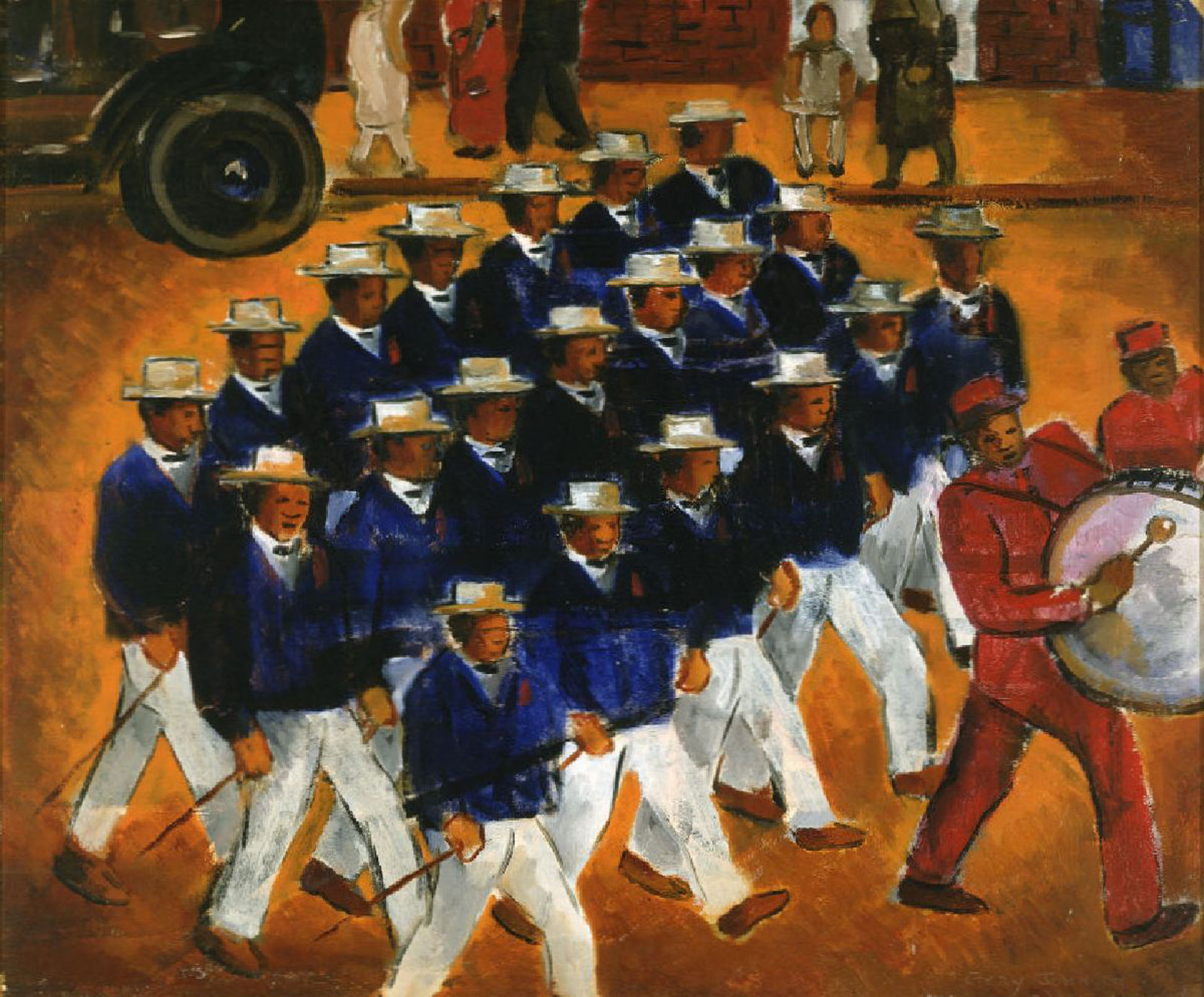

Elks Marching, 1934 by Marvin Gray Johnson

In Elks Marching, a 1934 painting by Malvin Gray Johnson, we witness marchers on parade, boat-hatted and white-trousered Black men in orderly ranks, whose collectivity suggests the cohesive power of Harlem’s fraternal orders. In contrast, the dancers in Palmer Hayden’s 1943 Beale Street Blues, an unruly composition of clashing patterns and shifting viewpoints, move to an entirely different rhythm. And in James Van Der Zee’s 1927 photograph Luncheon Party—in which finely dressed women pose around an elegant table setting gleaming with middle-class respectability—we see a very different Harlem Renaissance than we do in Archibald J. Motley Jr.’s 1936 painting The Liar, in which a set of men gather in a windowless back room to shoot pool, smoke cigarettes, and drink whiskey on the rocks.

The differences between Motley’s pool shooters and Van Der Zee’s bourgeois diners mark out just some of the varieties of Harlem life in the 1920s to the 1940s. Van Der Zee’s photographs are celebrated for democratizing the possibility of representation and for bringing portraiture to an ascendant Black middle class. Yet they also crafted a very specific image of Blackness. The equally stylish subjects of Motley’s painting offered another: They let it all hang out. Smoking, dancing, and drinking, strolling and laughing, Motley’s Black subjects convey nothing so much as ease and enjoyment.

Yet to some, certain features of Motley’s paintings—the gleam of bright eyes against rich dark skin, thick lips parting to reveal white teeth, the artist’s consistent interest in “typical” nightlife scenes—have seemed to verge on caricature. Is this ironic? Are Motley’s paintings a (very) early form of pop art, digesting the tropes of popular entertainment? Did Black viewers see themselves in this work, or did white audiences eagerly consume these scenes? Perhaps these questions are beside the point. In 1926, Langston Hughes wrote: “We younger Negro artists who create now intend to express our individual dark-skinned selves without fear or shame. If white people are pleased we are glad. If they are not, it doesn’t matter. We know we are beautiful. And ugly too…. If colored people are pleased we are glad. If they are not, their displeasure doesn’t matter either.”

Archibald J. Motley Jr. Blues, 1929

This indifference to the viewer’s probing gaze is reflected in the persistent inward turn of Motley’s compositions. Across his paintings, and perhaps most notably in his lovely Blues of 1929, we see his subjects looking into the painting, gazing at each other rather than back at the viewer. In Blues, we are confronted with a wall of backs: of the members of the orchestra, of men leading smiling partners in dance, of humanity cheek to cheek and mouth to mouth. Although subjects in a painting, they are indifferent to our gaze. There is a sense of warm enclosure, of the scene’s sufficiency unto itself.

The scenes of Black social life on view are not limited to the city blocks of Harlem. Motley, who was born in New Orleans and spent most of his life in Chicago, never lived in New York, despite being celebrated as one of the Harlem Renaissance’s leading artists. The Met exhibition suggests that “Harlem” was more an ethos than a geography; the movement’s “transatlantic modernism” extended far beyond New York and even North America.

One of the Harlem Renaissance’s other capitals was Paris, where an international set of Black artists studied, worked, and socialized. Encounters in that cosmopolitan center are reflected in the works on view—for example, in the lithe deco form of Richmond Barthé’s sculpture of the Senegalese dancer Féral Benga. Barthé, a Mississippi native who traveled to Paris from New York in 1934, was enchanted by the cabaret sensation, who performed alongside Josephine Baker in Paris’s Folies Bergère. Benga, who appears in the nude, is all sinewy elegance. Poised on the balls of his feet, he sweeps the blade from his signature saber dance overhead as he twists at the waist in a gleaming bronze that evokes the hue of his skin.

In Barthé’s sculpture of Benga, we catch sight of a queer Harlem Renaissance—a theme reflected in nearby works, including Dark Rapture, a nude painting of James Baldwin by his dear friend Beauford Delaney, which shimmers with prismatic color. Both gay, Barthé and Benga met amid the artistic ferment of Paris, where the sculptor, like many Black Americans of the time, sought social freedom and artistic inspiration in the city where the dancer, disinherited by his father, made his home after leaving Dakar.

Diasporic pathways like these yielded another of the exhibition’s most compelling portraits. The seated Black man in the Dutch artist Nola Hatterman’s 1930 painting has only recently been identified as Louis—or Lou—Drenthe. An émigré to Amsterdam from Suriname (at the time still a Dutch colonial possession), Drenthe played the trumpet on the city’s jazz scene, joining American acts when they headlined overseas. In this 1930 work, he is natty and urbane in a brown suit jacket, bow tie, and tan trousers, his pose a study in composed self-possession, his expression alert and sensitive yet distant. Although Drenthe worked as a waiter in Amsterdam’s first Surinamese restaurant, here he is pictured instead as the patron of a café whose red gingham tablecloths are refracted in the glass of pale beer at his elbow. (Originally intended as an advertisement for the Amstel brewery, the painting was ultimately rejected by the company.) Trompe l’oeil details—a pair of yellow leather gloves perched at the forefront of the canvas, three coasters bearing the Amstel logo, a crisp newspaper whose legible advertisements may suggest his additional employment as a stage actor—push this painting beyond the realm of conventional portraiture and echo the collage aesthetic of Picasso’s early cubism.

Alain Locke, the chief theorist of the Harlem Renaissance, identified Harlem as the home of the New Negro, the Black man or woman liberated from stereotypes, shaping their own life as they shaped a nascent Black culture. Yet far from New York, Drenthe cuts the figure of the international New Negro.

It is unsurprising that portraiture should dominate in an exhibition dedicated to the exploration and affirmation of modern Black identity. Among the many examples on view, I found myself powerfully drawn to Winold Reiss’s Two Public School Teachers, a pastel drawing of two gray-clad women with luminous features. As in Reiss’s other portraits, including those of Locke and W.E.B. Du Bois (both also on view), careful shading makes the subjects’ face and hands contrast strikingly with their bodies and clothing, which are suggested only by minimal and fluid contour lines.

As I am sure others will, I made the mistake of assuming that Reiss, like his subjects, was Black. I was surprised to learn not only that was he a white German but that this sensitive yet matter-of-fact drawing found itself at the heart of a controversy over representation. Reiss, who often made African American men and women his subjects, had been chosen by Locke to provide illustrations—among them Two Public School Teachers—for an issue of the publication Survey Graphic, which explored Harlem, the “Mecca of the New Negro,” through writing on history, philosophy, sociology, and culture. That issue, which proved successful, would later become the core of the volume The New Negro: An Interpretation, which expanded on Reiss’s illustrations and the essays, poetry, and fiction selected by Locke.

Yet reactions were mixed when the Harlem public encountered Two Public School Teachers in print and in a concurrent exhibition at the 135th Street branch of the New York Public Library (now the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, it was the only place in the city where Reiss’s portraits of Harlemites would be seen during his lifetime). One Black viewer called the two women “forbidding”; another worried that the work might even be a “sinister move to prevent the hiring of Negro teachers.” But Locke responded in no uncertain terms to such criticisms. To his mind, such critics were “Philistines” whose fixation on promoting “favorable” representations suggested a “playing-up to Caucasian type-ideals” and threatened a “truly racial art with the psychological bleach of ‘lily-whitism.'”

Laura Wheeler Waring

The issue of colorism is also taken up in a work by another lesser-known Harlem Renaissance artist brought to light by the Met exhibition, the portraitist Laura Wheeler Waring. Her small painting Mother and Daughter shows two women in profile, tightly compressed within the space of the canvas. Their marked resemblance makes their relationship clear, yet the younger-seeming woman in the foreground is significantly paler, with closely curled red hair and rosy cheeks.

This painting predates Nella Larson’s Passing, a Harlem novel about two women who can “pass” as white, by just two years. Yet while Passing ends with the tragic death of the woman who conceals her background and chooses to “pass,” the message of Waring’s painting is more ambiguous. Is it, we are invited to wonder, a critique of a Black elite for whom racial advancement meant the dilution of physical features perceived as “racial”? Or is it a reflection on feelings of kinship and belonging that transcend color? Waring herself, as her self-portrait (which is also on view) shows, had lighter skin, while many of her subjects—mostly young women—had a variety of skin tones. In one such portrait, an anonymous dark-eyed, dark-haired young woman, with deep brown skin painted like matte velvet, shading into cool umber and faint violet, cradles a pomegranate while looking at us.

Aaron Douglas, from Aspects of Negro Life: From Slavery to Reconstruction, 1934.

In contrast to these singular portrait subjects, the exhibition also invites us to witness the unfolding saga of the collective Black subject of history, as depicted by the painter Aaron Douglas in his monumental Aspects of Negro Life: From Slavery to Reconstruction.

One of the artist’s masterpieces, this New Deal–era painting, commissioned by the Works Progress Administration, has been temporarily taken down from the high walls of the Schomburg Center and brought to eye level. The 11-foot painting is the largest in Douglas’s four-panel series tracing the diasporic journey from Africa to the modern metropolis, where the Black man becomes the urban industrial proletariat. Within this dense and complex composition, figures stooping to pick cotton are awakened by an orator, whose powerful voice is made visible by the concentric circles that radiate from him, producing ever more subtle gradations of hue and tone as they overlap and inflect the artist’s signature silhouetted forms. Broken chains dangle from arms lifted in strength and celebration as uniformed figures take up arms, recalling the critical historical revision of Du Bois’s Black Reconstruction: It was Black people who liberated themselves, stealing back their own labor power from the slaveholding South and rising up to fight those who held them in bondage.

The painting’s composition can be read from right to left, like a text, but its narrative also radiates out from its core and moves from the foreground into the background, where institutions of learning and employment crown a distant hill. While Douglas’s work is often interpreted as straightforwardly documentary, the painting’s interpenetration of forms and bodies and its exploration of different modes of storytelling transcend linear narrative. In Black American history, we see the past unfold in the present.

The exhibition offers many more engagements with Black history and identity. A small and sober section at the show’s end displays explicit artistic engagements with racial violence. Here, one can find Meta Vaux Warrick Fuller’s In Memory of Mary Turner as a Silent Protest Against Mob Violence. Not even two feet high, it is a memorial monument that exists only in painted plaster. Its subject, Mary Turner, was murdered by a lynch mob in 1918. Grasping hands drag at her skirts, yet she rises above them unimpeded, her cradling arms evoking the unborn child who died along with her. This plaster sketch, which despite Fuller’s wishes was never cast in more durable bronze, reminds us that we are just beginning the work of reckoning with and rectifying the violence that scarred 20th-century Black life.

The Met show is only the fourth major museum exhibition to engage the Harlem Renaissance (not counting “Harlem on My Mind”). Beyond its significance in bringing forgotten artists to light and suggesting new approaches, it is a pleasure to experience, a rich tapestry of themes and topics, people and places, perspectives and explorations that reveals the scope and breadth of the Harlem Renaissance. We have HBCUs to thank for their stewardship of many of the revelatory works on view, as well as the descendants of artists like Laura Wheeler Waring, who in the absence of institutional interest preserved their legacies for much of the past century.

One final work by Romare Bearden, a sort of coda to the exhibition, sounds a reminder of the struggles that brought us to this present moment, in which we can engage the complexities of Black art through shows like this one. Bearden, who came later, was not an artist of the Harlem Renaissance, though his work certainly stands on its foundations. Although the exhibition does not mention it, he is linked to this history in another way: In 1969, as a founding member of the Black Emergency Cultural Coalition, he was among the artists who called for an urgent protest of “Harlem on My Mind.”

Bearden’s work, like his activism, gives us a chance to reflect on the legacy of the Harlem Renaissance. In his massive and sprawling 1971 collage, The Block, we see Harlem and its residents through the open windows of apartment buildings, where tiny and intimate scenes in photo collage each becomes a work of art on its own. These city blocks, which imparted an ethos to the world, are not knowable from a single view. You need to get up close, to get into the thick and the mix of it, to understand and appreciate this Harlem. We could say the same about the Met’s exhibition, where each work opens a new window onto the Harlem Renaissance.

Rachel Hunter Himes is a writer, museum worker, and a PhD student in the Department of Art History and Archaeology at Columbia University.

Source: The Nation

Featured image: Aaron Douglas, from Aspects of Negro Life: From Slavery to Reconstruction, 1934.