A new Urban Institute report shows that capital in Baltimore flows along the city’s historic racial redlining patterns. David Goldman/AP

The solutions to Baltimore’s inequitable financing problems must be as radical as the policies that segregated the city in the first place, says Lawrence Brown.

On December 19, 1910, the city of Baltimore passed an ordinance that a New York Times writer called “the most remarkable … ever entered upon the records of town or city of this country.”

The ordinance made it illegal for any black person to live in a white neighborhood, and vice-versa, codifying the existing racially segregated residential patterns in the city into law. Although the ordinance was eventually dismantled, it had already enshrined racial neighborhood compositions such that when the Federal Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC) drew up maps for where banks could or couldn’t make loans, it easily zoned black neighborhoods into the couldn’t column—what we know today as redlining.

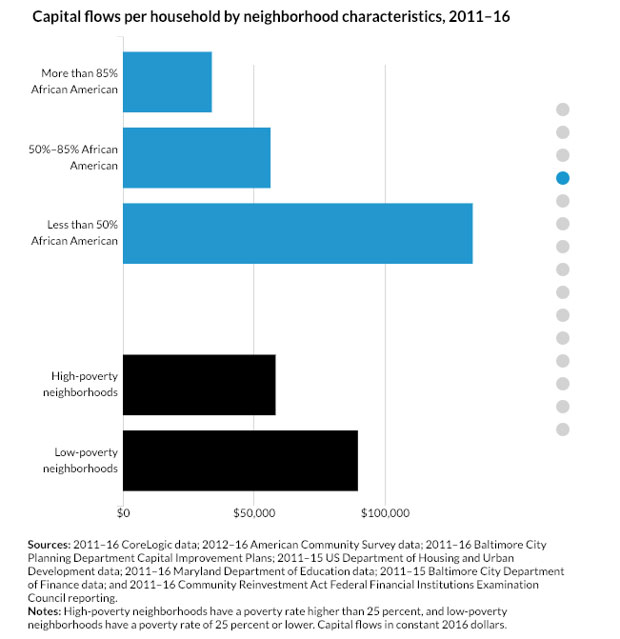

A century later, race still determines where private lending and investment happens in Baltimore, despite the outlawing of redlining. According to a new report and mapping tool from the Urban Institute, neighborhoods that are predominantly white received four times the capital investment of neighborhoods where the black population was more than 85 percent between 2011 and 2016.

Urban Institute

This is why reparations for the city’s black neighborhoods are in order, says Baltimore’s Lawrence Brown, a professor at Morgan State University who made The Root’s annual list of most influential African Americans last year.

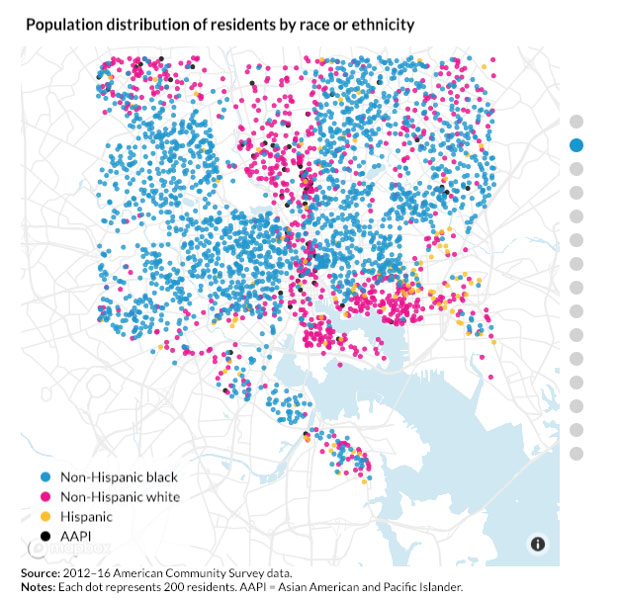

The Urban Institute report, “’The Black Butterfly’: Racial Segregation and Investment Patterns in Baltimore,” takes its title from Brown’s 2016 observation of a butterfly-shaped spatial layout of Baltimore’s black neighborhoods and “L”-shaped pattern for white neighborhoods. The term has since inspired several visual strategiesfor mapping where opportunity has and hasn’t been presented in the city. Brown gleaned these patterns from the racial dot maps created by Dustin Cable for the University of Virginia Weldon Cooper Center for Public Service in 2013.

Given that segregation in both living and lending has persisted for so long in Baltimore, Brown is proposing a dual-edged reparations package: one that would allot $290 million annually to the most severely redlined communities over the next few decades, and a $3 billion racial-equity social impact bond.

This proposition is far more generous than any other investment program for marginalized neighborhoods in play, in Baltimore or anywhere else—a Black Butterfly New Deal of sorts—but Brown says it is what’s required for so many decades of neglect.

“The New York Times article says in 1910 when the first racial segregation law was put into place in Baltimore that it was ‘radical’ and ‘far-reaching’,” said Brown. “So I say, OK, well if the imposition of racial segregation is radical, then the solutions have to be radical as well.”

Urban Institute

Indeed, the Times called Baltimore’s 1910 ordinance “the most pronounced ‘Jim Crow’ measure on record,” largely because it reached farther than any other Jim Crow policy in the South in terms of living arrangements. But that’s because most cities in the South didn’t need a legal proscription of racially integrated living.

“In the Far South the negroes would never dream of pushing their way into the white residential districts and intruding themselves upon the dwellers there,” Baltimore’s mayor J. Barry Mahool told The New York Times in 1910. “What the result of such action would be, if such were taken, I presume the readers of The Times are about as well able to guess as I am, if they have kept up with current events in the South.”

The events he was referring to were a maelstrom of lynchings of African Americans who dared cross color lines, or their houses being bombed, a visit from the Ku Klux Klan or, at best, a cross burned on their front lawns. The 1910 ordinance was hence sold as a solution to the inevitable violence that would come should black and white families live too closely to one another.

In 1910, African Americans were flooding cities like Baltimore as part of the first wave of the “Great Migration”—or, as the Equal Justice Initiative calls it, “massive forced exodus“—and Baltimoreans were shook. Not only did they believe that violence would follow black people into their neighborhoods, but that their property values would drop as well.

The U.S. Supreme Court ruled in 1917 that the residential segregation ordinance was unconstitutional, but what these shook white families couldn’t accomplish through law they obtained through finance. Homeowners associations and real-estate lobbies came up with lending protocols that would ensure that black families would stay in their own neighborhoods, and that little to no investment would follow them. The 1977 Community Reinvestment Act was supposed to halt and reverse the redlining damage, but it only persisted and evolved.

The Urban Institute’s “Black Butterfly” mapping tool recounts where and how economic inequities continue to be distributed across Baltimore today. CityLab asked Brown to explain some of the maps from the application and why his reparations proposal might be the city’s best hope for helping Baltimore’s most financially distressed black communities.

CityLab: How has the Community Reinvestment Act failed Baltimore?

Lawrence Brown: It was never enforced in any real powerful way. It was designed to undo redlining—to ensure that banks that formerly did not even have branches in black neighborhoods, and that weren’t lending in black neighborhoods, and weren’t offering capital for homes and for small businesses in black neighborhoods, would start doing so. But in fact I would argue that redlining has gotten worse. Since Freddie Gray’s death, two Bank of America branches have closed near his neighborhood—the one at Mondawmin Mall and the one further up in West Baltimore in the Reisterstown Road Plaza. So what we’re seeing is these bank deserts in redlined black neighborhoods.

When Freddie Gray was killed by police, there were stories about how millions of dollars had previously been infused in his Sandtown-Winchester neighborhood. And yet it was still struggling. How does that fit into the redlining narrative?

The city and other private parties and philanthropy embarked on a maybe $130 million redevelopment effort back in the late 1980s and ‘90s. But what we’re seeing with the Sagamore Development company [Editor’s note: This company is redeveloping the industrial waterfront Port Covington neighborhood with a new Under Armour headquarters as its anchor] currently is that to build that community, it needed at least $535 million in funding from the city. My question is, if we’re saying that it takes $535 million to build up one neighborhood, what made us think that $130 million was enough to rebuild Freddie Gray’s neighborhood? The answer is apparent. It wasn’t enough.

The promise of Trump’s Opportunity Zones is that it will spur investment in economically starved communities. Are you optimistic?

What you can see from federal urban policy overall—whether you’re talking about Model Cities, or Enterprise Zones under [former President Bill] Clinton, Promise Zones under [former President Barack] Obama and now Opportunity Zones under Trump—you can see that historically none of these programs have worked. The reason why is because these cities are still very much segregated, and in Baltimore’s case, hyper-segregated. So capital has a way of flowing into the areas that are already doing well and not so much into the areas that are not.

If you look at the Baltimore Development Corporation page where they list the communities where Opportunity Zones can be located or can receive funding, you see downtown on that list; you see Port Covington on that list. You see communities that have no business receiving extra capital on that list. And this is true nationwide. The Brookings Institution talks about the dangers of this, how Opportunity Zones could fuel gentrification if investors are just going to pick areas where there’s already funding being poured in, or where they see an influx of capital already taking place.

I think that’s what’s going to be true for Baltimore as well. This idea that Opportunity Zones are going to be a panacea—that’s not gonna happen. Not in a hyper-segregated city where redlining is still going on.

The Urban Institute report notes that public sector investments have actually been flowing to Baltimore’s poorest neighborhoods, but mostly from federal programs such as CDBG and HOME fund programs. Meanwhile, the city’s own capital improvement financing has flowed more to mixed-race neighborhoods and predominantly white neighborhoods than those with upwards of 85 percent black populations. Is the city missing the mark?

You see these stories in the newspaper where Baltimore City public schools don’t have heat in the winter and don’t have air conditioning in the summer. Somebody posted a video where the city schools have had leaks in the ceiling and moldy pipes. The dollars to fix that come from the capital budget, but we’ve had almost 80 public schools closed since the ‘80s. A lot of those school closures are disproportionately in black neighborhoods. The condition of streets and a lot of our infrastructure comes from that capital budget. The fact that the city is spending more in predominantly white neighborhoods compared to black neighborhoods, to me, is particularly appalling.

This is one reason permanently closing public schools due to low test scores is wrong.

Black public schools receive poor funding, so Black children are exposed to heat/cold, rats, water, lead, mold, etc.

These conditions contribute to low test scores! https://t.co/awR1gatbLC

— ??♂️??♂️???? (@BmoreDoc) February 7, 2019

The city’s Neighborhood Impact Investment Fund is $55 million. I think those type of funds are actually a response to the data showing inequities, but on the other hand, they’re pennies on the dollar compared to the $535 million the city is giving to Sagamore Development to develop Port Covington. That one community is receiving $535 million in funds whereas you’re telling me for the entire city $55 million is going to somehow make a real dent in the issues that we have? I reject the notion that it is even framed as an attempt to address racial equity. The number is too small.

So what is Baltimore’s moonshot solution here?

One, there should be Baltimore neighborhood reparations. We should take 10 percent of our budget, which right now is $2.9 billion. That’d be $290 million, to be split up proportionately where there has been severe redlining put in place for decades.

I imagine at least 30 to 40 years, if not more, of Baltimore neighborhood reparations in places administered through democratically elected community councils. They will decide where the funding needs to go, because the people who are living in a community best know its needs. And then there’s what I call a $3 billion racial-equity social impact bond, where about half of that should go towards getting lead poisoning out of the environment, but then the other half is a combination of addressing housing, violence, substance abuse, and other critical issues that we have in our city.

The Baltimore reparations package would function as actually changing our city budget, because right now, we spend more on city police than we do on health, housing, arts, parks, community development, workforce development, and civil rights combined. That’s changing from an apartheid budget to a freedom budget. And I use the language “freedom budget” because that’s what Dr. King and the SCLC were promoting on the national level back in the 1960s. I think it should be applied for local governments as well.

Brentin Mock is a staff writer at CityLab. He was previously the justice editor at Grist.