Descendants of the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre are seeing their story being told, but have yet to receive reparations.

Documentaries and news reports marking the centennial of the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre are scheduled to air across TV this weekend and into June, including on History Channel, PBS, CBS, CNN, OWN and National Geographic. All of them are worthwhile viewing. Regardless of which you watch, it is crucial to know that the destruction of Tulsa’s Greenwood district is not a one-off tale from 100 years ago.

For the Black community still living there, it is an ongoing concern.

“The critical piece here is covering this story from the perspective that the job is not done yet,” stressed community activist Greg Robinson II, a descendant of survivors appearing in both PBS’s “Tulsa: The Fire and the Forgotten” and History Channel’s “Tulsa Burning: The 1921 Race Massacre.”

“This isn’t a story that has an ending because justice hasn’t been done,” Robinson adds. “The massacre should be covered in a way where the reality is that it’s been a massacre since 1921. And I think that if that’s the case, Tulsa will be able to be seen in in a light that is really a microcosm of what has happened to Black people across this country.”

Oklahoma’s Republican-controlled state legislature knows this. It is aware of all the ways the state has failed to act since the very same government body authorized a commission in 1997 to research the overnight obliteration of Greenwood in 1921, when it was the wealthiest Black community in the country.

Based on that commission’s findings, five specific recommendations were made in 2000. They include direct payment to survivors and descendants of the survivors of the Tulsa Race Massacre; a scholarship fund for students affected by the massacre; the establishment of an economic development enterprise zone in the historic area of the Greenwood District; and a memorial for the reburial of any human remains found in the search for unmarked graves.

Oklahoma hasn’t followed through on any of these.

Members of the state’s legislature surely witnessed at least some of the testimony the last three living eyewitnesses to this horror – Viola Ford Fletcher, 107; Lessie Benningfield Randle, 106; and Hughes Van Ellis, 100 – recently provided before the House Judiciary subcommittee in Washington, D.C., which is also considering reparations for Greenwood survivors and descendants.

Instead of seeking to meaningfully grapple with this stain on its history, Oklahoma’s state legislature passed a new law banning Oklahoma teachers and school administrators from requiring or making part of a course several concepts about race and gender.

This includes any lessons that may imply “an individual, by virtue of his or her race or sex, bears responsibility for actions committed in the past by other members of the same race or sex.” Oklahoma Gov. Kevin Stitt signed this into law while holding a seat on the Tulsa massacre’s centennial commission, a position his office later explained away as “purely ceremonial” when the commission removed him.

Thus, one can understand the viewpoint of Oklahoma State Rep. Regina Goodwin, who lends her perspective to “The Fire and the Forgotten.” Goodwin, a descendant of the massacre’s survivors, appreciates renewed attention and media coverage devoted to the centennial. Goodwin also stresses that she doesn’t see very much changing as a result of it. After all, the national media showed up in 2000 too.

“I hope folks are clear about that,” Goodwin told Salon. “We can talk about all of the activities. We can talk about all of the folks remembering. But again, when it comes to something substantial that has come out of it for those descendants and survivors, there is no difference.”

Yet. Hopefully.

Nevertheless, Goodwin views the latest efforts to expose Greenwood’s history as a positive development. “Anytime you can tell the story and tell it truthfully, people become more educated. People become more aware. It’s a conversation that needs to be had because we’re never going to forget.”

PBS’ “Tulsa: The Fire and the Forgotten” and History Channel’s “Tulsa Burning: The 1921 Race Massacre,” join the CNN debut of “Dreamland: The Burning of Black Wall Street,” and the one-hour CBS news special “Tulsa 1921: An American Tragedy,” in addition to other coverage running throughout the weekend.

The wholesale wreckage of the Greenwood community is believed to be the single worst incident of racial violence in American history. It occurred shortly after 1919’s Red Summer, when white people committed acts of deadly violence against Black people in dozens of American cities.

But the decimation of the place known as Black Wall Street is especially significant owing to Greenwood’s financial stature. By 1921 its Black families had built substantial wealth. The district was home to many successful businesses, a thriving network of professionals and a self-sustaining local economy, including the largest black-owned and operated hotel in America. All of this was created by Black people a generation removed from enslavement.

That all ended with a pogrom that began on May 31 and ceased, officially, on June 1, leaving an estimated 300 people dead, and destroying 35 square blocks, 1,256 homes and 200 businesses. (At the time the state’s official death toll was 36.) White pilots employed aircraft to drop incendiary devices on their Black neighbors. Tulsa’s fire department allowed blazes set by white mobs to consume Greenwood. Local law enforcement deputized and armed white men, encouraging them to shoot Black people down in the street as they were trying to escape. One witness said he saw Tulsa police officers torching Black homes.

Around 10,000 Black Tulsans lost their homes and businesses in the massacre. Six thousand were forced into local internment camps, and eventually the National Guard forced them to clean up the ruination their white tormentors left behind.

None of the perpetrators has been charged despite the wealth of photographic evidence showing individuals participating in the atrocities. Heinous images of charred bodies and destroyed houses were in fact turned into postcards and sent to white supremacists in other states.

The fact that most Americans knew nothing about the massacre until it was portrayed in the HBO series “Watchmen” and “Lovecraft Country” indicates how effectively witnesses were terrified into silence. These new documentaries revisit the story from various angles, with History’s approaching the massacre and direct aftermath with forensic detail bolstered with accounts from historians, survivors and local residents.

“Tulsa Burning” director Stanley Nelson familiarized himself with the history of Black Wall Street while making 2019’s “Boss: The Black Experience in Business.” He knew the story of Greenwood merited more than the minutes-long segment devoted to it in that work, and began producing his two-hour film in 2020.

For him, the most amazing discovery was the wealth of film that recorded what life in Greenwood looked like before 1921. “Somebody in Greenwood had a movie camera and shot film in 1920,” he said. “So we see the people, sitting on their swings, on their porches, proud of what they’ve accomplished. We see the Black sheriff with his gun, we see people herding cattle, building churches.”

“We really wanted to have the viewer understand what was created in Greenwood,” he added. “You can’t feel the loss unless you feel what was there.”

“Tulsa: The Fire and the Forgotten” also explores Greenwood’s founding and rise, drawing extensively from DeNeen L. Brown’s coverage in The Washington Post. While it also explains what happened 100 years ago, but the ongoing effort to recover remains and the uphill battle to attain meaningful restorative justice receives detailed focus.

This part of the story takes on a renewed urgency given the age of the three remaining survivors. Robinson and Goodwin stress that the priority is for them to receive some compensation ensuring they and their families are well taken care of.

But financial reparations are only a start. A report referenced in The Harvard Gazette places the estimated value of Black property wiped out by white rioters at $200 million in today’s dollars. But the price tag of the community’s vanished wealth accumulation, possible business expansion and innovation, all stolen from it that day, are much higher. Tulsa’s Black community never recovered from the 1921 tragedy, and the wealth gap between its Black and white residents is substantial.

“This is exactly why when you talk about the national reparations debate, Tulsa is so important,” Robinson explained. “It’s such a tangible visual of what was taken and what was never returned. And so I think that there’s a real argument to be made that we’ve got to find justice, and Tulsa is prerequisite for finding justice across the country for Black folks.”

It must be said that other losses are profoundly irreplaceable: murdered family members whose remains were never found, potentially buried in mass graves authorities are still working to locate.

Survivor descendant Brenda Nails Alford, granddaughter of a “proud, college-educated” entrepreneur, sums up the travesty in “Tulsa Burning” by reminding viewers that Greenwood’s residents did everything Americans expect law-abiding, tax-paying citizens to do. “They wanted to be successful. These were proud, upstanding members of our community who simply wanted a piece of the American dream and truly received a nightmare.”

These films and specials, along with the documentaries that came before them and any coverage that comes afterwards, are at least doing their part in breaking what Goodwin defined as “a conspiracy of silence.”

For the representative and every Greenwood resident keeping the story alive when the cameras aren’t there, “we’re going to be forever pushing for progress and justice,” Goodwin said. “We owe that to our ancestors and to our current community. So we press on, and we know that it’s time, and it is past time. We wake up every day knowing that as long as we’ve got life, we can get it right.”

“Tulsa Burning: The 1921 Race Massacre” 8 p.m. Sunday, May 30, 2021 on The History Channel.

“Tulsa: The Fire and the Forgotten” 9 p.m. Monday, May 31, 2021 on PBS.

“DREAMLAND: The Burning of Black Wall Street” 9 p.m. Monday, May 31, 2021 on CNN.

“Tulsa 1921: An American Tragedy” 10 p.m. Monday, May 31, 2021 on CBS and will be available to stream on Paramount+.

“The Legacy of Black Wall Street” 9 p.m. Tuesday, June 1, 2021 on OWN, with its second hour airing at 9 p.m. Tuesday, June 8.

“Rise Again: Tulsa and the Red Summer” 9 p.m. Friday, June 18, 2021 on National Geographic. It streams on Hulu starting on Saturday, June 19.

Source: Salon

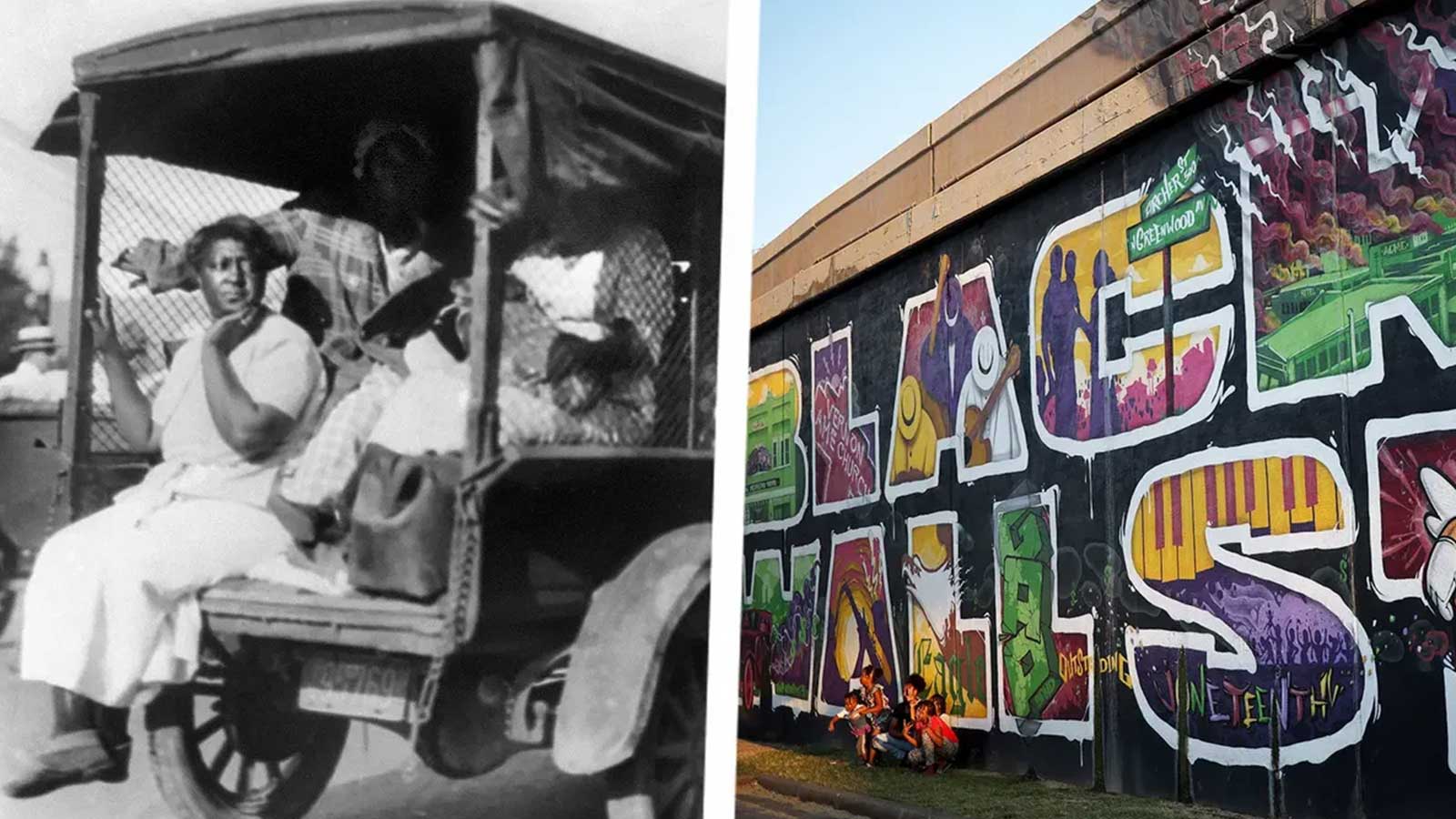

Featured Image: Woman rides in a truck loaded with people and possessions during the Tulsa massacre in 1921 | Mural marking Black Wall Street massacre in the Greenwood District (Photo illustration by Salon/Greenwood Cultural Center/Win McNamee/Getty Images)