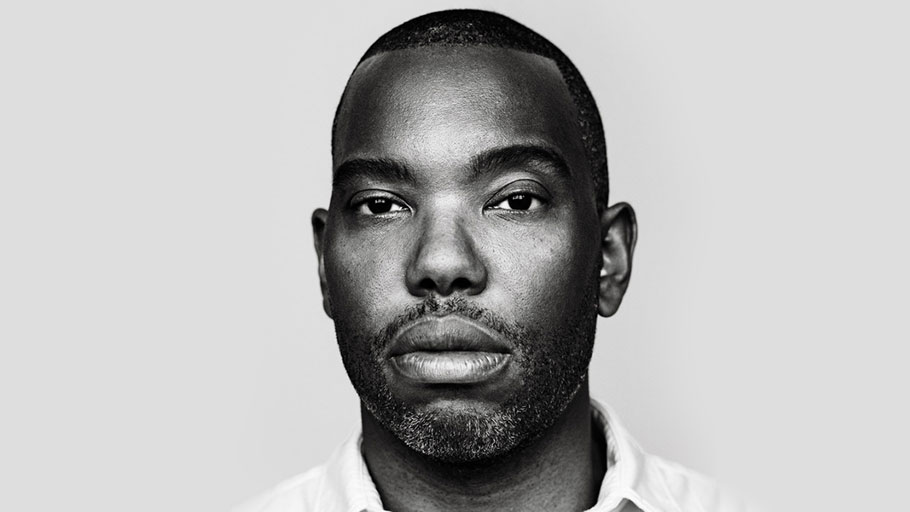

Ta-Nehisi Coates on What Changed in the ‘Obama Decade’ and What Didn’t. Talking reparations, Kaepernick, and the first black president with the writer who may be the definitive chronicler of racial politics in the 2010s.

By Zak Cheney-Rice, Intelligencer —

If the racial politics of the 2010s has a definitive chronicler, it is Ta-Nehisi Coates, whose magisterial 2014 Atlantic essay “The Case for Reparations” forced Americans to reckon with slavery, Jim Crow, and redlining in ways that many of them never had. Since the essay’s publication — which eventually prompted a congressional hearing on the subject this year, at which Coates testified — the 44-year-old has won a National Book Award for his 2015 book, Between the World and Me, and was awarded a MacArthur “genius” grant. More recently, he’s been writing fiction: He scripted a run of Marvel’s Black Panther comic and published his celebrated first novel, The Water Dancer, which concerns an enslaved man gifted with supernatural powers in antebellum Virginia. Coates’s expansive imagination and incisive, historically grounded writing about Barack Obama, Donald Trump, and cultural figures like Kanye West has cemented his status as a writer through whose eyes many Americans have come to understand the modern era — including me.

Let’s talk about race and politics in the 2010s.

It’s Obama’s the course of his presidency, Obama and Coates seemed to be engaged in a running debate about the pace of American progress on race. At times, the conversation was direct. decade, unquestionably, which is not to say he was always the prime actor, but I think the force of a black president was such a historic and seismic event that everything, including my conversation with you right now, just was touched by it. It’s really like if I had to pick a singular thing that defined the decade, it would probably be the thing that happened before the 2010s, and that was his election.

The actual start of the decade did mark the beginning of an ill-defined something in politics with the rise of the tea party. If you wanted to mark it there, you would say his losing the House majority, right?

Yeah. We get this electoral manifestation of right-wing backlash for the first time.

How did 2010 affect your understanding of political partisanship? Is partisanship a useful frame through which to understand racism in the past ten years?

I would probably say it the other way and say racism is a useful frame to understand partisanship since the 1960s. The Republican Party is effectively a white party in this country. It’s the party of a white majority that greatly fears becoming a white minority. You have to separate the fact of Obama being a black man from the fact that that black man represented a multiracial party. That’s very, very important. One of the things that I actually even heard Obama himself say was, “Well, I don’t know how much of the opposition is about race because Bill Clinton got it pretty bad before me.” But see, Bill Clinton represented the party that was most associated with black people. He represented, too, a multiracial party. I think Hillary Clinton would have been racialized in the same way. I don’t think you escaped it because you’re white. True, Obama was a much more intense representation of it, but it was really those two things working together. It’s the figure of a black president. At the same time, that figure representing a multiracial party in opposition to a party that is effectively a white party. As much as the tea-party movement in 2010 is just a line of demarcation, you have the current president’s invocation of birtherism, and birtherism is little more than telling the first black president, “Go back to Africa.” It’s not a mistake that throughout Obama’s presidency, you could poll the Republican Party and find anywhere from half to a solid majority of people who actually were birtherists. That’s not accidental. Racism is and was core to what the Republican Party is, which is not to say it has no manifestation and no effect in the Democratic Party.

Birtherism strikes me as one of the few things Trump has done that Republicans haven’t been explicitly willing to defend, even as they do stuff like rationalize his defense of white supremacists in Charlottesville. But there’s also been no broader reckoning with its effect or with how successful it was in getting a number of current Republican representatives into office, either.

Totally. Some of them know better, but that’s always been true. George Wallace — you know his story. Wallace was liked by the NAACP and was liked by black people, and his earliest campaign for governor did not want to make segregation and racism central to his campaign. Then he lost to a guy who went out and did that. He said, “I will never be out-n—–ed again.” He said, “I tried to talk about good roads and good schools and all these things that have been part of my career, and nobody listened. And then I began talking about ‘n—–s,’ and they stomped the floor.” It’s a guy that probably knew better. Some of these folks, if they are not racist themselves — and I’m willing to grant that — they don’t find racism so odious and so offensive that they either (a) would not stoop to using it themselves or (b) don’t mind the occupant of the White House using it or being a racist himself.

It does seem odd that with Charlottesville, they’ll bend over backward to be like, “Oh, he didn’t mean that when he was talking about very fine people on both sides,” but with birtherism, Jared Kushner’s like, “I wasn’t around for that. I don’t know about that.” It’s just a very kind of confusing divide to me.

Whenever you have power, you get to delineate history where you want to delineate history. It starts where you want it to matter.

You’ve said that Obama’s presidency made your work possible in that it created this interest and audience for the type of analysis that you were uniquely well positioned to provide. If that’s the case, why do you think people gravitated toward your fairly downbeat analysis of Obama, this figure who inspired a lot of hope and warm feelings?

I really don’t know. I’ve always thought of my job as to try to arrive to some sort of truth, render that truth in a way that is as convincing and as powerful as possible to myself, and then present it to the world. But why people are moved by the things they are moved by, I don’t know. I will say this: I think I am one who has always been attracted to the power of storytelling, whereas if I were, say, a columnist at the New York Times, I don’t know that that effect would’ve held in the same way.

Do you think what Obama made possible in cultural conversation and political conversation extends to this resurgent interest in black cultural products? I’m thinking of stuff like Black Panther, Barry Jenkins’s work.

I really do, because I think there are two ways of analyzing Obama. There’s a politics of him, and there’s Obama as a mythical figure, the symbolic aspect of what he is. People sometimes think the symbols are not very important. I think symbols are really, really important. There’s a reason people fight over the Confederate flag. There’s a reason that Charlottesville starts with wanting a statue of Robert E. Lee to remain. Symbols open people’s minds to what’s possible. It actually was quietly really important that while Barack Obama never disguised the fact that he was biracial, he identified as a black man. He was really clear about that. He managed to assert himself as a black person without any sort of denialism about what his actual ancestry was. I think that was really inspiring to a lot of black people and a lot of white people. I don’t think it was everything. I don’t think it was enough, but I think one should not underestimate the power of Obama as a symbol of the first black president.

Because I’ll tell you one thing, if Obama, let’s say, had been Bill Clinton, right? Like if Obama had been credited to all these rumors of him womanizing or fraternizing with all these white women, and if he had been found to have, God forbid, actual rape allegations on top of that, and if he had been found to, I don’t know, carry on an affair with some 22-year-old white intern, the effect would have been devastating. Negroes would have been hanging their heads like, I cannot believe. And that’s about the symbolism. That’s not about policy.

Is it that Obama was a symbol we could collectively feel good about, who made us feel good about ourselves and our place in America as black people, while also making white people feel good about their ability to tolerate us?

Yeah, it probably did. People forget that Obama is immensely popular with black people, like probably the most popular person maybe after his wife. Why is that? Is that because of policy? No, he is confirming something in them. There’s something in black folks that they feel good about when they see him. And there probably is a critical mass of white people who feel good maybe for other reasons but feel good themselves. Part of that is about the way he conducts himself in public. When Michelle said for the first time in her life, she’s proud to be an American, I bet a lot of black people felt the same way. You got this guy, the embodiment of all of these middle-class values that America preaches and also the black community actually believe in themselves, and here it’s embodied and modeled before the world for eight years. Before Obama, most famous black people were all entertainers. And now you got an actual head of state who conducts himself in a way that you would want your son to conduct himself.

Has that then translated into, okay, so maybe there’s more to us as black people that’s worth investing in, and that’s why we have these cultural products?

Probably not for most, but for some critical mass of white people who probably were already somewhat susceptible to it, yes.

What to you are sort of the most important, impactful, memorable, cultural products of this decade?

Jesmyn Ward, Salvage the Bones, which I just finished a couple of weeks ago and I’m still recovering from. Kendrick Lamar —

Any particular album?

I got to say Good Kid, M.A.A.D City. I felt like he was talking about my childhood, 20 years before. I think about “The Art of Peer Pressure,” and that just sounded like being a kid in the late ’80s, early ’90s. Creed is incredible. Absolutely marvelous film. What it does that it probably doesn’t get enough credit for is it takes a white myth that was, let’s just say, problematic, and it heals. It heals the disturbing things about it, actually. You know what I mean? The Warmth of Other Suns, is that in the period?

That was 2010.

So The Warmth of Other Suns. Absolutely revolutionary. I always felt like it was the spiritual mother of “The Case for Reparations.” What it did was focus on that class of strivers, as opposed to how most books about black people focus on the black poor. It pointed out to me that people think of racism as synonymous to class. What Isabel was showing was even among people who you think of as middle class, they actually have not escaped. You know that you’re not talking about another manifestation of class. You’re talking about an axis that works independent of class along with class. That race is itself a kind of class. And no matter how a much of a striver you are or how middle class you are, it still exerts a penalty on you.

I think of the late ’80s and early ’90s as this kind of explosion of black popular culture with Spike’s heyday and all these black sitcoms that kind of fizzled. Does this current wave feel sustainable in a way that that wasn’t?

I think this time is fundamentally different. The technology has changed.

You talking about the ’80s, you’re talking about no internet, right? The pathways to really get a message out are constricted and the people that control those pathways don’t tend to be black. Also you’re talking about a point that is closer to the civil-rights movement. It is much, much closer to the point where at least nominally America has embraced integration. When I think about somebody like Jesmyn Ward winning the National Book Award twice, right? When I think about Barry winning the Oscar, when I think about Ryan and Creed and how Creed should have won the Oscar. And then when I think about Black Panther and it’s the first comic-book movie in the Best Picture conversations. When I think about how Ava basically got Linda Fairstein shunned by society, I think that’s a different level of power. Obama’s been gone for, what, three years now? Black Panther is after Obama, When They See Us is after Obama. And I know I frighten people even in saying what I’m saying here, but I think probably what you have is more black people in institutional places. You probably have, again, that small but critical mass of white people who’ve been influenced. Black people have shown that you can make money off of black things, as crass as that sounds. We got to talk about Kaepernick, too. We don’t have to talk about him right now, but we got to talk about him before we —

Now’s a good time. I’m embarrassed to say I have not been following the tryout drama as closely as I should have been.

I don’t think you missed much.

Well, talk about it. What’s on your mind about Kaepernick?

I don’t know how things will be looked at 20, 30 years from now, but I think Kaepernick is really, really important.

Is he like Muhammad Ali important in that, like, in 50 years everyone will pretend that this was our hero all along?

I think when he’s no longer dangerous, when he’s no longer trying to get a job, when he’s 40, when he’s 50, a lot of people will be standing up to honor him. This is like how when everybody looks back at the civil-rights movement, they think everybody was like, “Yeah, that’s a great idea.” Clearly, we recognize Bull Connor as the enemy, and this is the good guy. That’s not really how it goes, man. This is exactly like it’s happening with Kaepernick right now. It’s a little messy, you know what I mean? The people pushing for the change ain’t always right. They’re not always pursuing it in the best strategic fashion. The whole country is divided and polarized; the black community itself, polarized and divided. But once the dust settles, I think it will be quite clear what happened.

Even just watching how the public workout went this weekend, I’ve marveled at how well the NFL has normalized the blackballing of Colin Kaepernick. A lot of people basically tried to answer the question, did Kaepernick conduct himself appropriately this weekend? And so the lines of debate begin right now; they don’t begin with a multibillion-dollar business that has an effective monopoly depriving somebody of the right to work because they don’t like what they said, while at the same time granting that right to work to people who have all sorts of problems and issues. Here we are, debating whether Colin Kaepernick should have worn a Kunta Kinte shirt. Meanwhile, Richie Incognito is fine. It’s a real lesson that, despite whatever progress, when you have power, you can do horrible, inhumane, deeply wrong things, and you can normalize those things.

In many ways, this Kaepernick thing is a perfect emblem of white supremacy because they call you the day of the tryout and tell you you got two hours to decide, but it’s either this way or no way. But we never take a second to analyze why are we fighting on this ground? How did we get to the point where the person who’s actually doing the blackballing is considered an equal and legitimate partner? I think that mirrored a larger frame for the politics that happened in this era with Obama and everything around race. People who had done horrible and heinous things nonetheless conferred a kind of legitimacy.

But at the same time, Kaepernick got the 30th-anniversary “Just Do It” Nike campaign. He’s being lionized in this other sphere, which is also a related sphere. NFL and Nike, they do business, right?

They’re unrelated in terms of who they think their base is. Nike, at least part of its legitimacy, it feels, comes from the streets, and who it sells to is young people. But I take your point. It’s very different than Muhammad Ali, right? There was no place for Muhammad Ali to go to in that same sort of way. And I think part of that is the real progress that has happened in terms of how black people are seen in the wider society. Even young people, you probably couldn’t have put Muhammad Ali in an ad in 1968 or done what was done with Colin Kaepernick. He’s eating just fine in a way that Muhammad Ali was not.

Can we talk about Obama’s post-presidency? What do you make of it?

I don’t know. I think in the midst of everything that has happened, I understand the president saying, “Listen, I’m not going to comment on the doings of my successor.” That’s the tradition, right? But I think it puts in stark relief some of the other things Obama is willing to comment on. It’s a little tough to hear, in the midst of the administration pursuing a policy that literally puts children in cages, the president bragging about sexual assault, believes in insulting somebody in real time while they testify before Congress, claiming during his campaign that somebody can’t be his judge because, in his word, he’s a Mexican — it’s tough to see somebody that has the gravitas of Obama, then at the moment they’re speaking out, it’s about some kids on Twitter and cancel culture. That’s a little hard to take. Young people have no power. Obama can’t be canceled, not by them, but the people that are actively at this very moment trying to cancel him, the person who designed his entire presidency around the cancel culture of the Obama administration itself —

By that you mean negating the legacy, negating the gains, negating the policy?

Totally. Trump has been really open about this. His entire identity is a negative identity, by which I mean he defines himself by his ability to take apart the legacy of Barack Obama. It’s just not clear to me what the advantage is in Obama deploying his power in that way. I don’t know who it helps.

If Joe Biden was black, even black people would be like, ’Oh, absolutely not.’

It’s understandable to me that a president would consider it politically expedient to avoid talking about racism in any kind of profound, challenging way, which I think is the core of your criticism of Obama, that he really avoided this subject.

But more than that, the way he addressed people without power. There’s probably a strong political argument for not saying white supremacy is at the core of America. Listen, you’re a president of the United States. I get it. I’m not saying you have to talk like me, but I just think the harshness in the way he talks about people who lack power. I guess what he would say is, “I’m trying to tell them something that would actually help. Da da da da da.” I don’t know that it always comes across that way. I think as a whole, our obsession with young people and what’s happening on college campuses is deeply unhealthy. It bespeaks people who don’t remember being young themselves. So maybe he’s just a part of that, but when the damage is done by Trump and they ask, “What was the first black president talking about?,” and the answer is some kids on college campuses or some people on Twitter. Well, I just, I don’t like how that sounds.

There are now three black candidates running for the Democratic nomination, none of whom seem to be catching on with voters in any meaningful way. What do you think a black candidate has to do to get elected post-Obama?

First of all, you can’t be the first again. That’ll never happen. So the sheer amount of energy that was generated at that particular moment in time following a president who had just basically run the country into the gutter, failed wars. Two failed wars, economy on the brink, all of everything feeling like it’s breaking. Then you get this black dude who comes in, and he’s able to not just capture that feeling from larger Americans, but very specifically become the embodiment of certain things about the black imagination or the black political imagination. You’re just not going to do that again. So that’s the first thing. The second thing is that Barack Obama was not the first black dude to run. There’s this sort of notion that, oh, Barack Obama shows up and then black people just sort of fall over themselves to vote for him. Black people are actually very savvy and very canny. I don’t support Joe Biden for president, but I totally understand why most black people do. I totally understand why the person that’s running second to him in a lot of places is Bernie Sanders. It’s not a mistake. The other thing too is people forget that Obama was just a damn good politician. No disrespect, but what we got? Three candidates? Do any of them have the oratorical skills that Barack had?

Absolutely not.

If he was white, he would have been a remarkable figure as a politician.

The notion that you’re just going to show up and be black and we’re going to follow — it just don’t work like that. The larger populace is sort of amazed that Kamala Harris or Cory Booker hasn’t captured more of the black imagination and black folks in polls, but it’s not that amazing. Barack Obama is just a unique dude, man.

It does seem like the calculus post-Obama among black voters is who we think can win, and part of that calculus is white folks are racist. So what needs have to be fulfilled by a black candidate to win?

I’m not sure. Perhaps what would help is to understand who it could not be. No black person could be who Pete Buttigieg is. You’re not going to be mayor or whatever. You can’t be a black person who’s only been in there and then say, “Hey, I’m going to run the entire country.” That just don’t fly, you know? So it’s probably going to be somebody out of the Senate or the governorship somewhere. I don’t know what would have happened if Deval Patrick had a run from the beginning. I think you got to be a damn fine politician. And you can’t even be Joe Biden, by the way. I don’t even want to pick on Pete Buttigieg. If Joe Biden was black, even black people would be like, “Oh, absolutely not.” He’s going to get killed out there. Bumbling his way through shit. You’re like absolutely no, no, no, no. Absolutely not. But I think a lot of black folks are banking on the white candidate, which may not be wrong.

Trump did this big event in Atlanta recently where he’s promising to fight for every black vote, which was rightly ridiculed. At the same time, he did better with black voters than Mitt Romney or John McCain.

That’s a bad comparison, though. I mean, come on.

Well, let me give you a few other things. House Democrats did worse with black voters in 2018 than they did in 2016. Stacey Abrams in 2018 did worse in Georgia with black voters than Hillary Clinton did in 2016.

I still don’t buy it, Zak. You’re still not going to get me. But go ahead.

They’re obviously very small shifts. Who knows if they mean anything? They do suggest to me that —

They also aren’t apples to apples or oranges to oranges. Hillary Clinton is not running for the same office as Stacey Abrams was.

It’s not crazy to think that Trump showing up in Atlanta and at least trying, like, this dude has nowhere to go but up. The needle could be moved a point or two conceivably.

You know what I would like to see? I would like to see the past 20 years of voting data in terms of black people and Republicans. If you could show me a trend line that was only briefly interrupted by Barack Obama, then I believe you. But I think I’ve seen this comparison out there, and for the most part, you’re talking about different kinds of elections. The question to me is not “Is Trump more successful than Romney or McCain?” The question to me is probably, “Is he more successful than Bush?”

I don’t think he was.

That’s the closest like-to-like I can get. I think black support for Trump is vastly overstated I guess I kind of resent the basis on which the question is asked. Trump gets — how many more did he get than Romney and McCain?

It was a couple of points.

Meanwhile, white people are voting for a dude who bragged openly about sexual assaults. Why are we not afforded a couple points? Why can’t a couple n—–s be crazy? Excuse my language.

This isn’t to me a question of whether there’s something wrong with us, actually. My question is whether there’s something about Trump that is slightly more appealing, even to kind of fringe black voters.

What I am countering is the very fact that this is significant enough for us to talk about, I think, attests to the kind of, again, normalization that you get when you have power. There are much more significant factors than those two or three points in why Trump is in office. Why does he have power in the first place? I would argue that those two or three points are nowhere near as important as the fact that Trump basically got a majority of every single white demographic you could think of. Majority of every economic cross-section of white people. We’re having this debate about two or three points among black people. But it’s normal for white people to support the dude that thinks foreign policies should be done by tweet. Nobody goes to white people and says, “What in the hell is wrong with y’all?”

I think there has been a thorough critique of the white vote for Trump. Maybe especially in the circles that we are —

Probably so. In our circles, yes. I would agree.

You’ve withdrawn from both social media and nonfiction writing generally for a while to focus on stuff for Marvel and then The Water Dancer. Is there anything at all you’ve seen happen and been like, Oh man, if I wasn’t so busy doing this other stuff, that would be something I would really love to tackle in a big way?

All the time. I wish I was writing about Kaepernick right now. One of the decisions I had to make, though, was am I at my strongest commenting on the day-to-day, or am I at my strongest when I wait, hold my fire, watch, think, let things marinate, and then turn out something that’s more fully formed? This was part of leaving Twitter. I mean, one of the hardest things to do was I had to part with another portion of myself, the blogging portion of myself, the Twitter portion of myself, which I really liked. But the world kind of changed for me, and it became one in which I had to be a lot more careful about what I said and what I did and that’s okay.

Can you talk about your decision to leave Twitter?

You know, what happened was I realized that people were, like, eating off of me. I’ve got a buddy in another field who did something really popular, and he would get criticism sometimes, and he says, “It’s all right man. Everybody eats. I get to eat, the haters get to eat.” That was his thing. I didn’t realize people were eating, man. So every time I would write a piece, I’d get me like 50 fucking responses.

Like written essays, you’re saying?

There’d be like 50 op-eds to what I wrote. I was like, Damn, people are really eating off of this. And then it would be a click economy on Twitter. During the 2016 campaign, there was a dude and he would like record YouTube videos responding to what I wrote. I realized I have gone to a point where I have more influence and fame then I have thought to dream of. So when I say something, it’s no longer just the writing talking. So that changes, man. You start taking up oxygen in the room. Why don’t I cede some space. Why don’t I be a lot more discerning about when I talk, because what I really care about is the writing. I’m a happier person, by the way, too, having done that.

But I wonder if, do you feel any responsibility to the people? I think it’s fair to say a lot of people turn to you to help them make sense of this cultural moment in a way that was positive, people who made sense of the world through the lens of your analysis. Do you feel any kind of residual responsibility toward those people?

Are you talking about yourself?

I really miss you, man. Come back.

You can text me anytime!

But seriously, just one example: Conversations about racism are easier with a lot of white people I know. I can attribute that largely to your work.

I mean, that’s a good thing. I’m at the end of the book tour right now. I did a big thing in L.A. with Ryan Coogler where we talked to a church full of black folks. I did these small groups in Atlanta, in L.A., in New Orleans, where I got to talk to small groups of black folks. In the middle of this tour, I got to hang out on the Yard at Howard homecoming. I have no problem talking to my people. Something else happens with the larger and white public. That’s cool, too. I think there are very, very few writers who can say they don’t want a larger audience. And if I happen to get a larger audience but I can still stay true to those impulses and instincts that got me here in the first place, then I’m happy. I’m doing all right.

Your article “The Case for Reparations” is credited with reparations being discussed as a very serious policy proposal now. You testified in front of Congress about it. What have your one-on-one conversations about reparations with elected officials been like?

I’ve actually only talked to two people, Barack Obama and Elizabeth Warren. It was before she was a presidential candidate. I mean, maybe she was thinking about it. I didn’t get the impression she was. She had just read the piece and, I think, just thought it’d be really cool to talk to the person that wrote it. In terms of other candidates, I like the fact that I don’t really want to be the kind of person that’s consulted by candidates.

So when you were called to testify in front of Congress, nobody sat down with you? They were just like, “Come talk,” basically?

Yeah, that was basically it. I didn’t want to do it. I feel like I speak through the literature. At that point, I felt like I was stepping more into an activist role, and it’s not a space I really want to be in. But at the same time, I felt like so many black folks in the past have sacrificed for me to even have the privilege of saying I didn’t want to be in that role that I kind of had to.

Can you envision a scenario where reparations is (a) formally studied, (b) agreed upon as a thing that should be done, (c) paid out, and (d) ends up actually being enough to remedy the harms that that’s meant to address?

The first thing I would say is the scenario that you just outlined I would argue is not reparations. That’s a bribe. This is why it’s so crucial that it not just be a question of the money but it actually be a question of some sort of attempt to alter how we remember the past. If that goal were accomplished, you would not have a critical mass of Americans and white Americans wanting to wash their hands of it. They would see it as part of who they were and part of their responsibility. The notion, for instance, of reparations being paid out presumes something that happens over a one-year period or something and everybody walks away. I don’t think that’s what you’ll most likely see. First of all, you would most likely see a very decentralized process. I think the responsibility for instance, of elite universities would be very different than responsibility for the deprivations that the GI Bill did or the responsibilities of certain towns where black folks were basically forced to evacuate and leave under threat of being killed. You would see a suite of policies as opposed to a single unitary policy. In fact, this is actually what happened with reparations coming out of the Holocaust. There was no single, solitary act of reparation. There were several, actually, that are ongoing to this day, by the way. I mean, think about that. The end of WWII was 1945. Almost 75 years ago, man. Reparations are still being paid out for the detaining of Japanese-American citizens in this country. Well, the period of redlining is more recent than that. My hope would be there would be a profound reimagining not just of the African-American past and what was done to African-Americans in America and thus the American past in itself, but our responsibilities and how we deal with people in general.

Some of the criticism your work has faced on the left is that you overstate racism’s intrinsic nature in a way that casts it as this elemental force that will be with us forever. It’s baked into the soil we walk on, the air we breathe. Is this a fair assessment of your belief?

No, it’s not a fair assessment, and in defense of leftist critics, I love you, Zak, but I don’t even know if that’s a fair rendition of their criticism.

Do you not? Maybe I’m reading the wrong people.

No, you’ve probably read more than I have. So maybe it is. No, I think it’s totally wrong.

I do think that it’s easily taken away from your work that you believe, at the very least, that the work that needs to be done to end white supremacy in America is an almost, if not totally, insurmountable task because of how committed we are historically and culturally to that idea.

So is white supremacy insurmountable? Can we boil it down to that?

Yeah, let’s put it that way.

No, I would never say that. I think what I said in Between the World and Me is that it’s likely to be with us through the rest of this country’s history. I do believe that’s quite likely.

Can you pick apart what’s different about those two?

I mean, insurmountable implies a kind of certainty. Look, anti-Semitism is what, 2,000 years old, 2,000-plus years old, whatever? Can Europe say it’s free of anti-Semitism? After two millennia of struggle with it?

No, not at all.

So what fucking right does America, or even us who are doing the work here in America, have to presume that we most certainly will be free someday of racism? That’s what I object to. Because I think you deeply understate the challenge that’s faced. This is a country that would not exist without slavery.

It’s in the bones, do you understand what I’m saying? It’s in the economies, it’s in the cultures, it’s in the politics, it’s everywhere. So, just to stick with this example of anti-Semitism, note that the greatest crime of anti-Semitism happened almost 2,000 years into the history of it. So I don’t think that it’s crazy to say that when you’re looking at our country, for some 250 years, a quarter of a millennia, it tolerated the enslavement of people. It tolerated the doctrines that justified that enslavement. It tolerated the culture, it tolerated the politics. Then what followed was an era of pogroms, of Jim Crow, of massacres, of death, of robbery, of raping. And what followed that? An era of mass incarceration where we built the largest prison state ever known to man and we built it on the basis of racism and white supremacy. Dude, this is huge. What good does it do a doctor to act like cancer isn’t a big deal just because he hopes for a cure?

One thing I’ve heard repeatedly from activists I’ve talked to is the need to believe victory is possible.

They’re not wrong. They just have a different job than I have.

Do you think they’re deluded, though?

No, I wouldn’t say that, either. I would never say that.

Is your stance that it’s sort of an unknowable?

When I came to New York City, I wanted to be a writer who could support his family and take care of his family, whose work people respected. I was a college dropout. I had an 11-month-old child. I had no discernible income. The only income in my house was made by my then-partner, now wife, who was making about $29,000 a year. We were living in the basement of a brownstone. If it was somebody’s job to assess, do you think this guy is going to become this celebrated writer? And he said no, I couldn’t really be mad at them for doing that. Now me, myself, who’s out here in the struggle at that time? I had to believe in myself. I had to believe in that beyond whatever empirical evidence might’ve been there in the first place. I know this is a bit of a tortured metaphor. What I’m trying to say is, people who are actually out there doing the work, I understand why they need to believe.

This article was originally published by the Intelligencer.

A version of this article appears in the November 25, 2019, issue of New York Magazine.