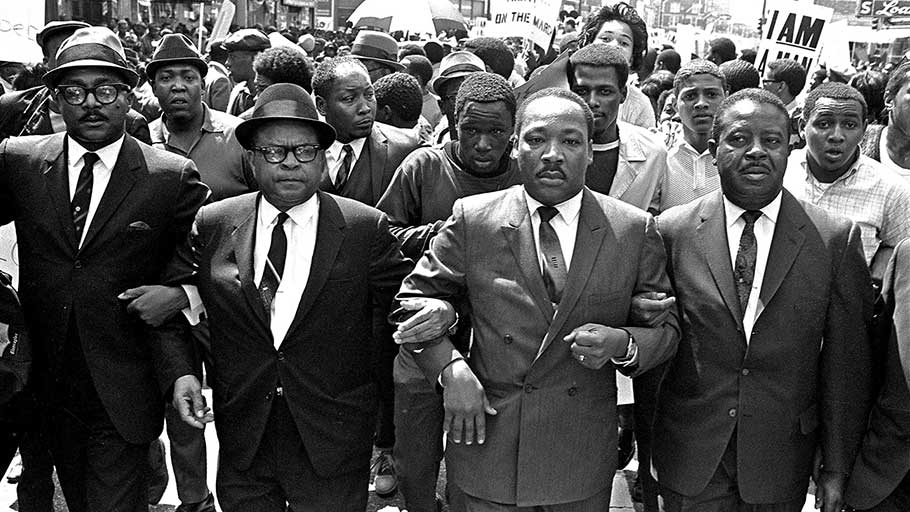

Martin Luther King Jr. in Memphis, Tennessee, 1968. (AP / Jack Thornell)

By Robert Greene II, The Nation —

Gone was the optimism of 1963. It had been replaced by a sense of disillusionment, a sense of urgency that America was about to lose the last chance to have its soul.” This was how Jet magazine described the climax of the Poor People’s Campaign, which reached Washington, DC, in the tumultuous summer of 1968. For Jet and for many early civil-rights activists, the Poor People’s Campaign marked a frustrating epilogue to a movement that had captured the nation’s attention in the first half of the 1960s and come to a frustrating pace of change in its second half. Slowed by white backlash and political exhaustion, civil-rights leaders hoped the Poor People’s Campaign might give new energy to the radical visions of emancipation they had helped popularize, but for many in the movement’s rank and file, it felt like a desperate last cry rather than the beginning of a new phase in the struggle for racial equality.

King and the Other America by Sylvie Laurent, Foreword by William Julius Wilson

In her new book King and the Other America, historian Sylvie Laurent helps rescue the Poor People’s Campaign from this unfair reputation and makes a compelling case that it deserves to be not only better remembered but also more closely studied and emulated by the left today.

For Laurent, the Poor People’s Campaign was the start of a new phase of radical activism and egalitarianism. While it failed to achieve the kinds of concrete reform that the earlier civil-rights movement won, it did inspire a whole generation of radicals to take a more holistic look at how discrimination in American society worked, helping them forge a powerful critique of racial and economic inequality in America. The Poor People’s Campaign, she argues, was a critical turning point and yet also a missed opportunity.

King and the Other America helps make another important argument. Situating the economic egalitarianism of the Poor People’s Campaign and Martin Luther King Jr.’s later years in a far longer history of black activism and social-democratic thinking, she helps map out the deeper intellectual and political roots of an entwined racial and economic egalitarianism that has been at the center of much of African-American politics for nearly a century. By doing so, Laurent offers us an elegant and timely history of how black intellectuals have long made a case for the intersections between class and race. Building on the work of Thomas F. Jackson, whose pioneering From Civil Rights to Human Rights redefined the history of King’s relationship to the social-democratic left in American history, Laurent helps us connect King’s vision of social democracy to a black political tradition that has always put economic inequality at its center.

To tell her story, Laurent begins not with the Poor People’s Campaign and its origins but goes back considerably farther, to the post–Civil War efforts by African Americans to achieve economic self-empowerment in the Reconstruction years. It is here, she argues, that one can find the origins of an intersectional egalitarianism and the roots of what become the Poor People’s Campaign and MLK’s social-democratic views.

During Reconstruction, various attempts at land ownership by African Americans were only the most prominent examples of black people trying to take control of their economic destiny. Frederick Douglass, for example, repeatedly pressed for the economic empowerment of recently freed black people, as well as the necessity of their uniting with poor whites across the South. Likewise, in an example often glossed over (and not mentioned by Laurent), South Carolina’s legislature also took on the project of economic redistribution. The most radical of the Southern legislatures during Reconstruction, it created a commission that redistributed land from former slave owners to anyone willing to pay taxes and interest for it over the course of several years. Open to any resident of South Carolina, the Land Commission’s offer was taken up primarily by black people, as white citizens boycotted the Radical Republican state government. Although it was ended by a Democratic regime in 1890, the Land Commission proved to be the only significant attempt by a state government to follow through on the promise of Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman’s “Forty acres and a mule” special order in 1865.

King’s turn toward economic radicalism had other antecedents as well, and Laurent spends a considerable amount of time on them, especially W.E.B. Du Bois. Seeing the ravages of the Great Depression further damage the precarious economic condition of African Americans, Du Bois urged the consolidation of what little black economic power there was in the 1930s and ’40s, whether through cooperatives or other self-help agencies. Indeed, Du Bois had long had an interest in cooperatives, having written a book in 1907 titled Economic Cooperation Among Negro Americans. By the 1930s, he had added an incisive critique of how race and class intersected in American society and insisted that the only way to defeat racism was through cross-racial working-class solidarity. This was an argument central to Black Reconstruction in America, as well as in many of his other writings from this period.

By the 1930s, Du Bois was not alone in making the case that black emancipation would come only through shared class and material interests. A. Philip Randolph’s push for a march on Washington in 1941 called for a federal guarantee on defense-industry jobs for African Americans and was inspired by Randolph’s socialism and his insistence that the fight against economic inequality was central to the struggle against racism. The famous 1963 march that Randolph’s idea inspired—the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom—also represented his and many others’ effort to tie economic and racial egalitarianism together.

The civil-rights movement always kept a close eye on the economics of racism. Many of the great clashes of the civil-rights era remembered today—the Montgomery bus boycott, the Albany movement of 1961–62, the Birmingham campaign of 1963—had links to local struggles over black economic empowerment. As Laurent notes time and again in the exhilarating first chapters of King and the Other America, civil-rights leaders learned from left-wing activists how to agitate for civil and economic rights, seeing the two as inextricably linked.

An examination of King’s ideological foundations forms a large part of Laurent’s book. She acknowledges that his ideological worldview cannot be easily pinned down: It was not just socialist or Christian or anti-imperialist; often it was all three at once and tending to draw from a medley of different sources, centered on the potential of American democracy and his principled stance against racism and imperialism in American society. King also had a loosely socialist analysis of American inequality that became more pronounced as the years went on. While he was not what Laurent calls a “procommunist Marxist,” he did use a Marxist analysis of political economy to build his critique of capitalism in the United States and to understand the ways race relations had been formed in the South.

King’s socialism influenced his answer to the problem of racial inequality in America, too. A reckoning with racism, he insisted, was impossible without radically redistributing wealth and, by extension, power in American society. His analysis of the riots of the mid- to late ’60s, which took place primarily in Northern and Midwestern cities, cemented this argument for him. “A riot is the language of the unheard,” King insisted at the height of that “long, hot summer”: For him, race, class, and economic empowerment were therefore all intertwined in these urban rebellions. Civil rights and voting rights were critical for African Americans, but King recognized that in places outside the South, where African Americans had practiced the power of the ballot for decades, economic power was also a necessity for black emancipation.

Historians have long contended that King’s left turn, coming in the late 1960s, marked a radical break from his more liberal and integrationist politics in the 1950s and early to mid-’60s. But Laurent compellingly shows how King’s increasingly outspoken views on economic inequality were simply a case of him making public the views that he already held privately and that he felt he could no longer keep private after years of witnessing the appalling poverty in both urban Chicago and rural Mississippi. After the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, King was already insisting that it was only the first stage in the struggle for black freedom. Without a frontal attack on economic inequality, political and civil rights were not enough.

By offering a prehistory of King’s economic politics, Laurent convincingly demonstrates how thinkers like Du Bois and Randolph influenced King and how their critiques of American capitalism flowed from even older intellectual and political traditions that were at the bedrock of black politics. For Du Bois, Randolph, and King, their mixture of racial pride with an understanding of the need for cross-racial solidarity to fight entrenched economic interests was not something new but long in the making.

Another of the strengths of Laurent’s book is the seriousness with which she treats progressive efforts to construct a more just and inclusive vision of America in the 1970s and ’80s. Placing King in conversation with intellectuals like Kenneth Clark, Gunnar Myrdal, and Michael Harrington, she helps bring the history of racial and economic egalitarianism into the years after King’s assassination.

While some of this political and intellectual history has been covered elsewhere, what makes Laurent’s work so valuable is the way she situates the activism of the 1970s and ’80s in the context of King and earlier struggles for racial equality. The Poor People’s Campaign, with its calls for massive government spending on a domestic “Marshall Plan,” helped sustain the visions of economic and racial equality into an age of increasingly conservative politics. The 1966 Freedom Budget proposed by Randolph, King, Bayard Rustin, and other leaders in the civil-rights movement helped inspire the efforts to sustain and protect social democracy in America in the 1970s and ’80s. As King wrote in his foreword to the Freedom Budget, it signified “a moral commitment to the fundamental principles on which this nation was founded.”

In addition to reminding us of all this useful history on the issue of economic inequality, Laurent does an excellent job delineating the challenges that often made assembling a multiracial coalition on behalf of the poor and working class in the United States so difficult. Her chapter “A Counter-War on Poverty,’” on what happened with the Poor People’s Campaign when it arrived in Washington, is a case in point. In it, she discusses how the tensions between the leaders of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference and those representing Latino, Native American, and poor white activists threatened to derail the campaign. Latino activists like Rodolfo Gonzalez and Reies Tijerina criticized the Poor People’s Campaign for its treatment of nonblack denizens of Resurrection City, and cross-racial solidarity turned out to be a powerful ideal often difficult to put into practice.

Yet the multiracial coalition and the campaign held together. The common experience of poverty and economic disempowerment often proved an essential elixir of interracial and class tensions, and one cannot help but wonder if the Poor People’s Campaign might have persisted into the 1970s and ’80s had King and Robert F. Kennedy, another prominent supporter of the campaign, not been gunned down in 1968.

Jesse Jackson’s presidential campaigns of 1984 and ‘88 came closest to reviving its vision, adopting a New Deal–like social-democratic politics in the mid-1980s, while building a wide-ranging and multiracial coalition to support it. But neither campaign broke out of the Democratic primaries and into the general election.

We would do well to recall the promise and learn the lessons of the Poor People’s Campaign today: A true multiracial coalition of working people in the United States will require an understanding of the unique historical experiences of the various racial and ethnic groups involved in order to achieve genuine gains for all. We cannot gloss over the differences in these experiences, but we cannot move forward without building a coalition that transcends them.

Recent debates about the need for reparations have opened another front in the long-lasting argument about whether social-democratic reforms will work for all Americans or, inevitably, leave the least of us behind, in particular those suffering from structural forms of racial inequality. King’s words have been used in support of reparations, with an oft-retweeted video of him talking in 1968 about the need for economic restitution to African Americans in the same vein as the aid to white farmers in the 1860s under the Homestead Act.

The creation of the act, with its associated funding of land-grant colleges, was in King’s view a worthy model that could be followed to help African Americans gain economic parity with other racial and ethnic groups. “Now, when we come to Washington, in this campaign,” King thundered, “we are coming to get our check.”

But the fact that King said this to a largely black audience in the Deep South while putting together his Poor People’s Campaign should give pause to anyone who argues that there is some kind of either/or at work between reparations and social democracy. Any political debate about reparations or broader social-democratic reforms will ultimately have to reckon with how King, Rustin, Du Bois, and many others found ways to make arguments for a politics specific to the inequalities experienced by black Americans and a politics that could also appeal to everyone. All pushed for the recognition of the unique historical and modern circumstances of African-American economic weakness, as well as the need for cross-racial solidarity to solve these problems.

The Poor People’s Campaign remains a clarion call for today’s left. One can make the argument for a social-democratic America and for those forms of justice that specifically address the violence and brutality of American racism. Perhaps for this reason, Laurent is not the only one recovering its importance and King’s social-democratic views. The recent collection of essays To Seek a Newer World, edited by Tommie Shelby and Brandon M. Terry, and the books of Michael Honey have also closely analyzed King’s relationship to the labor movement in Memphis, Tennessee, and have helped illuminate his social-democratic vision. Likewise, a latter-day Poor People’s Campaign has been launched by the Rev. William J. Barber II of North Carolina. As Barber explains, the new campaign seeks to highlight the issues facing poor and working-class Americans of every color by building a diverse grassroots base, bringing together “white women from the coal mines of West Virginia…with black women from Alabama.” This is precisely the kind of coalition that King fought for in 1968—and that we so desperately need in 2019.

Robert Greene II is a PhD candidate in history at the University of South Carolina and has previously written for Jacobin, In These Times, and Dissent.