While it’s widely believed that Howard University came to be known as “The Mecca” in the 1960s, new evidence shows the nickname is more than half a century older than that.

By Jamaal Abdul-Alim, The Conversation —

If you ask just about anyone at Howard University what’s the other name for their school, they will readily tell you: “The Mecca.”

The name has been extolled by former students, such as acclaimed author Ta-Nehisi Coates, who wrote in his 2015 book “Between the World and Me” that his “only Mecca was, is, and shall always be Howard University.”

But ask anyone in the Howard community how and when the school came to be known as The Mecca – a question I’ve been researching for the past year – and blank stares are mostly the response.

Vice President Kamala Harris, then a U.S. senator, speaks at Howard University in 2019. Manuel Balce Ceneta for the Associated Press

In a 2019 article, The New York Times tried to find the origins of the use of the term for Howard when U.S. Sen. Kamala Harris, one of the school’s most well-known alumnae, was still a 2020 Democratic presidential candidate.

Greg Carr, an associate professor of Africana Studies at Howard University, told the newspaper that the term “emerged after the Civil Rights Movement.”

“In the wake of the death of Malcolm X and in the spirit of the Black Power movement, students began to informally refer to the campus as ‘The Mecca of black education,’” wrote Bianca Ladipo.

It seemed intriguing to me as a longtime admirer of Malcolm X – and also as one who made the pilgrimage to the original Mecca in Saudi Arabia, as Malcolm famously did in 1964. Still, as a veteran education writer with an extensive history of covering historically Black colleges and universities – including Howard – I decided to dig deeper. My efforts were not in vain.

A new era

Using Howard University’s digital archives, I discovered that one of the earliest documented references to “The Mecca” is found in the Feb. 26, 1909, edition of the Howard University Journal, a student-run publication. This was – contrary to what The New York Times said about the term emerging after the death of Malcolm X in 1965 – nearly 15 years before he was even born.

My finding comes at a time when Howard, located in Washington, D.C., is entering a new era. Its new president, Ben Vinson III, a leading scholar on the history of the African diaspora, took the helm at the storied university on Sept. 1, 2023.

Thanks to a five-year, US$90 million Department of Defense contract, the school recently became the first HBCU to partner with the Pentagon to conduct research in military technology.

The university is also on a quest to attain R-1 status. R-1 is a classification level reserved for universities that grant doctoral degrees and also have “very high research activity.”

Going way back

Named after one of its founders, Union general and Civil War hero Oliver Otis Howard, the school opened in 1867 and was established through an act of Congress.

Its founders envisioned Howard as a school for educating and training Black physicians, teachers and ministers from the nearly 4 million newly freed slaves.

Malik Castro-DeVarona, a political science major and a former president of the Howard University Chess Club, unwittingly helped me discover how the school came to be known as “The Mecca.” He suggested that I look in the digital archive for The Hilltop, the campus newspaper co-founded in 1924 by novelist Zora Neale Hurston.

In my online search, I discovered a different digital archive: Digital Howard. There, I did a simple search for the term “Mecca” and got more than 400 results, including the one from 1909.

The meaning of ‘The Mecca’

Through my research, I discovered that over the years “The Mecca” has been used in different ways. It is most often meant to preserve Howard’s reputation as a beacon of Black thought.

That first reference from February 1909 came in an article written by J.A. Mitchell, a student who referred to Howard as a potential Mecca for young Black students. Specifically, Mitchell wrote: “Howard indeed bids well to become the Mecca, toward which the eyes of our youth will instinctively turn,” Mitchell wrote in the Howard University Journal.

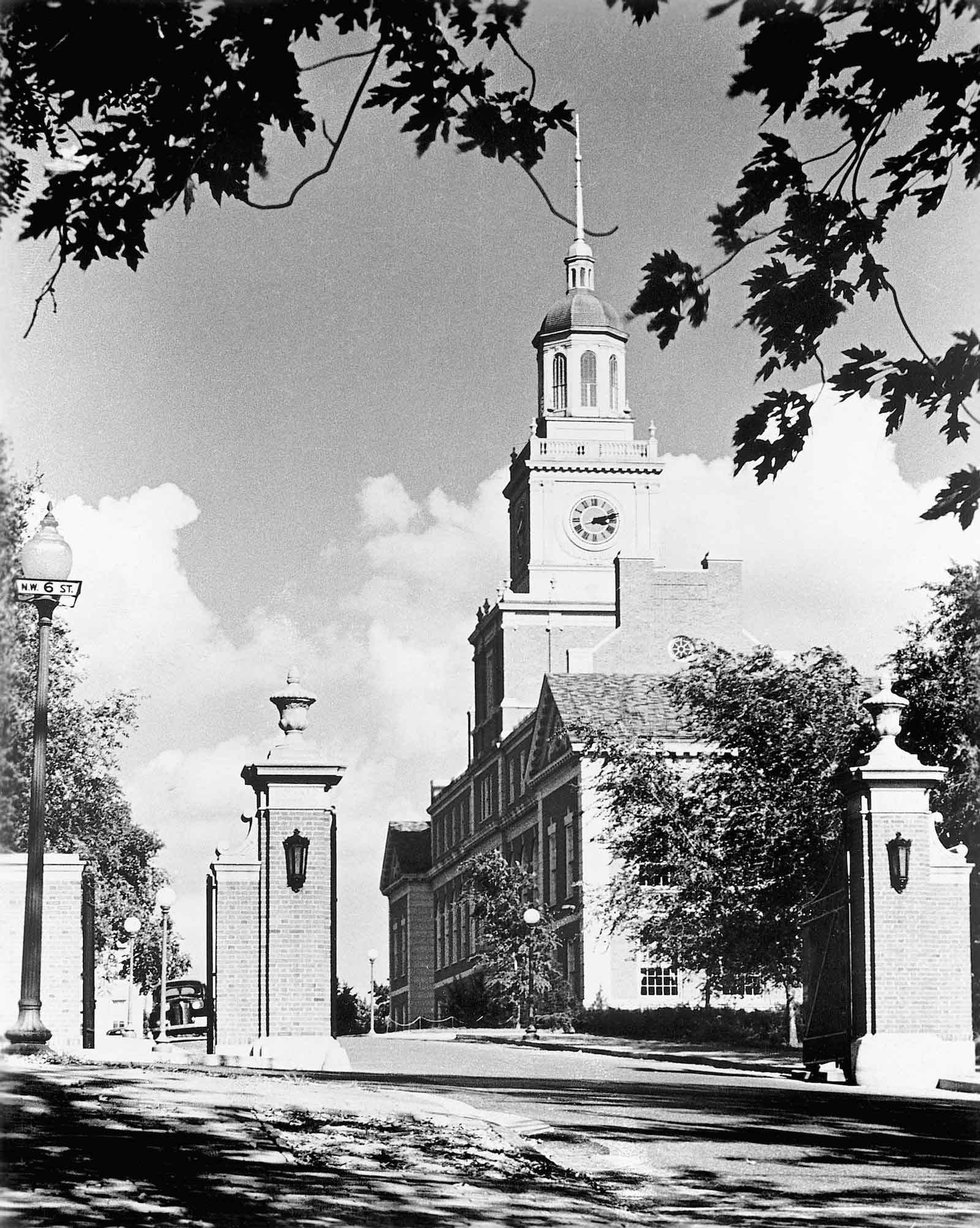

In this 1900 image, the exterior of Founders Library is seen at Howard University in Washington, D.C. Bettmann/GettyImages

“In fact,” Mitchell continued, “it seems as if the present outlook already forecasts a new era in the history of our school and tells of a future Howard, situated on a hill overlooking the national capital, that is second to no institution of its kind.”

That statement was prophetic. In its 2022 rankings, U.S. News and World Report ranked Howard as No. 2 among historically Black colleges and universities, making Howard second only to Spelman College, an HBCU for women, located in Atlanta, according to the magazine.

Mitchell’s reference was not the only one. A few years later, in a 1913 edition of the Howard University Journal, an article stated:

“Howard is a strategic institution. She is “The Mecca” of higher education attended in main by Negro youths. … She commands the interest of multitudes of people throughout the land and gives impetus to the life of thousands of alumni and alumnae. Again, she nurtures fifteen hundred select youths of a race.“

A different Mecca?

Anyone familiar with the culture at Howard knows there’s a long-standing rivalry between Howard University and Hampton University, located in Hampton, Virginia, over which school is ‶the real HU.” My research shows there might have once been a debate over which school is “The Mecca” as well.

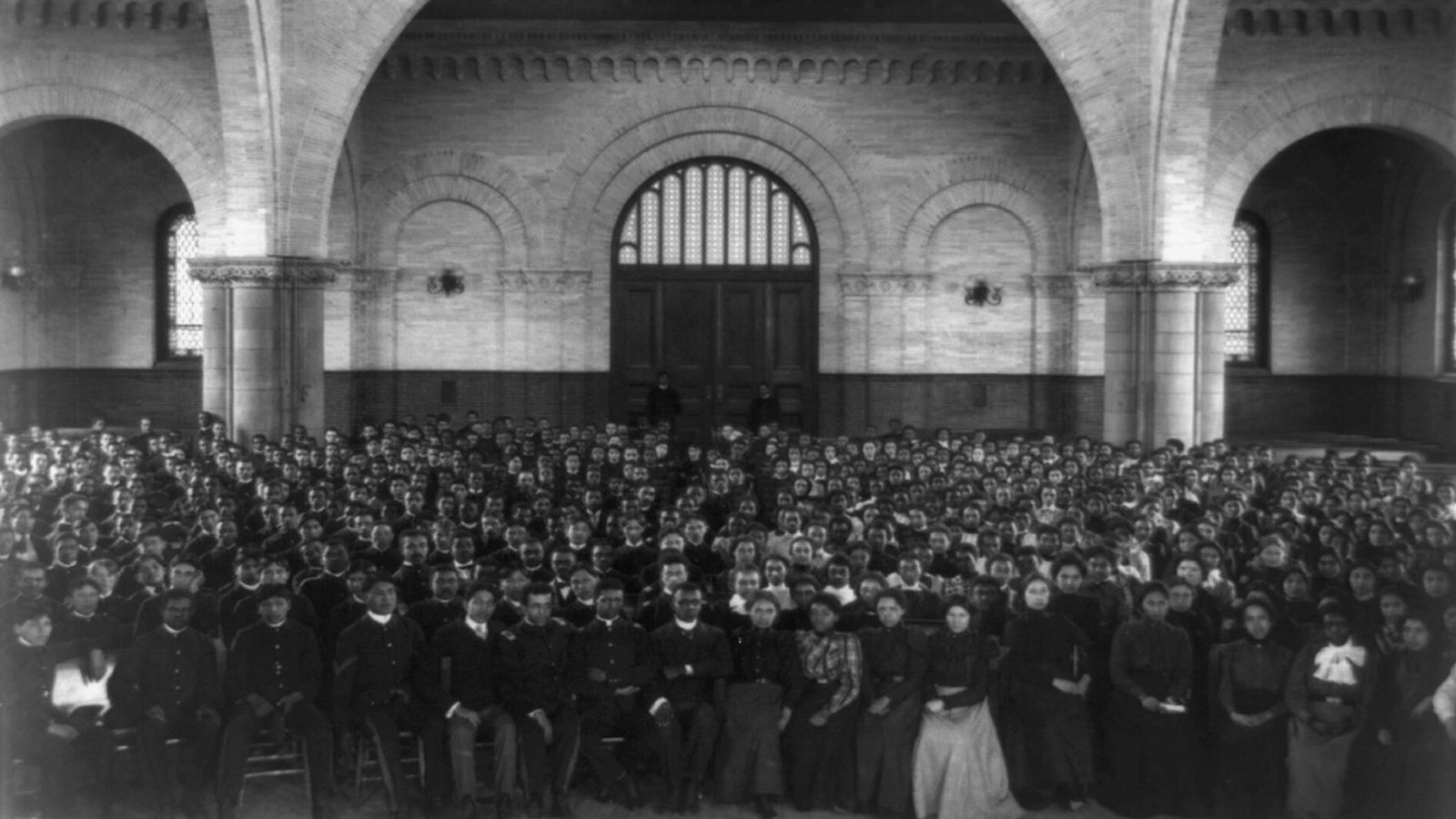

When Booker T. Washington arrived at Hampton in 1872 – five years after Howard University was founded in 1867 – Hampton, Virginia, was known as the “Mecca of the ambitious colored youth of the dismantled South,” according to a 1910 Howard manuscript titled “A Ride with Booker T. Washington.”

Students attend an assembly at Hampton Institute in January 1899. Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Hampton isn’t the only U.S. city to be known as a Black Mecca.

As noted in a 1925 edition of “The Crisis” – the NAACP magazine founded in 1910 by W.E.B. DuBois – Washington, D.C., was “regarded as the Mecca of the American Negro, for here he is under the wing of the eagle and can’t be made the victim of hostile legislation or rules.”

Around the same time, Alain Locke, who taught English and philosophy at Howard in the early 1910s and started the school’s philosophy department, proclaimed Harlem as the “Mecca of the new Negro.” Locke is also known as the “dean of the Harlem Renaissance.”

The point is this idea of a Black Mecca was constantly shifting and continues to shift to this day.

The Mecca of the future

Despite archival records that show Howard was called The Mecca as early as 1909, other details have yet to be discovered. Perhaps under the leadership of President Vinson, a champion of digital scholarship, Howard students and scholars can continue to research how Howard came to be known as The Mecca.

Doing so would be a fitting tribute to one of Howard’s most illustrious deans, Carter G. Woodson.

Hailed as the “father of Black history,” Woodson launched Negro History Week in 1926. That paved the way for what today is known as Black History Month.

Source: The Conversation

Jamaal Abdul-Alim has served as a volunteer adviser for the Howard University Chess Club. In addition to his role as an adjunct at the University of Maryland, he currently serves as education editor at The Conversation.

Featured image: Howard University students assemble for a graduation ceremony in 2016. Jose Luis Magana for the Associated Press