In the classroom, historical events that happened more than a century ago can still prompt difficult conversations about race and inequality.

The ongoing debate over what students across the country should learn about United States history has been fiery. My colleagues spoke to seven social studies teachers about how they run their classrooms, what they teach and why. Mary Suh, our education editor, Kassie Bracken, a senior video journalist, and Jacey Fortin, an education reporter, shared their insights on how this project came about and how they approached their reporting. Their answers have been lightly edited for clarity.

Mary: As many schools and school boards fend off attacks over their approaches to U.S. history — with critical race theory used as a rallying cry — we began to wonder: What is actually being taught in U.S. classrooms? How do teachers talk about the Civil War or Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings, an enslaved woman who bore Jefferson’s children?

With nearly 100,000 public schools in the United States, there really isn’t a single answer to that question. So much depends on teachers in the classroom. We decided to ask a group of teachers about how they addressed these issues, their approach to U.S. history and what they thought of the political debates now engulfing education.

Kassie: This assignment was a challenging but exciting opportunity: How do you provide insight into hundreds of thousands of classrooms through the voices of seven teachers? As I watched and read through much of the coverage of the debates over C.R.T., the voices of teachers felt absent.

Organizations like the National Council for History Education and the Bill of Rights Institute were especially helpful in connecting me with teachers. But I quickly learned there is a robust network of social studies teachers on social media, and teachers referred me to their colleagues and friends across the country.

As I spoke with dozens of teachers by phone, clear themes emerged. Already exhausted from teaching through a pandemic, many felt further demoralized by the new legislation and school board attacks. As Mike Klapka, a teacher of 40 years in Florida told me, “I’ve never seen such attacks upon us — they want to change us from professional educators to assembly-line workers.”

But in addition to better understanding what it’s like teaching in this politicized moment, we wanted to know what and how they were teaching, especially when it came to tough conversations around race and inequity.

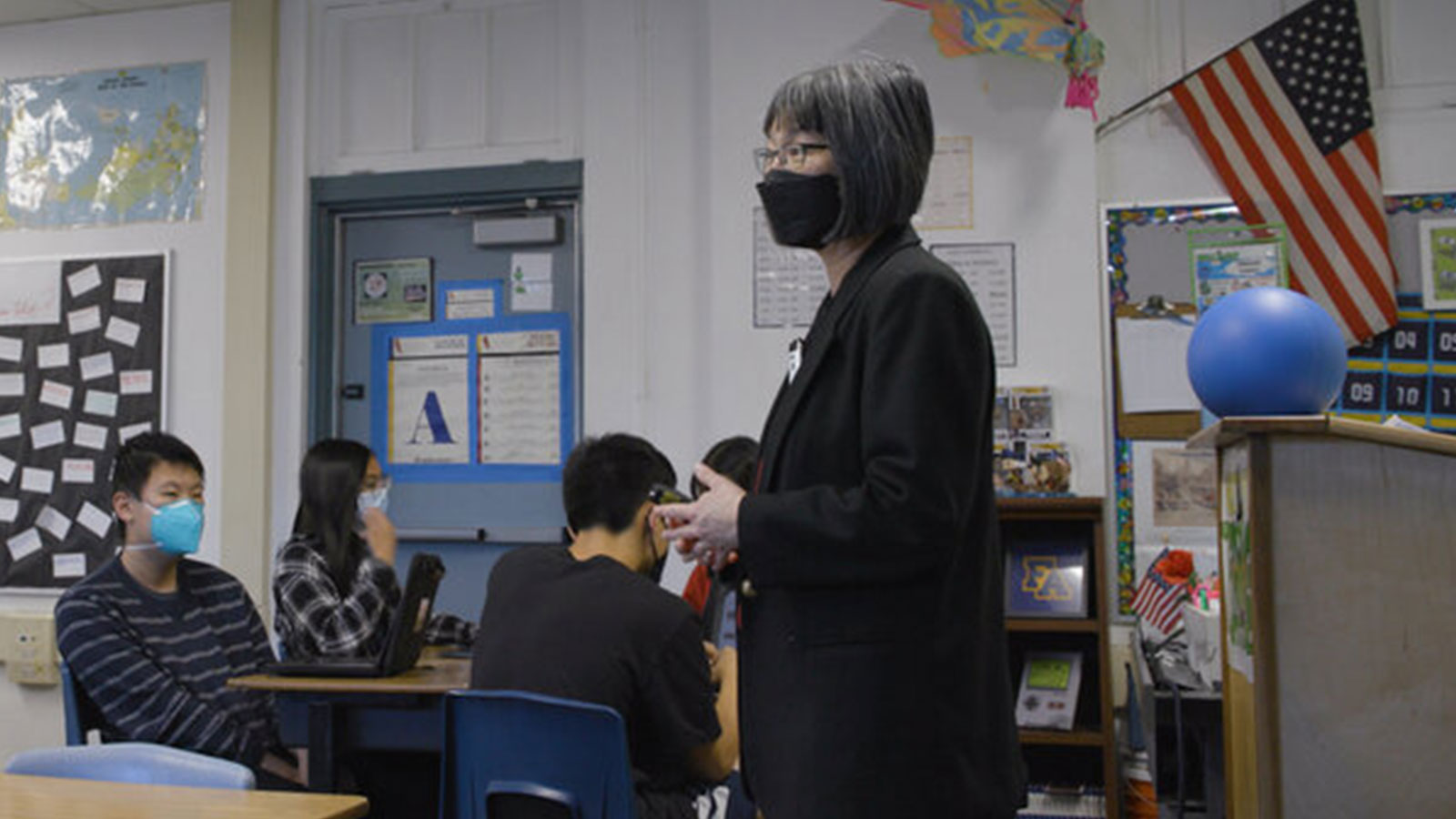

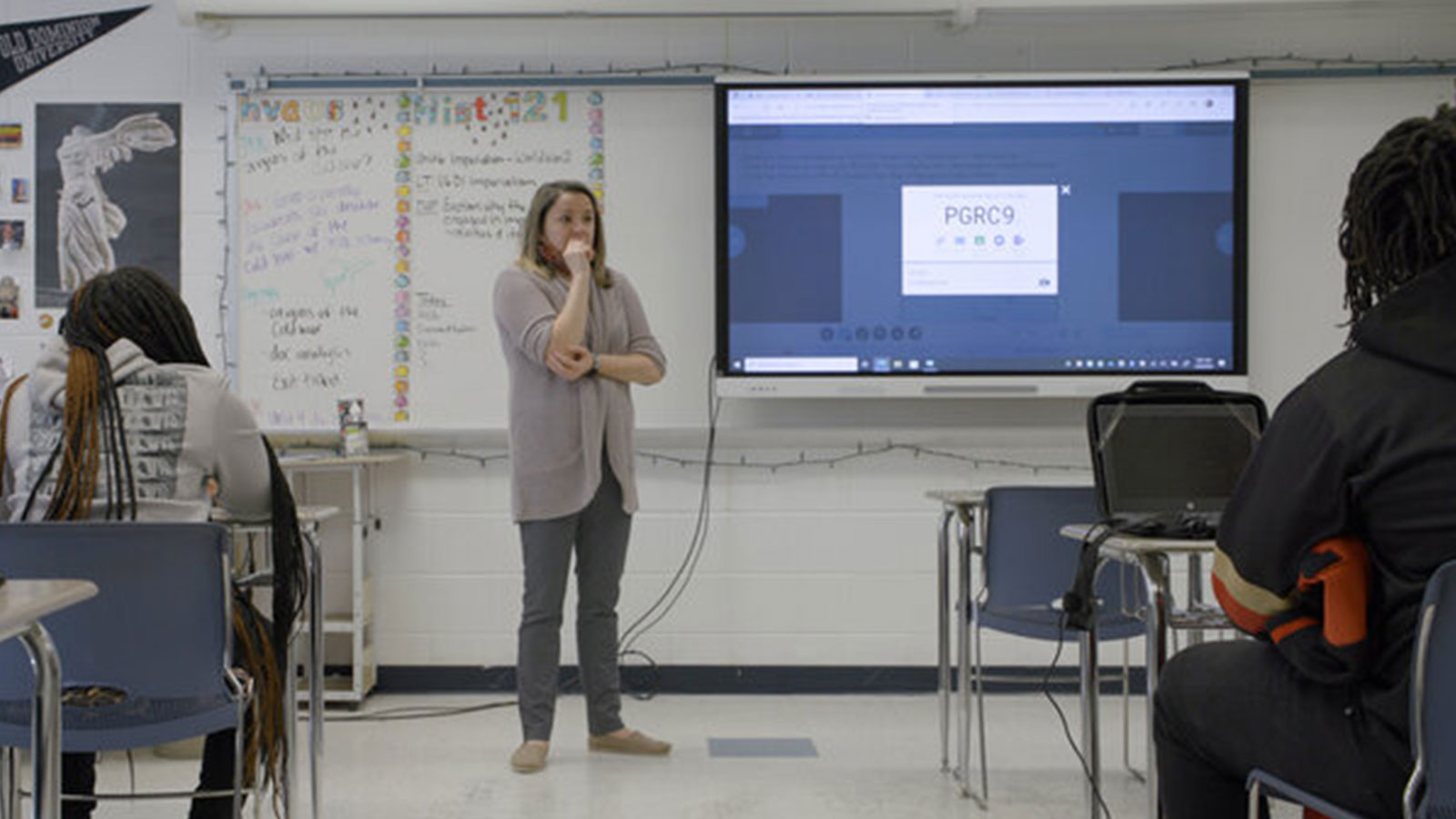

Educators said that some of the most interesting classroom discussions were driven not by politicians, parents or teachers, but by students. (Noah Throop/The New York Times)

Social studies teaching has changed since I went to high school in the 1990s. I was surprised to learn that nearly all of the teachers I spoke with said they rarely used a textbook. Instead, they provided their students with primary source materials.

We devoted a section of our questions to concrete historical periods, events and figures to get a sense of the variety of approaches to these subjects. Some questions: What do you teach about how the founding fathers considered race in the development of the country? What do you teach about Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings? What do you teach about the causes of the Civil War?

While curriculums guides teachers, lessons and conversations are shaped by personal philosophies and lived experience. These also play a role in how teachers value representation and amplifying voices of marginalized people often left out of history.

In Arcadia, Calif., Karalee Wong Nakatsuka’s eighth-graders research, write and deliver eulogies for Thomas Jefferson’s enslaved people. In Gettysburg, Pa., Alisha Sanders has her students complete a version of a 1964 literacy test that was presented to would-be voters in a Louisiana parish.

In Pennsylvania, where Alisha Sanders teaches civics, Republican officials introduced a bill last year to restrict classroom discussions about race and gender. It was not passed by the legislature. (Noah Throop/The New York Times)

They varied on their beliefs as to whether their job included instilling a sense of patriotism in their students. A few underscored the importance of creating empathy within the classroom. While some teachers steered away from current events like the murder of George Floyd or the Jan. 6 attack on the U.S. Capitol, some like Shane Phipps in Indianapolis felt it “would be criminal to ignore” them.

As Michael Hjort, an Advanced Placement U.S. history teacher in Texas, shared with me about his students: “Normally on the first day of school I tell them there are going to be days that you’re going to swell with pride. And there’s going to be days that you’re going to want to go home and take a shower,” he recounted. “Right there I get chills, because that’s U.S. history.”

Jacey: Telling stories about what’s happening in public schools is tough because every classroom is different. It’s not really possible to make broad statements about how teachers do their jobs. That’s why video was the perfect medium for this project; it allowed educators to speak for themselves, and it allowed us to see that they do not always agree with each other.

I wrote the words you see on the screen, but Kassie was the one who traveled to all of these states and conducted every interview. My contribution involved verifying some of the things the teachers were saying about U.S. history, which had me tracking down historical documents about Thomas Jefferson, browsing encyclopedia entries about Reconstruction and interviewing a civil rights activist who worked in Louisiana in the 1960s.

Reporting on critical race theory is always difficult, because conservative activism in recent years has warped its meaning. As these teachers make clear, it is a graduate-level academic framework — not something that public school educators are teaching to children and teenagers. But it’s also clear that the framework has had an influence on the study of history more broadly, and that there are teachers who agree with some of its most basic premises about the social construction of race and the persistence of structural racism. To say that teachers do or do not teach critical race theory is to miss a lot of that nuance, and it was interesting to hear the teachers talk through all of that, each in his or her own way.

What these videos make clear is that teachers do not work in a void. They are talking to, and with, students. Students have opinions, and they ask questions. They can read the news, and they have access to social media.

Source: The New York Times

Featured image: By Noah Throop/The New York Times