Solomon Plaatje, an early ANC leader, came to America in 1921 to expose the growing number of race laws back home.

A short, well-dressed 44-year-old man of the southern African Barolong tribe stood at the American border near Niagara Falls holding Canadian passport No. 79551. It stated the bearer was a British national and a resident of Toronto. In fact, he was Solomon Plaatje, the first secretary-general of what would become the African National Congress — the party Nelson Mandela would later lead, and the party that would eventually overthrow South Africa’s old racial order.

Plaatje was headed to the U.S. for a series of speaking engagements intended to spread the word about alarming new segregation laws being passed back home. Just how he persuaded Canadian officials to issue him a phony passport is lost to history. In his recollections, he simply notes: “I crossed the border about noon and reached Buffalo.”

[ White Americans ] Speak to Me Precisely as if the World Had No Such Thing as Color — Solomon Plaatje, First Secretary-general of the African National Congress.

The previous year, 1920, Plaatje had written to American social activist and author W.E.B Du Bois, stating he might not be able to meet him because South African authorities “had the measure of me.” Indeed they did. Edward Barrett, the South African secretary of native affairs who withheld Plaatje’s passport, described the ANC leader as “a troublesome professional agitator” whose lectures in the U.S. would “no doubt consist of mendacious attacks” on the South African government.

Mendacious, unlikely; clever, certainly. Plaatje was an autodidact of prodigious talents. Educated at a remote German missionary school to the level of a 13-year-old, he was fluent in seven languages by age 18. He went on to translate Shakespeare and author one of the first novels written in English by a Black South African, Mhudi. He started his career as a postman, but by 1921 he was well-known in South Africa and Britain as a writer, newspaper editor, politician and activist.

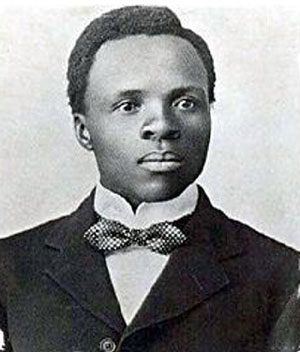

Solomon Plaatje

If allowed in the U.S., Barrett believed Plaatje would ally himself with the “mischievous activities” of a fellow traveler — Marcus Garvey, a leading American proponent of Black nationalism. Although Plaatje shared the stage with Garvey at a sold-out Liberty Hall in New York, Black nationalism was not on Plaatje’s agenda. He fervently opposed a separate-but-equal solution to the race question. Instead, he, like his lifelong friend Du Bois, fought for racial equality under the law. Plaatje was hugely influenced by his meetings with African-American intellectuals and with Du Bois in particular, whom he took “as a model for black modernity,” says Laura Chrisman, a professor of English at the University of Washington.

Few records of Plaatje’s tour of the U.S. remain. Brian Willan, author of Sol Plaatje: A Biography, uncovered a report in the publication Negro World stating the South African held his audience “spellbound” during a lecture in Brooklyn. A faded poster broadcasts Plaatje’s upcoming appearance on March 13 at the Bethel AME Church in Harlem to give “a thrilling account of the condition of the Colored Folk in British South Africa.”

Despite traveling widely — Washington, D.C., the Hampton Institute (now Hampton University) in Virginia, Booker T. Washington’s Tuskegee University in Alabama and elsewhere — Plaatje’s overall impressions of America are preserved only in a letter to an English friend. In the missive, he marvels at his white traveling companions in a Pullman railroad car. “Should South Africa ever get Pullman carriages of this type,” he wrote, “the Jim Crow Act No. 22 of 1916 would prohibit a Native from looking into one, except perhaps as a cleaner.” In the same letter, he noted with amazement that white Americans “speak to me precisely as if the world had no such thing as color.”

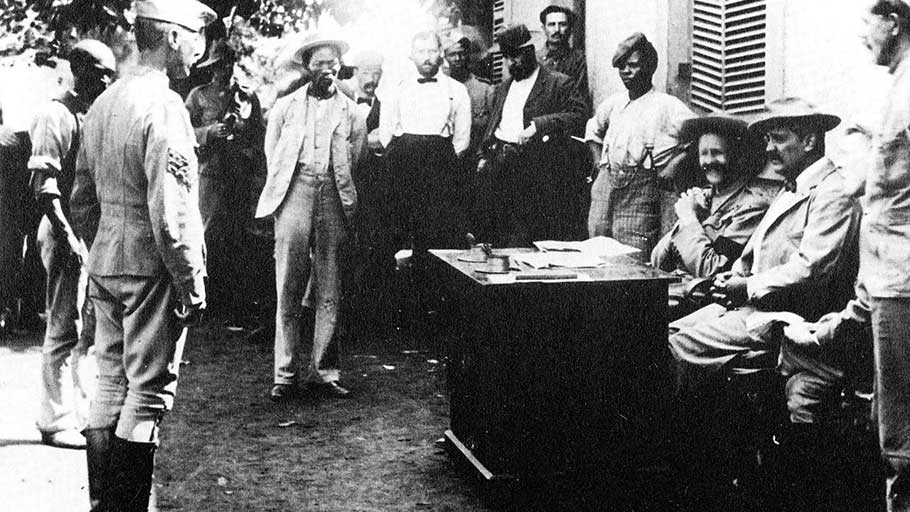

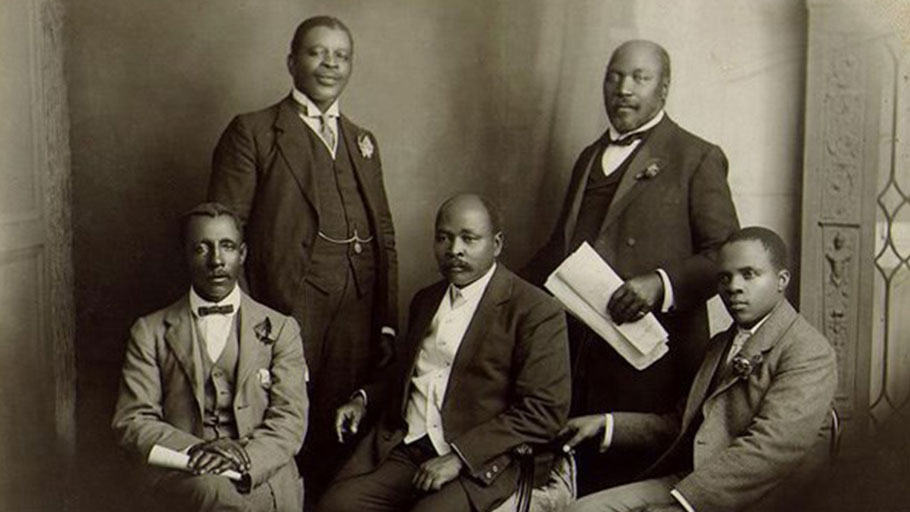

The South African Native National Congress delegation to England, June 1914. From left: Thomas Mapike, the Rev. Walter Rubusana, the Rev. John Dube, Saul Msane and Solomon Plaatje.

Plaatje was not blind to inequalities in the U.S.; he recorded the segregation in the South. But the book he had written — the volume he carried everywhere, Native Life in South Africa — noted South Africa’s Native Lands Act of 1913 apportioned only 7 percent of the country’s arable land to Blacks, who represented 80 percent of the population. As Plaatje told American audiences in packed halls and churches, this relegated Blacks to a position of “semi-slavery.” They could neither buy land nor build their own halls, shops and churches.

As he later wrote, he often heard racists in America stating that “the Negro” should be kept in “his proper place.” But, in a typical piece of wit, he noted that in South Africa there was no “place” left for Blacks “to be kept.” Even this had been taken from them by the white government. “The Native,” Plaatje wrote, had awakened on June 20, 1913, “to find himself a pariah in the land of his birth.”

Plaatje returned home in 1922 to continue the fight against racism. But he arrived with a sense that South Africa was on a diametrically opposed trajectory to that of the U.S. The South African government was drawing up additional race laws — and there would be a great deal more to come. He went to see an old white friend, the politician Henry Burton. But, as biographer Willan notes, the friendship now seemed “almost out of place.”