Black History Month lessons have been ‘stagnant’ for years, educators say. Here’s how some teachers are trying to change things.

Freshman year can make anyone feel lost, but Seattle teen Janelle Gary felt especially lost when she entered high school in 2015. At home, she watched a wave of gentrification drive change in the historically black Central District neighborhood, and at school, where she was one of the few students of color in an honors history class, she felt as if black perspectives were also in the minority.

Looking back at that time, as now-18-year-old freshman at Central Washington University, she feels her teacher was “tip-toeing” around hard race-related questions about history. But things were different in her Ethnic Studies class, where her teacher Jesse Hagopian remembered what it was like to be the only black kid in a class.

That memory — and the lasting impact of a college class that looked at race head-on — is part of the reason why Hagopian, 41, and other educators inspired by the Black Lives Matter movement organized a national Black Lives Matter at School Week of Action. What started locally in Seattle in 2016, inspired by a federal investigation into the higher rate of suspensions of black students compared to their white peers, has grown into a nationwide organizing effort.

In 2020, for the second year in a row, teachers — including in the country’s three largest school districts, in New York City, Los Angeles and Chicago — will wear “Black Lives Matter” shirts to school as they teach lessons on black history and race issues from Feb. 3 to Feb. 7. The organizers are also calling for Black History and Ethnic Studies to be a graduation requirement in K-12 schools.

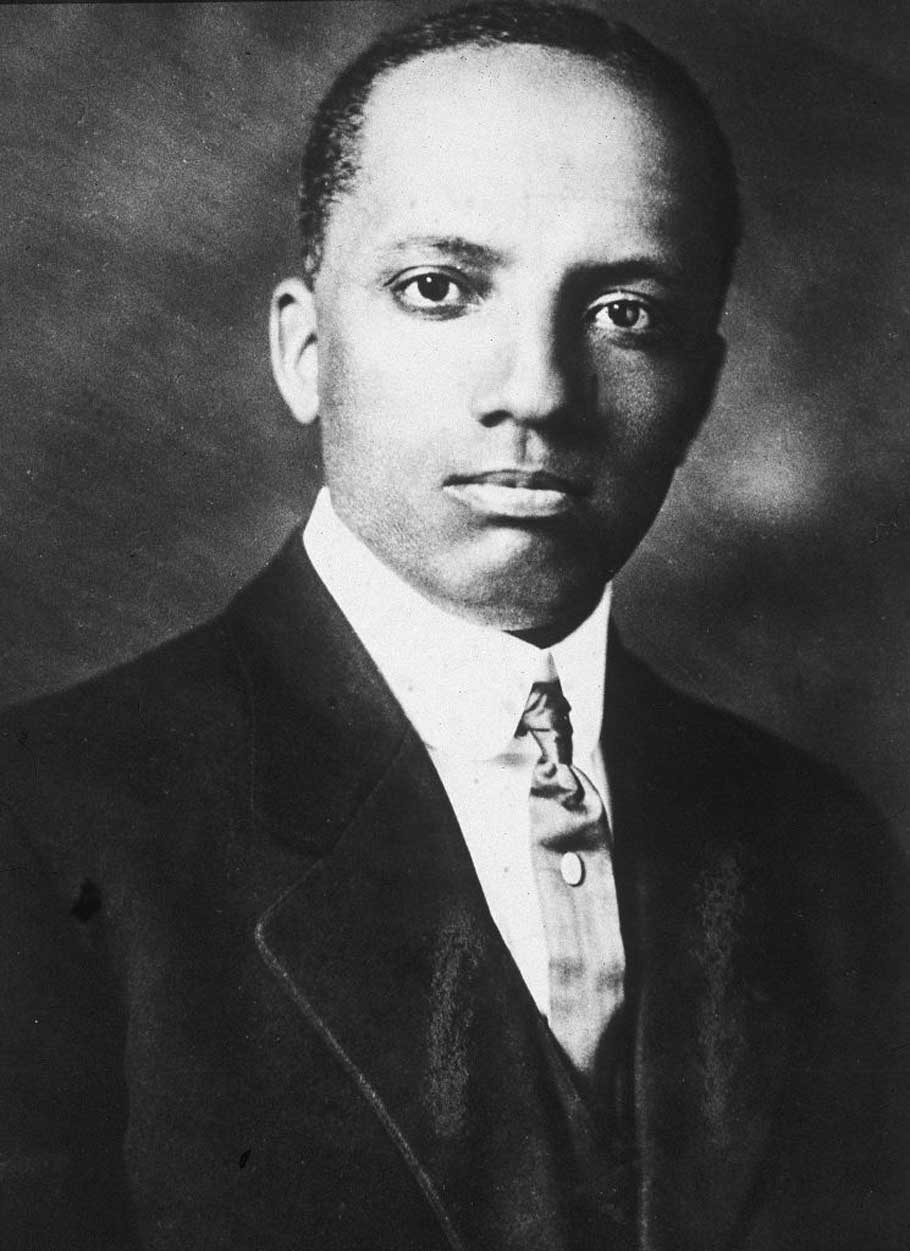

Theirs is not a new call to action. They are driven by the same feeling James Baldwin described in 1963: “I began to be bugged by the teaching of American history, because it seemed that history had been taught without cognizance of my presence.” It is also the same feeling that in 1926 drove Carter G. Woodson, who is known as “the Father of Black History,” to urge educators to set aside a week in February “for the purpose of emphasizing what has already been learned about the Negro during the year”; what he started became Black History Month in 1976.

And yet, from that old feeling, they are helping Black History Month — and the year-round teaching of the topic — evolve to a new stage.

“I definitely think that Black Lives Matter encouraged people to learn about other movements that came before,” says Tatiana Amaya, 19, a freshman at Claremont McKenna College who took a required black history course in her Philadelphia high school. “It’s central to understanding that black oppression still exists today.”

The Origins of Black History Month

Carter G. Woodson knew about history. After all, in 1912 he became the second African American to earn a PhD in history from Harvard, after only W.E.B. DuBois. So he could see that history was being distorted — especially, in 1915, by The Birth of a Nation. The enormously successful movie painted a white supremacist vision of the American past, and inspired a resurgence of the Ku Klux Klan.

The movie came out that February, and that September Woodson founded the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History, now the Association for the Study of African American Life and History.

“You had this understanding from the historical profession, from popular media, from literary works, that African Americans have no history, and if they are written about in history, it’s not something that is respectable,” says Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham, chair of the History Department at Harvard University and the current National President of the Association for the Study of African American Life and History. “Woodson started an organization, and literally a movement that exists to this day to correct those lies.”

A circa -910s portrait of historian and educator Carter G. Woodson. Hulton Archive, Getty Images.

While black people had been educating each other about their history for decades, vital new textbooks came out in the years that followed, such as Woodson’s The Negro in Our History (1922) and, later, John Hope Franklin’s From Slavery to Freedom (first published in 1947). Woodson’s Negro History Bulletin also circulated to churches and public schools. The civil rights movement of the ’50s, ’60s and ’70s led to further growth of this discipline, even inspiring student walkouts calling for black history classes, and the social movements of that period led to a shift toward teaching that history through the stories of ordinary people who laid the groundwork for larger change. By the time Black History Month was formally declared in 1976, the Black Power movement had fueled a new emphasis on “what’s unique about being a black person in America,” says Higginbotham.

And many educators say that, just as a moment of crisis for African Americans fueled Woodson’s original vision, this moment in time is proving to be a new turning point for black history as a discipline.

“Whenever there’s a tragedy in black America, there’s always been an uptick of black history courses, most recently [with] Black Lives Matter and police shootings,” says LaGarrett King, Professor of Social Studies Education and Founding Director of the Carter Center for K12 Black History Education at the University of Missouri. Social media has fueled discussion among teachers on how to contextualize these current events, such as Twitter hashtags like #FergusonSyllabus, #CharlestonSyllabus and #CharlottesvilleSyllabus, and teachers say that current events have piqued students’ interests, especially after Colin Kaepernick’s kneeling during the national anthem.

“I have spent so much time talking about Black Lives Matter over the last two years and I’ve had to weave Black Lives Matter into my lectures on various topics because students — both K-12 and college level — heard about the movement,” says Keisha N. Blain, a historian who co-founded the #CharlestonSyllabus, “and they wanted to figure out how does this connect to what happened in the ’60s or even earlier.”

Black History in the Classroom

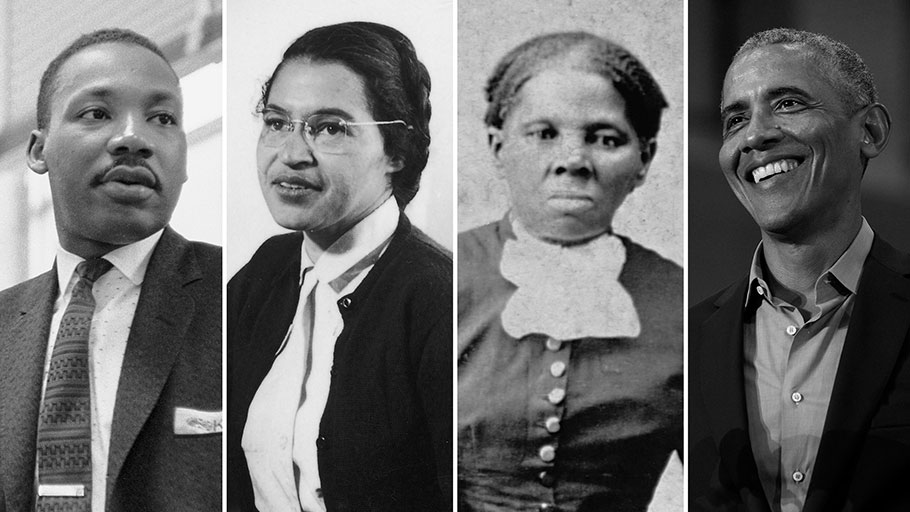

But for the most part, educators say, K-12 students who do learn about black history are hearing about the same few historical figures over and over: Martin Luther King Jr., Rosa Parks, Harriet Tubman and former President Barack Obama. While those lives are undoubtedly worthy of study, they do not exist in a vacuum.

That’s why LaGarrett King describes the state of the teaching of black history in schools as “steadily improving, yet still stagnant.”

“One of the problems with getting black history right is we are still trying to use this notion that black history is American history, which sounds good,” says King. But, he says, that creates a problem when American history is taught, as it often is, as a story in which “every generation has improved our society.”

The problem with that perspective can be seen, for example, in the teaching of the 20th century civil rights movement, which tends to be where black history ends in many American schools, says Christopher Busey, a University of Florida professor who has researched Black History in social studies standards. When the narrative ends at the victories of the Civil Rights Act and the Voting Rights Act, it can be hard for students to make the connection between that optimistic ending and the problems of today. “When we have more contemporary movements such as Black Lives Matter, people are largely unable to make sense of it because we skipped the war on drugs with Reagan and the targeting of black communities by police,” he says. “Their last conceptions of black citizenship are tied to this idea that we all had a dream, we overcame, and Obama was elected President.”

In addition, black stories often end up told through a white lens. Stories of black people resisting white supremacy in any way other than nonviolent protest may be left out, while the study of oppression can crowd out the study of African contributions to society, from the libraries and intellectual life of Timbuktu to the earliest calendars and forms of mathematics.

“If the first time that black people enter the school curriculum is through when they’re enslaved,” says King, “that gives the impression these particular people were not that important to American democracy and didn’t contribute to the intellectual development of the country.”

Paradoxically, while slavery and the civil rights movement may be the most recognizable black history subject areas, the quality of what students are learning about these topics has come into question recently. A 2018 survey by the Southern Poverty Law Center found that only 8% of high school seniors could identify slavery as the main cause of the Civil War. The same organization produced a 2014 “report card” on state standards and resources on the teaching of the history of the civil rights movement nationwide, and gave 20 states a failing grade. The biggest issue across the board was “sanitized” history, including resources that made it sound as if civil rights was just a Southern problem, and a lack of sufficient discussion about the hard realities of the violent resistance to the movement.

Toward a New Curriculum

Now, however, there are signs of change. Many people in the mostly-white U.S. teacher population haven’t taken a dedicated course in black history and are learning as they go, but Ursula Wolfe-Rocca, 44, a white high-school social studies teacher who teaches black history lessons year-round at a predominantly white school district in the Portland, Ore., area, says it’s crucial that educators become better equipped to teach the subject. Otherwise, “it reinforces the fundamental flaw, which is that black history is seen as peripheral,” she says. “The answer to why do white kids need black history is that it is history and it’s their history too. It’s a shared collective past.”

Seven states launched commissions designed to oversee state mandates to teach black history in public schools in recent years, and Illinois requires public colleges and universities to offer black history courses. To meet the rising demand for resources, at least six Black History textbooks are on the market, as well as lesson plans on websites including Teaching Tolerance, Teaching for Change, Zinn Education Project and Rethinking Schools. (The most-downloaded lessons from the Zinn Education Project website for most of 2019 were about Reconstruction.)

In 2005, Philadelphia became the first major American city to require students to take a black history class to graduate. Confining black history lessons to February, as many schools do, is “the exact opposite” of what Woodson envisioned, says Greg Carr, Chair of the Department of Afro-American Studies at Howard University, who led the team that developed the Philadelphia curriculum.

In addition, to give students more perspective on black experiences worldwide, an Advanced Placement seminar on the African Diaspora, developed by Columbia University’s Teachers College, the University of Notre Dame and Tuskegee University, is being piloted in 11 schools in the 2019-2020 year, up from two in 2017-2018 school year. There are also lesson plans available based on Henry Louis Gates Jr.’s 2017 PBS documentary Africa’s Great Civilizations.

Data on the impact of learning African and African-American history are hard to come by, but there are already indications that new curricula are making a difference for some students. In the 2018-2019 school year, for example, 80% of students — including under-performing students — in five schools that offered the AP African Diaspora pilot passed, according to Kassie Freeman, who played a key role in developing the seminar and is a senior faculty fellow at the Institute for Urban and Minority Education at Teachers College and President of the African Diaspora Consortium.

Some of the impact is harder to quantify, but no less real.

After taking Philadelphia’s required class in 9th grade, Maye-gan Brown, now a 22-year-old Muhlenberg College senior, realized “how much we center black men when it comes to civil rights,” she says. “A lot of the time we left out women like Fannie Lou Hamer.” Since Philadelphia teacher Abigail Henry, 36, started organizing mock trials on subjects such as whether George Washington “promoted the institution of slavery,” she’s noticed that students who are usually quiet and withdrawn have earned some of the highest grades. Makaia Loya, 17, a student in Denver, says it was a lesson about Malcolm X’s 1964 speech “The Ballot or the Bullet” that reshaped her career goals: “I grew up thinking, ‘I’m getting as far as I can from the ghetto,’” she says, “and now I’m like, as soon as I Ieave and have something to bring back, I’m coming back.” And Pascagoula, Miss., senior Kinchasa Anderson, 18, says that a field trip last fall to Medgar Evers‘ house in Jackson, Miss., gave her a new appreciation for how that history affects her life today.

“It just struck me — these people really put their life on the line for us,” she says, “for my generation, for generations to come.”

And in that feeling, these students are themselves part of the connection between history and lived experience. As Jeanne Theoharis writes in The Rebellious Life of Mrs. Rosa Parks, Rosa Parks’ political awakening began at a young age, when she learned what an understanding of black history could do.

“The revelation of black history would indelibly shape Rosa McCauley Parks’s life,” Theoharis writes. “She saw the history of black survival, accomplishment, and rebellion as the ultimate weapon against white supremacy.”

This article was originally published by TIME.

Featured image: For the most part, educators say, K-12 students who do learn about black history are hearing about the same few historical figures over and over: Martin Luther King Jr., Rosa Parks, Harriet Tubman and President Barack Obama. Getty Images (4).