By Fay Horwitt, Lanessa Owens-Chaplin and Trevor Smith

Pop culture has made Tulsa, Oklahoma, and the violence that destroyed its Greenwood community the center of conversation in ways that it never has been before.

The HBO series “Watchmen” kicked off with a vivid re-enactment of the massacre. The comic book series “Bitter Root” features the massacre as its heroic characters fight racism.

But Greenwood wasn’t the only Black Wall Street in America, and mass violence wasn’t the only means of wiping them out. Urban renewal and redlining tore apart many Black neighborhoods, along with their promises of progress and economic freedom.

Ottawa W. Gurley, who founded Greenwood, was worth nearly $5 million in today’s money. And a dollar recirculated among Greenwood’s businesses (banks, theaters, stores, hotels) 36 times before leaving that 35-block Tulsa neighborhood.

The recent push to “buy Black,” and an episode of the documentary series “Trigger Warning with Killer Mike,” shows just how difficult it is to find, live in and support Black businesses today. The rapper tried to survive for three days buying just Black goods and services. He wanted to learn “how to reconnect my community.” Killer Mike was exactly right when he said, “This country is better when the Black community is strong.”

But he struggled in 2019 to complete a challenge that was very possible in 1921, before Tulsa’s destruction. He had to sleep on a park bench (couldn’t find a Black-owned hotel while on tour) and concluded that money today recirculates among Black businesses for just six hours.

After centuries of racial violence, displacement, segregation and a lack of investment, the idea of a Black Wall Street – where businesses and entrepreneurship can thrive and money can continue to support it – is a near impossibility.

How many Black Wall Streets were there in America? It’s hard to know.

Here, we take a look at three – Durham, North Carolina’s Hayti community; Richmond, Virginia’s Jackson Ward; and Syracuse, New York’s 15th Ward. These neighborhoods weren’t desecrated by mob violence and massacres. Instead, they were ripped apart by state development.

Hayti community

Hayti (pronounced HAY-tie) was founded in in the mid-19th century by freedmen looking for work. Parrish Street and the surrounding blocks became home to more than 200 Black-owned businesses.

Jim Thornton/The Herald-Sun File photo, from March 1, 1965, shows a portion of the Hayti community that was cleared out during Durham’s Urban Renewal project.

The community owed much of its success to the leadership of Black multipreneur John Merrick, who launched one of the nation’s first Black-owned insurance companies, the North Carolina Mutual and Provident Association.

W.E.B. Du Bois once noted the advanced level of Black entrepreneurship, stating that “there is a singular group in Durham where a Black man may get up in the morning from a mattress made by Black men, in a house which a Black man built out of lumber which Black men cut and planed; he may put on a suit which he bought at a colored haberdashery and socks knit at a colored mill; he may cook victuals from a colored grocery on a stove which black men fashioned; he may earn his living working for colored men, be sick in a colored hospital, and buried from a colored church; and the Negro insurance society will pay his widow enough to keep his children in a colored school. This is surely progress.”

By 1920, the community’s worth (including businesses and property) was more than $51 million in today’s money.

That prosperity would last another few decades, before the community was divided by Highway 147, permanently displacing hundreds of residents, cutting the community off from downtown Durham and leveling the heart of Hayti’s business district.

Jackson Ward

In 1903, Jackson Ward resident Maggie L. Walker, the daughter of former slaves, became the first woman to charter a bank in America — the St. Luke Penny Savings Bank.

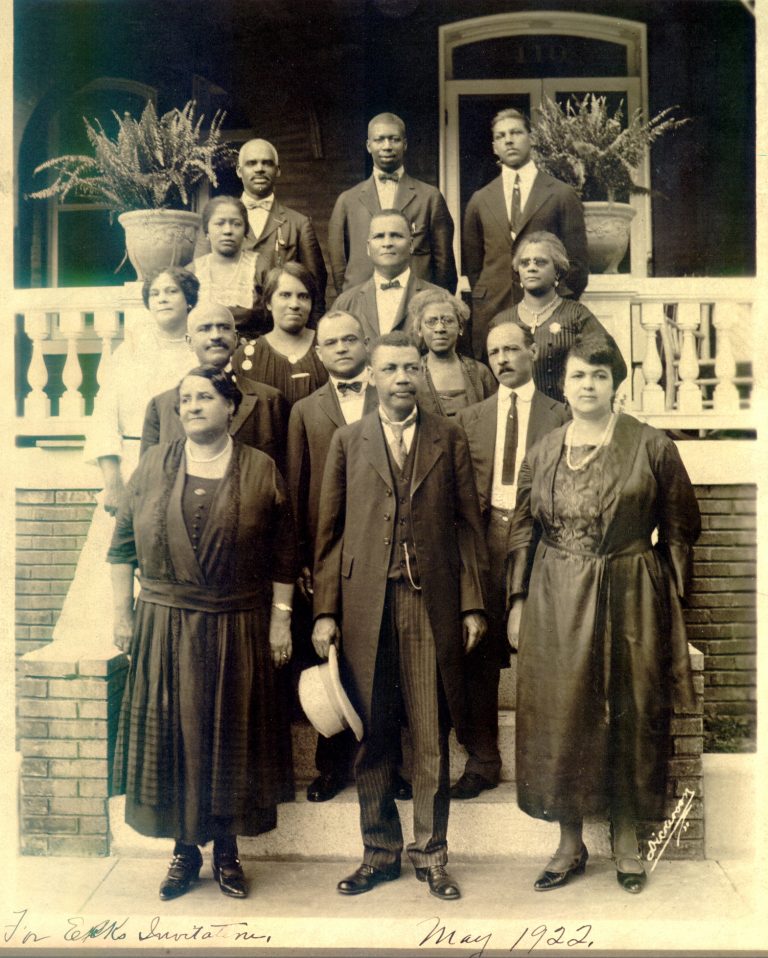

Maggie L. Walker, bottom left, and others in front of Walker’s Jackson Ward home, May 1922. National Park Service

Through the bank and a subsequent department store, Walker leveraged entrepreneurial ventures to combat the oppressive conditions of racial segregation while encouraging economic independence and thrift in the Black community. She shared her bold vision for the bank in a local convention speech in 1901: “First we need a savings bank. Let us put our moneys together; let us use our moneys; let us put our money out at usury among ourselves, and reap the benefit ourselves. Let us have a bank that will take the nickels and turn them into dollars.”

Jackson Ward became a vibrant center for Black business and entertainment, earning another moniker, “Harlem of the South.”

In the 1950s, the Richmond Housing Authority’s urban redevelopment plans included the construction of a highway that damaged Jackson Ward’s economic and social structure. The Richmond-Petersburg Turnpike destroyed more than 1,000 homes, killing important pathways and what had been the neighborhood’s cultural center.

Urban “improvements” stripped Black businesses and residents of their property and hard-earned economic independence.

15th Ward

While not officially known as one of the original financial hubs for Black people after Reconstruction, Syracuse has historically been home to a vibrant Black community. In 1950, the 15th Ward housed 90% of Syracuse’s Black population.

The close-knit neighborhood included hundreds of families and Black-owned businesses. City leadership labeled it a “slum.”

In the late 1950s, the city ran the elevated part of Interstate 81 through the center of Syracuse, razing the 15th Ward and displacing families along with Black businesses.

Today, the median income for white households in the Syracuse area is nearly two times that of nonwhite households. Syracuse also has one of the largest racial poverty gaps of any metropolitan area in the nation, with nearly 40% of Blacks living below the poverty line – nearly 30 points higher than the city’s white poverty rate.

Repair, replicate and rebuild

Three core pillars of success in these historic examples can be replicated in today’s economy for even greater impact: the infusion of institutional capital, place-based clustering of Black-owned businesses and the intentional reinvestment of Black wealth back into the Black community.

As discussions within the Biden administration around infrastructure and the economy continue, it’s imperative that these plans address the history of displacement, engage in deeper conversations and work toward the amelioration of structural wealth inequality. The administration must also make investments in Black communities that allow them to regain ownership over local businesses and keep wealth within their communities.

File Photo from July 8, 1979 shows businesses being torn down, in the Hayti business district to make room for the East-West Expressway. Charles Cooper/The Herald-Sun

The administration must also ensure the land that becomes available when highways are torn down creates housing opportunities for Black communities and brings restorative justice and reparations for the wealth lost during the mass transit movement.

Land must be dedicated to Black communities that suffered property and business loss, while ensuring that anti-gentrification and anti-displacement measures are put in place. State and local governments should establish community anchors, giving preference to existing businesses or businesses started by longtime residents, adopting tax abatement and rent-control measures, and facilitating homeownership opportunities in their current neighborhood.

Long after the decimation of these Black Wall Streets, the wealth gap between Black and white households stands as stark today as it was in the 1960s, as white households have a net worth 10 times greater than Black households. The gap will only be closed through race-conscious policies, such as reparations, that seek to undo the harm of centuries of racialized violence and discrimination.

We must collectively acknowledge the reality that the historic growth of thriving Black business districts was not brought about by charity or verbal statements of support from the white community. Historically, Black wealth was built through catalytic investment in Black financial vehicles and property ownership.

We can look to modern-day Durham for examples of how today’s Black leaders are building back Black wealth. Black Wall Street Homecoming was established in 2016 by Black entrepreneurs as a three-day event that features Black-owned businesses, diversity initiatives and culture. The Black Farmers’ Market was launched in 2015 and now boasts biweekly events and created a Black farmers fund to help support their own trade union. Their goal is to continue to “expand self-sustaining Black marketplaces that help solve Black social and economic issues.”

Provident1898, a Black-owned and led coworking business founded in 2019, strives to create a space where the next generation of Black Wall Street-inspired, Durham born-and-bred entrepreneurs have clear pathways into acquisition entrepreneurship and the ability to expand self-sustaining Black marketplaces that help solve social and economic issues.

After breaking free from bondage, Black people were able to establish self-reliant cities, that allowed them to grow thriving businesses and create economic opportunity.

On this centennial of the brutal Tulsa riots, let’s remember other cities where Black wealth was decimated. In building the future of Black wealth, it’s important that we ground it in the history of its destruction.

Fay Horwitt serves as president and CEO of Forward Cities, a national nonprofit catalyzing equitable entrepreneurial ecosystems and re-imagining Black Wall Street as model and lever for economic mobility in a post-COVID economy.

Lanessa Owens-Chaplin is the assistant director of the Education Policy Center at New York Civil Liberties Union and leads the statewide environmental justice initiative.

Trevor Smith is a communications and narrative strategist who writes and researches on the topics of reparations and the racial wealth gap. He also works at the Surdna Foundation, a social justice reform organization.

Source: USA TODAY Discrimination, urban renewal killed Black Wall Streets outside Tulsa

Featured Image: Smoke rises north of Greenwood Avenue from Hartford Avenue, in Tulsa, Okla. on June 1, 1921. The University of Tulsa, McFarlin Library