Half a century ago, writer Wendell Berry saw this coming: What white people can’t talk about is destroying them.

Words matter; poetry has power. It’s not for nothing that authoritarians first go after the intellectuals, the journalists, the poets. Consider these well-wrought statements:

- All men are created equal

- Life, Liberty and the Pursuit of Happiness

- Liberté, égalité, fraternité

- Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere

- Black lives matter.

The first two you will recognize as having appeared in proximity with each other, in the second paragraph of the Declaration of Independence. All are connected concepts, and the final one hinges on your understanding and good-faith acceptance of the others, in their intent. (Yes, women were not mentioned, and, no, people are not born into life on an equal footing in many ways; politics is forever hamstrung by taking place in its own era.)

For a small but increasingly emboldened minority of contemporary Americans, the assertion that black lives also matter — the intended meaning, which was always obvious — was more than they could countenance. That this was so in the melting pot of the United States in the 21st century was in no small part due to a president who race-baited and championed white grievance (while, in his inimitable way, denying he was doing so: “I’m the least racist person there is anywhere in the world”), encouraging white supremacists to take off their hoods and take to the streets, reopening the country’s oldest wound.

From disingenuous reactions to discussions of white privilege to indignity at Colin Kaepernick taking a knee during the national anthem to decrying nonexistent violence by protesters of the killing of George Floyd to often hysterical fights over the teaching of “critical race theory” in schools, Republicans have been busy in their modern tradition of denying that race is an issue in America.

Half a century ago, in 1970, writer and environmentalist Wendell Berry realized that he felt a need to better understand, and come to terms with, growing up as a Southerner in a country that had enriched itself on an economy based on the buying and selling and brutal working of human beings:

It occurs to me that, for a man whose life from the beginning has been conditioned by the lives of black people, I have had surprisingly little to say about them in my other writings. Perhaps this is justifiable — there is certainly no requirement that a writer deal with any particular subject — and yet it has been an avoidance.

Those are the opening sentences from “The Hidden Wound,” the book that resulted from Berry’s remembrances of his childhood on his family’s farm in northern Kentucky. He recounts his family’s connections to slavery and speaks of the “mirror wound” that slavery and the Jim Crow era inflicted upon whites who engaged in it, supported it, mythologized it or simply looked the other way.

This wound is in me, as complex and deep in my flesh as blood and nerves. I have borne it all my life, with varying degrees of consciousness, but always carefully, always with the most delicate consideration for the pain I would feel if I were somehow forced to acknowledge it. But now I am increasingly aware of the opposite compulsion. I want to know, as fully and exactly as I can, what the wound is and how much I am suffering from it. And I want to be cured; I want to be free of the wound myself, and I do not want to pass it on to my children.

Berry writes, “Stories that have come down to me tell me that on both sides of my family there were slaveholders.” He recounts that some of these vague stories, the “hereditary knowledge” of the days of slavery, were told casually, usually without comment, as if it had been the natural and right order of things. If the behavior of a relation had been particularly egregious — Berry’s paternal great-grandfather had sold a slave, a man who resisted complete subjugation in numerous small ways — then “the self-defensive myth of benevolence” would be invoked. The victim, the dehumanized “bad n***er,” would be blamed, precisely as many Black victims of police brutality continue to be to this day.

Examining some of the myth-making and romanticizing utilized by writers to make the slave-owning history of the South more palatable, Berry quotes from the book “Kentucky Cavaliers in Dixie” (published in 1895 and, tellingly, reissued in 1957), whose author could be fairly objective about the horrors of the war but who would more often write “under the spell of chivalry and medieval romance.”

Speaking a public language of propaganda, uninfluenced by the real content of our history which we know only in a deep and guarded privacy, we are still in the throes of the paradox of the “gentleman and soldier.”

Berry also points out that the Southern man was “most fervidly” devoted to a separation of church and state because Christians felt the moral anguish implicit in racism and did not want members of the clergy, who typically attacked the institution of slavery, to have political power:

And so, beneath the public advocacy of the separation of church and state, an essential of religious liberty, we see working a mute anxiety to suppress within the government of the state such admonitory voices as might discomfort the practice of slavery. For separation of church and state, then, read separation of morality and state.

As to the separation of church and state, how things have changed for today’s politicians of the South, the modern Republicans. Pandering to their fundamentalist Christian voting bloc and sending conservative Catholics, one after another, to serve on the Supreme Court in order to strip women of their basic rights, is the order of the day.

The rest of “The Hidden Wound” is largely devoted to meditations on young Wendell’s relationship with Nick Watkins, a Black sharecropper in his 50s who worked for eight years for Berry’s grandfather, and a woman who lived with him, whom they called Aunt Georgie, following the Southern tradition of showing a superficial respect to Black workers among them. (The book is dedicated to them.)

The issue that an unfortunate number of white Americans had with the Black Lives Matter movement is that it — along with the protests and removal of Confederate monuments — broke through any “delicate consideration” they may have entertained about the state of race relations in this country. Led by their race-baiting president and conservative media “personalities,” they insisted that there was no such thing as white privilege and that “all lives matter,” perhaps some even thinking that statement was not disingenuous. (Yes, of course, all lives matter — but that was not the point being made.)

For many, especially Southern, white people, this is a subject that should not be broached or, especially, be considered in personal terms. After the Civil War it would be spoken of in only genteel euphemisms, like “the peculiar institution.” (The war itself, which took some 750,000 lives, was often referred to as “The Late Unpleasantness,” showing just how ardently Americans downplay reality.) It’s no wonder that people vehemently decrying the teaching of inclusion and diversity in the schools around the country, purposely mixing that up with the legal study of critical race theory, will shout or hold back sobs — as one woman did at a school board meeting in the very district my wife and I attended near St. Louis — and say some version of “Don’t you dare call me a racist!” None of us wants to think of ourselves in that way.

The issue that an unfortunate number of white Americans had with the Black Lives Matter movement is that it — along with the protests and removal of Confederate monuments — broke through any “delicate consideration” they may have entertained about the state of race relations in this country. Led by their race-baiting president and conservative media “personalities,” they insisted that there was no such thing as white privilege and that “all lives matter,” perhaps some even thinking that statement was not disingenuous. (Yes, of course, all lives matter — but that was not the point being made.)

For many, especially Southern, white people, this is a subject that should not be broached or, especially, be considered in personal terms. After the Civil War it would be spoken of in only genteel euphemisms, like “the peculiar institution.” (The war itself, which took some 750,000 lives, was often referred to as “The Late Unpleasantness,” showing just how ardently Americans downplay reality.) It’s no wonder that people vehemently decrying the teaching of inclusion and diversity in the schools around the country, purposely mixing that up with the legal study of critical race theory, will shout or hold back sobs — as one woman did at a school board meeting in the very district my wife and I attended near St. Louis — and say some version of “Don’t you dare call me a racist!” None of us wants to think of ourselves in that way.

It is much the same as how we and the mainstream media talk about this country’s endless state of warfare, and how we think of the victims of our wars. We don’t. “The Late Unpleasantness” is akin to how many Republicans, at most, tut-tut about the brutal Jan. 6 insurrection at the Capitol.

Thomas Jefferson, the man who crafted that touchy statement “All men are created equal” for the Declaration while still owning other human beings, considered that this “self-evident” truth would eventually work to put an end to slavery and allow all to pursue those lives, those liberties and that happiness he wrote of. It took a long time, but he was partially correct. Slavery was indeed abolished with the ratification of the 13th Amendment in December 1865, but Southerners simply replaced it with other forms of subjugation and purposeful injustice, including public murder at the hands of mobs. One should not forget that the first policing groups in the United States were slave patrols formed in the South to track down human beings who had escaped bondage. And, yes, that should be taught in schools. You may call it “critical race theory,” but it is not that; it is simply part of our history — unfortunately, still quite pertinent history.

The mythologizing of the war began before the first shots were fired. If you are asking men to fight, you must rouse their feelings of patriotism — in this case, not in fealty to the United States but to a new Confederacy, with a slightly but pointedly altered constitution, a new capital, at Richmond, Virginia, and rhetoric about Northern aggression. What was intended to be obfuscated in all the rousing and romanticizing and propagandizing about the reasons for secession was the fact that this was a call for citizens to renounce their own country, to take up arms and become traitors.

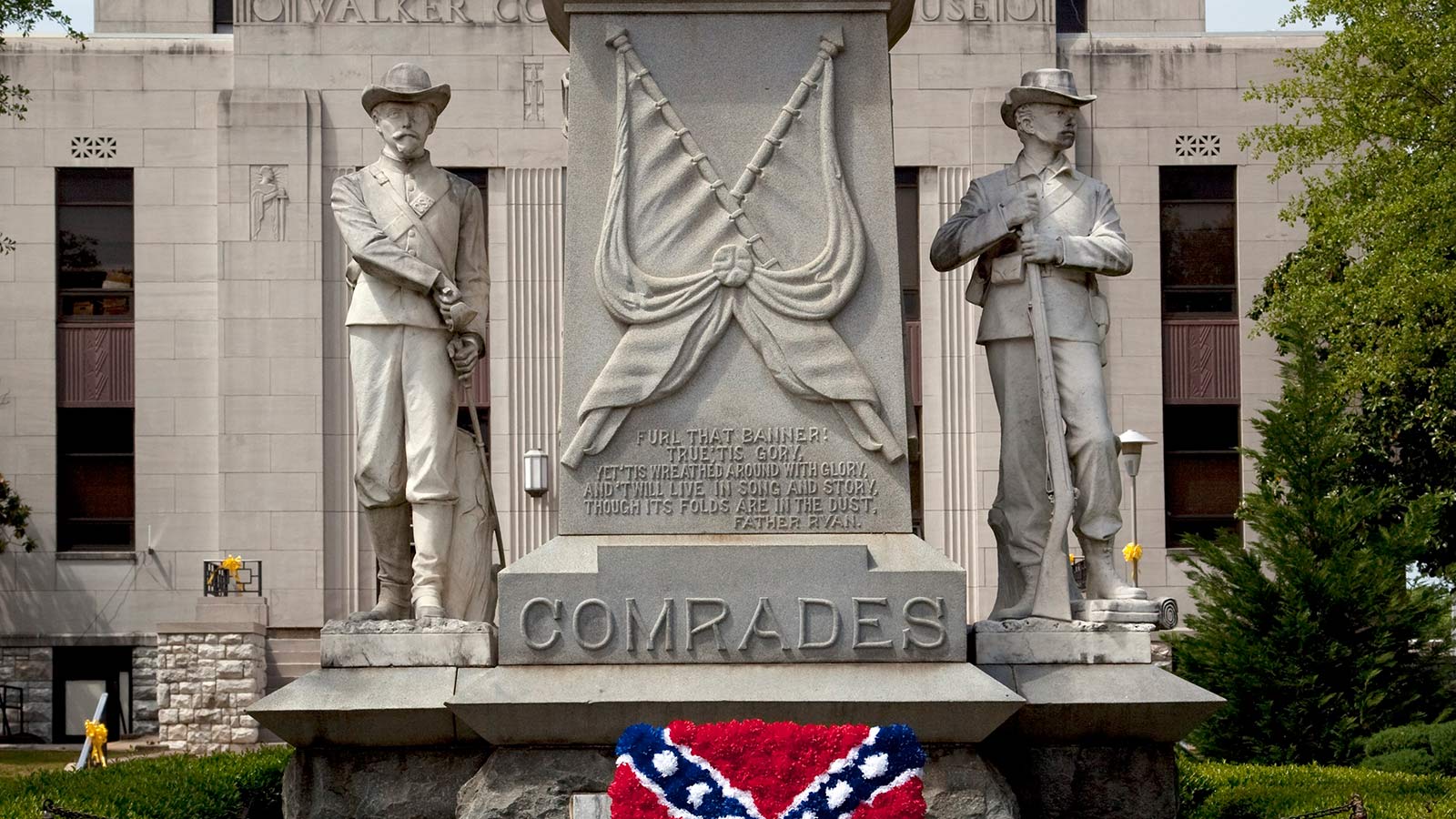

Here in St. Louis, a monument, “The Angel of the Spirit of the Confederacy,” which was presented to Forest Park by the Daughters of the Confederacy of St. Louis, had a bas-relief on one side of a man courageously shielding his family from some unknown (but clearly implied) harm. The year it was presented, 1914, is telling. All over the country a concerted effort was made to erect such monuments to the “Lost Cause” of the Confederacy — a revisionist myth that the states had left the Union not over slavery but in support of states’ rights. The monuments and the naming of schools for Confederate heroes were intended to create a heroic narrative about the South’s loss and to also send a clear message to Black Americans in the Jim Crow era.

You can take away the monuments (Richmond removed its famous statue of Robert E. Lee as I was writing this essay) and rename the schools, but how can we change the hearts and minds of people who have been inculcated with fear, whose attitudes today have become as hardened as that bas-relief and who are listening closely to leaders who are threatening renewed violence?

The avoidance that Berry invoked at the opening of “The Hidden Wound” is the key: It is easy for all of us to avoid the hard questions at any level. It is a human trait to procrastinate, to brush off small difficulties, to turn away from any level of personal examination. It is understandable, then, that it is painful and difficult to even glance at an enormous collective wrong such as how we as a nation could have allowed slavery, and then the injustices of sharecropping and segregation and redlining and the pain and suffering that followed, to exist — how we first denied humanity itself and then citizenship and then, grudgingly, doled out as little as was possible of the promise of America to Black citizens, even to those who had served their country. We offered second-class citizenship and denied opportunities to create generational wealth. (Speaking to the troll-minds out there for just a moment: No, I did not do that, and neither did you, but we did it collectively, as fellow countrymen and women. We are bound to our past, especially so if we refuse to examine it. As William Faulkner had one of his characters put it, “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.”)

It’s much the same as to coming to terms with our collective and individual responsibility for the degradation of the environment, another of Berry’s great concerns and something he touches on in this book. It is much easier — as consumers first and foremost, Americans are taught from birth to love what is easy — to deny the existence of climate change than to reckon with what it says about us, our individual personal responsibilities and our lack of care for future generations.

So one can claim we are not a racist country, but only by wearing blinders. We’re certainly better than we have been — we twice elected a Black man as president, and more Black students attend college than ever before — but parents need good jobs to keep families together, and children need access to excellent early education in safe environments. With only 10% of the average white family’s generational wealth, Black Americans can justifiably say that much of their journey forward has been a long march forward in the face of the same firehoses and snarling German shepherds some faced in the Deep South in the 1960s, but in the form quiet policies that work against them, in housing and banking and hiring.

With this retrograde white supremacist backlash from an extremist Republican Party, as a country we are now being asked to take many steps backward, with voting rights and with the overall tenor of our national discourse. As with the erection of those monuments to that fictional Lost Cause, the GOP is again sending a clear message to Black and brown Americans: We will do anything, even take down this democracy, to keep you a second-class citizen.

One remembers what Lyndon Johnson remarked off-the-cuff to Bill Moyers about the cynical politics in the South: “I’ll tell you what’s at the bottom of it. If you can convince the lowest white man he’s better than the best colored man, he won’t notice you’re picking his pocket. Hell, give him somebody to look down on, and he’ll empty his pockets for you.” If anyone knew about the inner workings of racism in the South, it was LBJ. When he became president, he mended his ways and, to honor the Kennedy legacy, championed civil rights. After he signed the Civil Rights Act of 1964, he famously remarked, “I think we just delivered the South to the Republican Party for a long time to come.”

We can continue to move toward being a more just society, but we need non-racist leaders to help get us there. Abraham Lincoln would not recognize today’s Republican Party — or rather he would recognize it, as the Southern Democratic Party of his era.

With a nod to his inspiration, Berry opens “The Hidden Wound” with this quote from “The Autobiography of Malcolm X“:

But I want to tell you something. This pattern, this “system” that the white man created, of teaching Negroes to hide the truth from him behind a facade of grinning, “yessir-bossing,” foot-shuffling and head-scratching — that system has done the American white man more harm than an invading army would do to him.

The hidden wound, not “black lives matter,” are the three words that threaten to bring down this nation again.

Source: Salon

Featured Image: View of the Confederate memorial, with an added Confederate flag made out of flowers, Jasper, Alabama, 2010. (Carol M. Highsmith/Buyenlarge/Getty Images)