By: Micah Smith, The Denver Channel —

DENVER — Throughout Denver, there’s a growing racial justice movement focused on reparations and reconciliation. Most of those involved in this push to bridge the racial divide have been encouraged to do so after discovering a dark part of their family history.

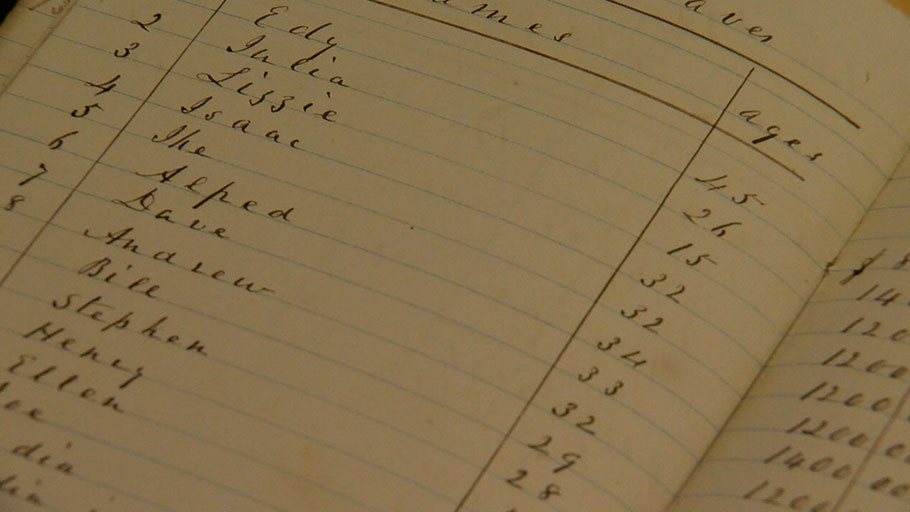

While going through some old family records, retired financial strategist Lotte Lieb Dula discovered her great-great grandfather’s leather-bound notebook that held a family secret.

“This is a ledger book with a list of the slaves here,” she said. “My family enslaved hundreds of people. So far, I found over 400 slaves and I’m thinking it’s be in the thousands when I complete my research.”

Dula discovered even more family secrets.

“My sister and I were dividing up my grandmother’s things,” she said. “I chose a ring because it says ‘to thine own self be true’ on the inside… I actually wore this ring for a month until I thought I’d better see what the signet represents. Well it’s a fraternal order that was founded in 1865. Later, I discovered was that my grandmother was a member of the KKK club at Smith College.”

Restorative Justice Advocate Harold Fields said Dula’s discovery has major implications beyond just her family.

“Just like wealth can be inherited, poverty can be inherited and passed on if you don’t have the ability to help the next generation,” Fields said. “So, there’s tough work of trying to bridge this gap.”

Hoping to bridge that gap, Dula found Fields and others working toward racial reconciliation through an organization called Coming to the Table.

“The goal is that the descendants of enslavers or slave traders… meet with (and) join with the descendants of the enslaved to heal the racial divide and to, honestly, to eradicate institutional racism,” said Dula. “Denver now has a Coming to the Table group and we get together and do readings and discuss what to do in our community.”

After confronting her painful family history and consulting with members of the group, Dula started her own website, Reparations4Slavery.com to help others with similar stories.

“Most people have no idea what to do when they make this kind of discovery so I kind of created a little path for them to follow with some things that are easy to do and some things that are more difficult,” Dula said.

She didn’t put away the family slave ledger that launched her truth-seeking journey. Instead, she’s sharing it with black and white people looking for their own truth.

“You know, for many of us, our history has just been cut off. Records are not there,” Fields said.

Dula said if people have documents like she does, it’s important to repatriate them so other people can find their ancestors.

“For instance, I’ve already been contacted by one person who has seen the listing of the enslaved and thinks that it’s possible that they may be a descendant,” she said.

Like her family’s plantation home in Virginia, Dula’s family wealth still survives.

“What my family owes African Americans — there is no way to quantify that,” she said. “The only thing I can do is — I’m dedicating my life to do what I can to repair this damage. I feel it’s my responsibility to make reparations.”

At a national gathering of Coming to the Table, Dula met Briayna Cuffie and began the reparations process.

“With Lotte, we had spoken pretty much throughout the entire weekend,” Cuffie said. “She told me about the reparations project she was working on… Lotte also mentioned that she would love to assist in putting money toward my student loans and it just kind of blew my mind.”

Dula’s reparations are helping Cuffie pay off her student loans and continue with her career path focused on justice and politics.

But for Cuffie, reparations aren’t just about money.

“I think getting people involved in politics and helping them through their own personal journeys as well, — I would say is almost just as beneficial,” said Cuffie.

Holly Fulton, another active member of Coming to the Table said reparations to her means speaking the truth and going public with her own family history.

“I’m sort of shifting or expanding my vision of what reparations encompasses,” Fulton said.

She was a part of a small group of the large DeWolf family that created a documentary about their slave trading ancestors.

Fulton commissioned a painting by artist Kolongi to document her emotional journey.

“They have been called, many times, the biggest family slave-trading business in the history of the United States,” she said.

But by sharing her family’s slave trading history with others, some of Fulton’s own siblings became angry, preferring to keep family secrets hidden in the dark.

“I think it’s an automatic reaction that a lot of people have is zip it up, don’t talk about it,” she said. “So, I’m rocking the boat in talking about this.”

Fulton said she no longer feels guilty about her ancestors’ actions but she does feel a sense of responsibility to begin efforts to repair some of the harm her ancestors caused.

“I don’t want to get on my high horse and say I’ve done all of the work,” she said. “No, I think I’m going to be continuing this work until I die.”

To Cuffie, Fulton, and Dula, reparations means something different:

For Cuffie it’s ending financial inequalities caused by racial injustice. For Fulton, reparations means speaking truth to black Americans’ pain. And for Dula, it’s using her resources to help break the lingering societal chains her ancestors first placed on African Americans all those years ago.