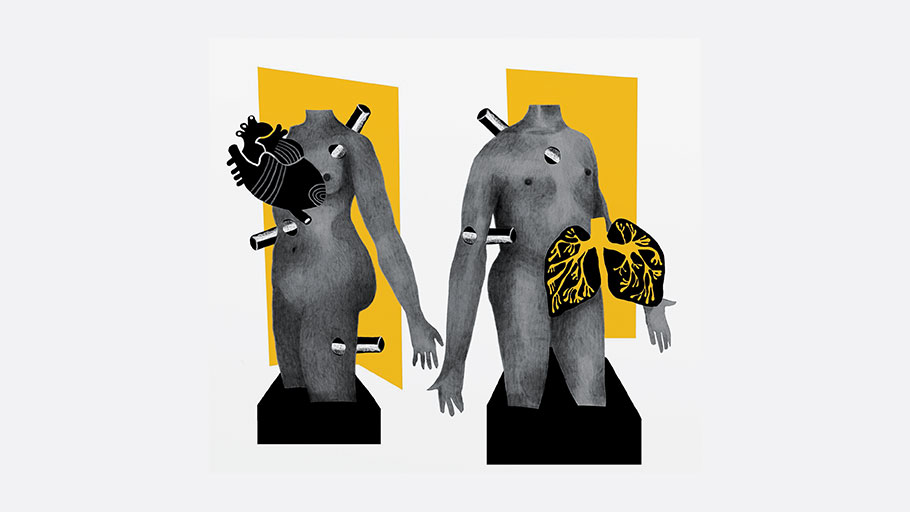

Myths about physical racial differences were used to justify slavery — and are still believed by doctors today.

By Linda Villarosa, New York Times —

The excruciatingly painful medical experiments went on until his body was disfigured by a network of scars. John Brown, an enslaved man on a Baldwin County, Ga., plantation in the 1820s and ’30s, was lent to a physician, Dr. Thomas Hamilton, who was obsessed with proving that physiological differences between black and white people existed. Hamilton used Brown to try to determine how deep black skin went, believing it was thicker than white skin. Brown, who eventually escaped to England, recorded his experiences in an autobiography, published in 1855 as “Slave Life in Georgia: A Narrative of the Life, Sufferings, and Escape of John Brown, a Fugitive Slave, Now in England.” In Brown’s words, Hamilton applied “blisters to my hands, legs and feet, which bear the scars to this day. He continued until he drew up the dark skin from between the upper and the under one. He used to blister me at intervals of about two weeks.” This went on for nine months, Brown wrote, until “the Doctor’s experiments had so reduced me that I was useless in the field.”

John Brown, who escaped slavery and published an autobiography about his experiences, after he arrived in England. From the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture.

Hamilton was a courtly Southern gentleman, a respected physician and a trustee of the Medical Academy of Georgia. And like many other doctors of the era in the South, he was also a wealthy plantation owner who tried to use science to prove that differences between black people and white people went beyond culture and were more than skin deep, insisting that black bodies were composed and functioned differently than white bodies. They believed that black people had large sex organs and small skulls — which translated to promiscuity and a lack of intelligence — and higher tolerance for heat, as well as immunity to some illnesses and susceptibility to others. These fallacies, presented as fact and legitimized in medical journals, bolstered society’s view that enslaved people were fit for little outside forced labor and provided support for racist ideology and discriminatory public policies.

Over the centuries, the two most persistent physiological myths — that black people were impervious to pain and had weak lungs that could be strengthened through hard work — wormed their way into scientific consensus, and they remain rooted in modern-day medical education and practice. In the 1787 manual “A Treatise on Tropical Diseases; and on The Climate of the West-Indies,” a British doctor, Benjamin Moseley, claimed that black people could bear surgical operations much more than white people, noting that “what would be the cause of insupportable pain to a white man, a Negro would almost disregard.” To drive home his point, he added, “I have amputated the legs of many Negroes who have held the upper part of the limb themselves.”

These misconceptions about pain tolerance, seized upon by pro-slavery advocates, also allowed the physician J. Marion Sims — long celebrated as the father of modern gynecology — to use black women as subjects in experiments that would be unconscionable today, practicing painful operations (at a time before anesthesia was in use) on enslaved women in Montgomery, Ala., between 1845 and 1849. In his autobiography, “The Story of My Life,” Sims described the agony the women suffered as he cut their genitals again and again in an attempt to perfect a surgical technique to repair vesico-vaginal fistula, which can be an extreme complication of childbirth.

Thomas Jefferson, in “Notes on the State of Virginia,” published around the same time as Moseley’s treatise, listed what he proposed were “the real distinctions which nature has made,” including a lack of lung capacity. In the years that followed, physicians and scientists embraced Jefferson’s unproven theories, none more aggressively than Samuel Cartwright, a physician and professor of “diseases of the Negro” at the University of Louisiana, now Tulane University. His widely circulated paper, “Report on the Diseases and Physical Peculiarities of the Negro Race,” published in the May 1851 issue of The New Orleans Medical and Surgical Journal, cataloged supposed physical differences between whites and blacks, including the claim that black people had lower lung capacity. Cartwright, conveniently, saw forced labor as a way to “vitalize” the blood and correct the problem. Most outrageous, Cartwright maintained that enslaved people were prone to a “disease of the mind” called drapetomania, which caused them to run away from their enslavers. Willfully ignoring the inhumane conditions that drove desperate men and women to attempt escape, he insisted, without irony, that enslaved people contracted this ailment when their enslavers treated them as equals, and he prescribed “whipping the devil out of them” as a preventive measure.

Today Cartwright’s 1851 paper reads like satire, Hamilton’s supposedly scientific experiments appear simply sadistic and, last year, a statue commemorating Sims in New York’s Central Park was removed after prolonged protest that included women wearing blood-splattered gowns in memory of Anarcha, Betsey, Lucy and the other enslaved women he brutalized. And yet, more than 150 years after the end of slavery, fallacies of black immunity to pain and weakened lung function continue to show up in modern-day medical education and philosophy.

Even Cartwright’s footprint remains embedded in current medical practice. To validate his theory about lung inferiority in African-Americans, he became one of the first doctors in the United States to measure pulmonary function with an instrument called a spirometer. Using a device he designed himself, Cartwright calculated that “the deficiency in the Negro may be safely estimated at 20 percent.” Today most commercially available spirometers, used around the world to diagnose and monitor respiratory illness, have a “race correction” built into the software, which controls for the assumption that blacks have less lung capacity than whites. In her 2014 book, “Breathing Race Into the Machine: The Surprising Career of the Spirometer from Plantation to Genetics,” Lundy Braun, a Brown University professor of medical science and Africana studies, notes that “race correction” is still taught to medical students and described in textbooks as scientific fact and standard practice.

A 19th-century spirometer, used to measure the vital capacity of the lungs. Getty Images.

Recent data also shows that present-day doctors fail to sufficiently treat the pain of black adults and children for many medical issues. A 2013 review of studies examining racial disparities in pain management published in The American Medical Association Journal of Ethics found that black and Hispanic people — from children with appendicitis to elders in hospice care — received inadequate pain management compared with white counterparts.

A 2016 survey of 222 white medical students and residents published in The Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences showed that half of them endorsed at least one myth about physiological differences between black people and white people, including that black people’s nerve endings are less sensitive than white people’s. When asked to imagine how much pain white or black patients experienced in hypothetical situations, the medical students and residents insisted that black people felt less pain. This made the providers less likely to recommend appropriate treatment. A majority of these doctors to be also still believed the lie that Thomas Hamilton tortured John Brown to prove nearly two centuries ago: that black skin is thicker than white skin.

This disconnect allows scientists, doctors and other medical providers — and those training to fill their positions in the future — to ignore their own complicity in health care inequality and gloss over the internalized racism and both conscious and unconscious bias that drive them to go against their very oath to do no harm.

The centuries-old belief in racial differences in physiology has continued to mask the brutal effects of discrimination and structural inequities, instead placing blame on individuals and their communities for statistically poor health outcomes. Rather than conceptualizing race as a risk factor that predicts disease or disability because of a fixed susceptibility conceived on shaky grounds centuries ago, we would do better to understand race as a proxy for bias, disadvantage and ill treatment. The poor health outcomes of black people, the targets of discrimination over hundreds of years and numerous generations, may be a harbinger for the future health of an increasingly diverse and unequal America.

This article was originally published by the New York Times as a part of the 1619 Project. The 1619 Project is a major initiative from The New York Times observing the 400th anniversary of the beginning of American slavery. It aims to reframe the country’s history, understanding 1619 as our true founding, and placing the consequences of slavery and the contributions of black Americans at the very center of the story we tell ourselves about who we are. Read all the stories.

Linda Villarosa directs the journalism program at the City College of New York and is a contributing writer for the magazine. Her feature on black infant and maternal mortality was a finalist for a National Magazine Award.

Featured image: Illustration by Diana Ejaita