Formerly enslaved people preparing cotton for the gin on Smith’s plantation, Port Royal Island, South Carolina, 1861–1862 — Timothy H. O’Sullivan/Library of Congress

By Katherine Franke —

A bill calling for the federal government to “study and consider” how to provide reparations to African Americans for slavery has been introduced into every session of the US Congress for the last thirty years. The bill’s aim is “to address the fundamental injustice, cruelty, brutality, and inhumanity of slavery in the United States and the thirteen American colonies between 1619 and 1865.” Representative John Conyers, the primary sponsor of the bill, stated in 2017 just before he retired from the Congress, “I’m not giving up… Slavery is a blemish on this nation’s history, and until it is formally addressed, our country’s story will remain marked by this blight.” Through both Democratic and Republican control of the House, the bill only once got a hearing (in 2007)—but may again this year, since House Speaker Nancy Pelosi voiced support for the proposal.

Most recently, three Democratic presidential candidates—Kamala Harris, Elizabeth Warren, and Julián Castro—endorsed the concept of granting reparations to black Americans affected by slavery and racial discrimination.(By contrast, Senator Bernie Sanders decried the call for reparations as “divisive.”) David Brooks recently made the case for reparations on the editorial page of The New York Times, and Ta-Nehisi Coates’s foundational essay on reparations from 2014 in The Atlantic has received renewed interest. It seems that the time for meaningful consideration of reparations for slavery may have finally arrived—154 years after the institution of slavery was formally abolished in the United States.

The ripening of this realization has emerged as a response to the intractability of African Americans’ second-class political status in the US and the undeniable historical roots of black poverty, including recent data from the Federal Reserve’s Survey of Consumer Finances showing that the typical black family has only 10 cents for every dollar of wealth held by the typical white family. There is a ready and workable model of how to repair the intergenerational disadvantage suffered by black people in the US: in communities across the country, racial justice activists have developed creative legal measures to move control and ownership of land into black communities. A collective, land-based approach to reparations makes particular sense as a remedy to redress the dire injustice suffered by humans who were treated as property.

Today’s emerging embrace of the moral imperative of granting reparations for slavery to black people renews an unanswered call that dates back to the end of the Civil War. There was then a widely accepted notion that delivering justice to formerly enslaved people must entail something more than emancipation alone. Contemporary calls for reparations are premised on the notion that the past has enduring moral and material relevance today, that slavery, though outlawed, has an enduring afterlife, that this afterlife pervades American culture, and that we should face, know, and make amends for that past.

In fact, Union military and political leaders who were directly responsible for stewarding black people from enslavement into their new lives as freed people felt strongly that slavery was an atrocity and a theft that required compensation. Reparations were understood as both a remedy for the rape, torture, death, and destruction of millions of human souls, and a measure that recognized that freedom without material resources would lock black people into second-class status for generations to come. And so it did.

Land-based reparations were thus promised at the end of the Civil War, with ambitious programs undertaken in several significant communities in the South. In the Sea Islands off South Carolina, and on the plantations owned by the slaveholders Jefferson Davis and his brother Joseph, just outside of Vicksburg, Mississippi, radical experiments in land redistribution to formerly enslaved people were undertaken explicitly as a form of reparation for slavery.

Indeed, the process of redistributive justice began well before the war was over, as early as 1861. On November 3 of that year, the largest attack fleet ever to sail under the US flag was amassed to capture Port Royal, South Carolina. Confederate white Islanders were clearly outgunned and outmanned, and three days later, nearly all of the local white men had packed their wives, children, and favorite “servants” (the innocuous term many slaveholders used for the people they enslaved) into boats and rowed to the mainland. Here, as elsewhere in the South, federal troops immediately emancipated the black people held in bondage in territory under northern military control. So, when federal troops assumed control of the Sea Islands, approximately 10,000 black people living on 189 plantations were immediately set free, more than a year before President Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation.

Corbis via Getty Images

Five months later, in early 1862, Brigadier General Rufus Saxton assumed governorship of the Sea Islands of South Carolina. It quickly became clear to him that something more was owed the black people of the Sea Islands than emancipation into abject poverty. The Union general viewed the freed people as holding an equitable mortgage on the land, secured by their past unpaid wages, sweat, blood, and lost lives. According to Saxton:

They had been the only cultivators, their labor had given it all its value, the elements of its fertility were the sweat & blood of the negro so long poured out upon it, that it might be taken as composed of his own substance. The whole of it was under a foreclosed mortgage for generations of unpaid wages.

A teacher from Philadelphia who traveled to the Sea Islands to help educate freed people echoed Saxton’s argument: “If there is any class of people in the country who have priority of claim to the confiscated lands of the South, it certainly is that class who have by years of suffering and unrequited toil given to those lands any value they may now possess.” This plea to make land ownership a key component of freedom for black people is all the more compelling given that many slave-owners used slaves as collateral in order to purchase land in the ante-bellum period.

Thus began a huge project of allocating to freed people land that had been confiscated by the federal government from Confederate plantation owners who fled the Sea Islands and abandoned their property. The enterprise of providing such reparations in the form of land titles became official policy when, in January 1865, Union General William Tecumseh Sherman issued Special Field Order No. 15, confiscating a strip of coastline stretching from Charleston, South Carolina to the St. John’s River in Florida, and into the mainland thirty miles from the coast. The order redistributed the roughly 400,000 acres of land to newly freed black families in forty-acre lots. On this land, Sherman ordered, “no white person whatever, unless military officers and soldiers detailed for duty, will be permitted to reside,” and the freed people would be left to their own control.

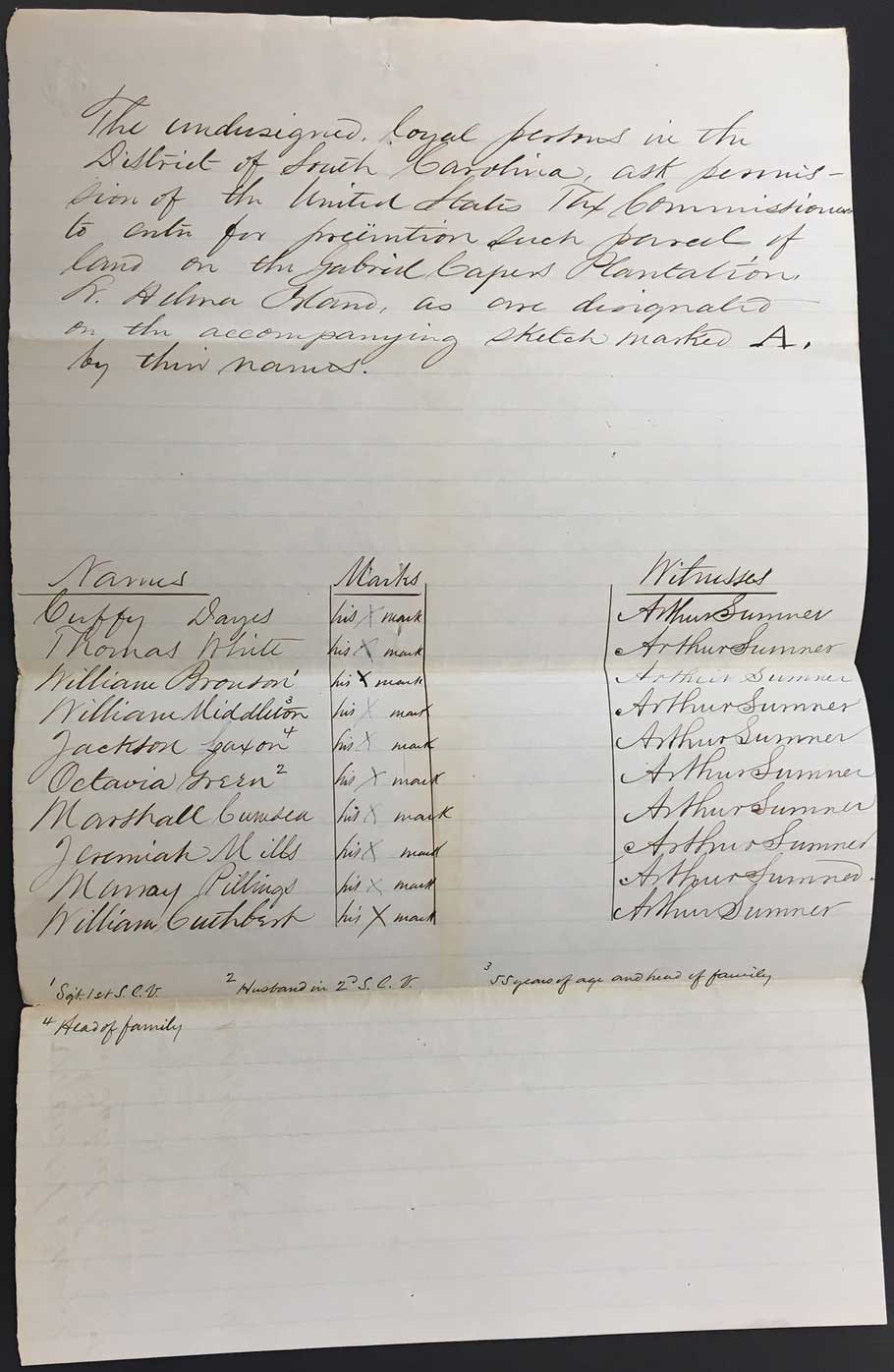

Four months later, Confederate General Robert E. Lee surrendered to General Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox. The daunting project of repairing the wounds of slavery through the issuance of “Sherman land titles” to newly freed black people continued, as did auctions of confiscated land in which freed people were able to purchase the land on which they had been enslaved, often collectively with pooled resources. These original land titles are housed in the National Archives, and when I viewed them last year, I was moved to see the Xs where freed people signed applications for land on which they and their people had, not long before, been enslaved. Next to the “X” for many freed people’s signatures are ink smudges seeming to bear witness to the trembling hands undertaking this remarkable act of freedom.

For instance, on January 29, 1864, ten formerly enslaved men and women filed a claim collectively for what had been the Gabriel Capers plantation:

Land Claim for the Gabriel Capers Plantation from records of the Internal Revenue Service (Record Group 58), January 29, 1864 — Katherine Franke/The National Archives and Records Administration

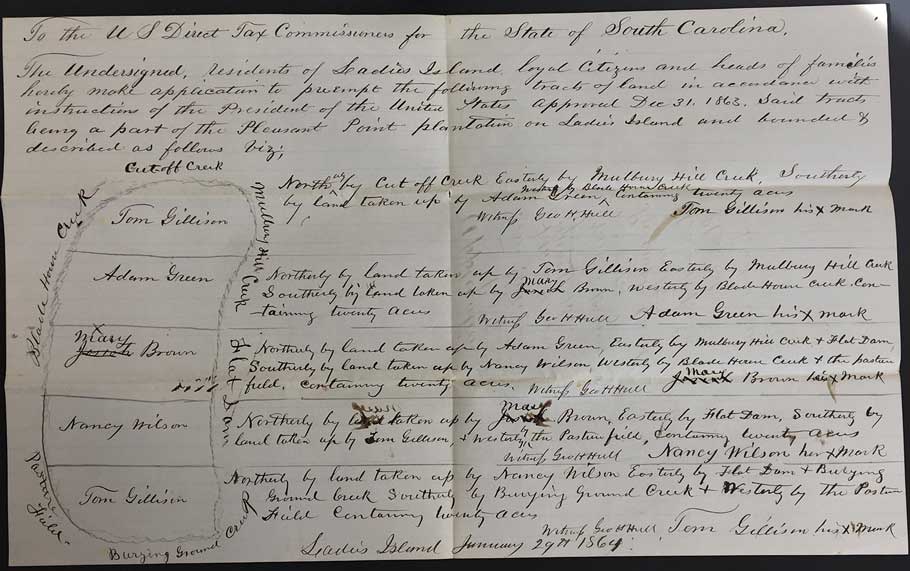

Another group of freed people filed a claim for the Pleasant Point plantation, accompanied by a hand-drawn map indicating how they would share the parcels as a community:

Land Claim for the Pleasant Point Plantation from records of the Internal Revenue Service (Record Group 58), January 29, 1864 — Katherine Franke/The National Archives and Records Administration

At the land auctions, formerly enslaved people also acquired implements and farm animals needed to work the land. It was reported that three black men bought a horse at auction and then, thumbing their noses at their former owners, named it “massa”!

This historic enterprise of reparative justice came to an abrupt end after President Lincoln was assassinated and Andrew Johnson, a known slavery sympathizer, assumed the presidency of the United States. Johnson vetoed a bill Congress sent to his desk that would have formalized the allocation of land to newly freed black people as reparations, and he granted amnesty to the former Southern Confederate landowners by signing an “Iron Clad Oath” that restored “all rights of property, except as to slaves.”

In this way, the land that had been set aside and granted to freed people to begin a new life was seized from them, often violently, and returned to their former owners, even though, in many cases, they had paid for title to the land at public auction. Freed people were then forced to enter into contract labor arrangements with plantation owners that bore a greater resemblance to slave labor than to freedom. Without land or other resources, newly freed people were rendered completely vulnerable to the whims and interests of the very white people who regarded them more as property to be used and exploited than as people who bore rights and dignity.

The disestablishment of the institution of slavery released millions of people from bondage, but it did little to redress the horror of slavery itself. That horror stretched backward to include the loss of dignity, forced labor, family separation, sexual exploitation, human commodification, and the sheer sadism enslavement entailed, and reached forward to mark black people as inferior, relegating them to a second-rate form of freedom. What enslaved people got when they were emancipated was freedom on the cheap. The dangling “d” at the end of “free” stood for the residue of enslavement that bound them to a past, marking their future as freed, not free, people. It reinforced a racial hierarchy in which freedom for the formerly enslaved meant something different, and worse, than it did for white people as a matter of natural, or God’s, law.

It is both the promise and the failure of reparation in the 1860s that should animate a return to reparations now, not in the form of individual cash grants but through collective resource redistribution. Structural, comprehensive, and enduring reparation is required to address the wounds of the past and to ameliorate the entrenched social, political, economic, and legal status of freed people as something less than white people.

Unfortunately, what might have been the right thing to do in 1865 would be impossible or unwise to do now. Even though freed people were entitled to land in 1865, it is inconceivable to imagine a scenario today in which the land set aside by General Sherman’s Special Field Order No. 15 would be confiscated from its current owners—black, white, and others—and allotted to the descendants of US slaves.

The vexing questions of who should pay for, and who should be the recipients of reparations for slavery often get stuck in the cul-de-sac of debates about intergenerational responsibility, intervening causation, exculpatory pleading of white innocence, and complex actuarial calculations. Rather than focusing the discussion on individual culpability or desert, our history justifies a more collective moral reckoning with the lasting manifestations of slavery. White speculators from Boston, New York, Philadelphia, and Pittsburgh capitalized as much or more on the return of the “Sherman land titles”to white people than did former Confederate plantation owners. And the racist policies that tainted black “freed-dom” and citizenship with a badge of inferiority did not attach only to people who had been enslaved—it adhered to black identity itself.

In this respect, the enslavement of black people, which was a consequence of the overarching ideology of white supremacy, was integral to America’s national story and development as a nation. White supremacy metastasized from the original laws and customs that supported the enslavement of black people into so-called Black Codes that secured their subordinate status after slavery was formally abolished by the Thirteenth Amendment, and in the succession of Jim Crow laws that secured a separate and unequal status for African Americans on the books and in practice. This entire legacy continues to structure the US economy and political system to this day.

The failure to deliver real economic justice to formerly enslaved people relegated black people to the status of permanent subaltern citizens, kept down by a range of government policies and practices. At the same time, through numerous public programs (beginning as far back as 1785), the US government gave land to white people in order to facilitate wealth accumulation for the nation and for its white citizens. Real estate investment has been the greatest wealth-generating machine in our nation’s history, yet African Americans have been systematically locked out of the opportunity to buy in, sit tight, and get rich. The GI Bill underwrote segregated housing through discriminatory lending policies. For decades, realtors steered black buyers to black neighborhoods and whites to white neighborhoods, while local and federal governments invested in the infrastructure in white neighborhoods but systematically underinvested in black neighborhoods.

As a result, white people have been given opportunities to profit from booming real estate markets that excluded African Americans. Promises made to freed people in 1865 that they would receive land—as reparations for their enslavement and the leg-up they needed to start their lives anew—were never honored.

The broken promise of reparations goes a long way toward explaining why, in 2013, the median wealth of white households was thirteen times greater than for black households (the largest gap in a quarter-century), and why, in 2011, 73 percent of white households owned their homes, in contrast to only 45 percent of African American households doing so. Structural barriers persist today that make it impossible for black people ever to catch up financially, no matter how hard they work; white people have a 150 years’ head start on wealth accumulation.

As Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. put it during his 1968 “Poor People’s Campaign” tour through Mississippi:

At the very same time that America refused to give the Negro any land, through an act of Congress our government was giving away millions of acres of land in the West and the Midwest, which meant it was willing to undergird its white peasants from Europe with an economic floor… We are coming to get our check.

Rather than writing checks to individuals, collective remedies may better address the historical need for structural repair. We can look to innovative models, such as reinvestment in black communities through community land trusts, limited-equity housing cooperatives, zero-equity co-operatives, mutual housing associations, and deed-restricted housing—sometimes referred to as “third-sector housing”—all used to empower black communities by transferring resources and property into those communities. These measures remove land, and especially housing, from the speculative, for-profit real estate market and place it into the hands, and under the control, of black communities, thus reproducing in modern form the Sherman land grants of the 1860s.

How can we pay for this kind of collective repair? I favor taxing the intergenerational transfer of wealth from the “greatest generation” to middle-aged “baby boomers.” The lucky ones of my generation who stand to benefit from a lottery-like windfall should feel obliged by history’s burden to disgorge a part of what is truly an unjust enrichment, made possible by the failure of political will in the nineteenth century to deliver meaningful justice to millions of people when slavery was abolished.

Today’s presidential candidates and members of Congress who endorse reparations for slavery are hoping to make good on the unrealized promise of true freedom for the millions of people who endured rape, torture, death, and destruction through the institution of chattel slavery. To ignore the moral imperative of repairing the wounds of slavery because doing so might be “divisive” reinforces an exculpatory myth of white innocence in our nation’s history. Black lives will continue to be treated as though they do not matter until we take material steps to repair the intergenerational wreckage that slavery continues to inflict.

This article was originally published in The New York Review of Books