Democratic presidential candidate Marianne Williamson speaks during the second night of the first Democratic presidential debate. Photo: Al Diaz, Miami Herald

Most Americans overwhelmingly oppose reparations to African Americans descendants of enslaved persons. But a slight uptick in support especially among younger Americans in recent years may be a result of activism over police killings over past five years.

By Valerie Russ, The Philadelphia Inquirer —

Only one of the Democratic candidates for the 2020 presidency brought up reparations at the political debates last week.

It was Marianne Williamson, a best-selling author, self-help guru and spiritual adviser to Oprah Winfrey, considered on the fringe among the crowded field of candidates. In other words, a long shot.

Could it be the same for the idea of reparations?

Despite recent attention to reconsider House Resolution 40, a bill that aims to establish a commission to study the subject, the most recent polls show an overwhelming majority of Americans, especially white Americans, still oppose reparations to African American descendants of enslaved people.

But that number is decreasing.

An April 2019 survey of 1,000 likely voters by the Rasmussen Report found that 21 percent — up from 17 percent in March 2018 — think U.S. taxpayers should pay reparations to black Americans “who can prove they are descended from slaves.” Another 66 percent oppose reparations — down from 70 percent — while 13 percent are undecided. (Gallup is currently conducting its own survey on reparations, a spokesperson said.)

The Rasmussen Report, as other polls have shown in recent years, highlights a sharp division based on race.

The April 2019 survey shows that 60 percent of black Americans favor reparations, while only 12 percent of whites favor it. And 73 percent of whites, 32 percent of blacks, and 64 percent of other minority voters are opposed to it.

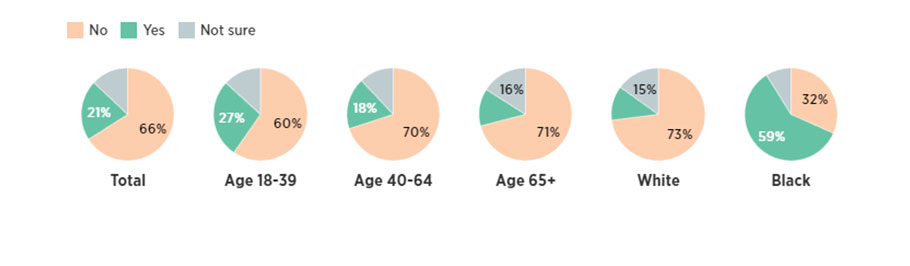

Attitudes Toward Reparations

A poll from April of 1,000 likely U.S. voters showed about one in five supported reparations for black Americans, with wide differences based on the age and race of the respondents. Question: Should U.S. taxpayers pay reparations to black Americans who can prove they are descended from slaves?

Attitudes Toward Reparations Poll – Question: Should U.S. taxpayers pay reparations to black Americans who can prove they are descended from slaves? Chart: John Duchneskie, Staff Artist. Source: Rasmussen Reports

In 2016, a Marist Poll found that overall, 68 percent of all Americans oppose reparations, with 81 percent of whites and 35 percent of black Americans opposing. For Hispanics, it was almost an even split, with 47 percent against and 46 percent supporting.

However, the numbers change among younger generations.

For Gen Xers — ages 35 to 50 — 25 percent supported reparations. For millennials — ages 18 to 34 — 40 percent were in favor of reparations.

William Darity Jr., an economics professor at Duke who has researched the racial wealth gap and reparations for decades, said he sees the ever-so-slight increase in support as notable.

“There was a survey taken in 2000 which indicated that four percent of white Americans endorsed reparations,” he said. “There are so many things in society that, at some point, the majority opposed what was the right thing to do — for example, the abolition of slavery.”

Ana Lucia Araujo, a history professor at Howard University and author of the book Reparations for Slavery and the Slave Trade, said the growing support for reparations may be tied to the activism that followed highly publicized killings of black people by police: Michael Brown, Eric Garner and Tamir Rice in 2014; Sandra Bland in 2015; and Philando Castile in 2016.

In August 2016, Araujo said, the Movement for Black Lives developed a platform to fight police violence:

“Government, responsible corporations, and other institutions that have profited off of the harm they have inflicted on Black people — from colonialism to slavery through food and housing redlining, mass incarceration, and surveillance — must repair the harm done.”

Additional signs of increasing support: the recent decision by Georgetown University students to pay $27.20 a semester that would support a reparations fund to the descendants of the 272 enslaved men, women, and children who were sold by Jesuits to finance the university.

An April 2019 Vox article, “The Great Awokening,” noted big change in the past five years, since protests in Ferguson, Mo., after Michael Brown was killed.

“White liberals have moved so far to the left on questions of race and racism that they are now, on these issues, to the left of even the typical black voter.” This “awokeness,” the article suggests, has begun to shift public opinions on race:

“The leftward shifts on immigration, criminal justice, and reparations are often described as reflecting the electoral clout of nonwhite voters. … The key difference is that white liberals have changed their minds very rapidly, thus altering the political space in which Democratic Party politicians operate.”

While they didn’t mention reparations during the debates, a handful of Democratic candidates — Sens. Cory Booker, Elizabeth Warren, and Kamala Harris, and former Housing and Urban Development Secretary Julián Castro — have all said at some point that they would consider reparations in some form.

But some black conservatives have strongly condemned the notion of reparations.

“It’s a sham,” said Horace Cooper, a lawyer and co-chair of Project 21 National Advisory Board of the National Center for Public Policy Research.

He said the push for reparations would only continue to divide Americans along racial lines. Cooper instead called on black Americans to focus on encouraging strong, intact families and advocating for higher education, especially in math and sciences, for their children.

“We believe in the brilliance and capability in the black community,” Cooper said. “If we continue to focus on what someone else did to us, we’re going to miss out on what we are actually capable of doing.”

Darity, the Duke economist, said he was once skeptical about reparations. He is co-author of From Here to Equality: Reparations for Black Americans in the 21st Century, a book scheduled to be published next year.

“Not because I thought it was wrong in principle, but at the time, I didn’t think it was realistic,” Darity said. “I reached the conclusion that if it’s the right thing to do, then you struggle for it even if the odds are long.”