This is Part 1 of a 4 part series on Reparations by Yes!

“If you fail to pay us for faithful labors in the past, we can have little faith in your promises in the future. We trust the good Maker has opened your eyes to the wrongs which you and your fathers have done to me and my fathers, in making us toil for you for generations without recompense.” — letter to former master from Jourdon Anderson

A peace treaty is a document that spells out how warring parties can cease violence. Often there is systemic change that follows at every level, from the federal government to local institutions. After WWII, the U.S. required Germany and Japan to change their constitutions, demilitarize, and educate their citizenry for peace in order to prevent other wars.

Inside U.S. borders, there have been numerous treaties with the Indigenous peoples of this land—many of them broken. This nation has even issued reparations as a peace treaty in recent history to Japanese Americans who were forced into internment camps. That treaty, known as the Civil Liberties Act of 1988, just marked its 30th anniversary last year.

Until recently, serious discussions of reparations for the enslavement of African peoples on this land and the subsequent oppression of their descendants—through Jim Crow, Black Codes, redlining, mass incarceration, and deadly racist policing—have fallen on deaf ears among most U.S. lawmakers, and those outside of the scattered silos of African American activists. It represents a remarkable turn of events that on Juneteenth of this year—a previously under-recognized yet historically significant day—Congress held a hearing on reparations.

Now, extraordinarily, people at various points along the political spectrum have signaled some level of support for reparations. History tells us that when such a political consensus emerges on both sides of the aisle, we may be moving toward a cultural and political tipping point.

Therefore, we should take advantage of this moment by considering all that reparations entails. The United Nations defines reparations as involving:

1. Restitution, or return of what was stolen;

2. Rehabilitation, in the form of psychological and physical support. Consider how the maternal health of Black mothers and the trauma inflicted on Black bodies impacts our daily experience in the White world. But rehabilitation is also for White folks—because it encourages healing from Whiteness, which is an existential or spiritual problem, as it posits White as superior;

3. Compensation, which must incorporate meaningful transfer of wealth. While some of us just want a check, reparations can’t only be transactional, because those most likely facilitating the transaction—large banks—continue to play an active role in keeping our communities disenfranchised through redlining, predatory lending, and so much more;

4. Reconciliation, which requires acknowledgement of guilt, apology, burials, construction of memorials, and education about the true history of this nation’s founding sin;

5. Guarantees of non-repetition, which reinforces reparations as a long-term process that requires systemic and personal change.

The slate of Democratic presidential candidates has, so far offered a limited vision of reparations, given their need to present palatable sound bites digestible for mainstream media. And overall most people—including politicians—are not yet thinking of reparations as an instrument for peace.

We recognize the militarization of law enforcement as the manifestation of a war waged against Black communities.

My colleague Tarell Kyles, a Ph.D. candidate at Pacifica Graduate Institute, told me during a recent conversation about decolonization, “Reparations is a peace treaty.”

His statement was brought on by the scholarship of Maldonado Torres, who points out the state of being colonized is never separate from ideas of war. When we think of the ways in which “wars” on drugs and poverty were wars on people, it is easier to see the connection between reparations and peace: from urban renewal programs that were actually urban removal programs—displacing people of color from their neighborhoods—to redlining that kept Black people from building wealth, from the G.I. Bill’s exclusion of Black veterans from opportunities to the weaponization of the Fair Housing Act to gentrify Black and Brown communities.

From this lens of direct structural violence, Torres explains that violence against Black, Indigenous, and people of color (BIPOC) has been normalized in ways the status quo—and sometimes our own communities—doesn’t see as an actual war.

But from Ferguson to Baltimore, we recognize that the militarization of law enforcement—with its tanks, tear gas, and military gear—is the manifestation of a war waged against Black communities.

If we ever needed an intervention, we need it now. Black people continue to be killed without consequence. The killers of Eric Garner, Sandra Bland, Antwon Rose, or the countless others whose names we do not know will never be held accountable.

In the next five parts of this series, we will explore what a Reparations Peace Treaty would look like: national educational initiatives teaching young citizens about the true history of this nation; educating for peace rather than war; an abolishing of prisons and police; and a complete end to war.

Cases for reparations have already been made. Reparations are a long overdue debt, and it is beyond time to collect. The question is no longer whether reparations are owed or should be paid, but a matter of when and how.

As we begin our journey toward this process, the FOR Truth and Reparations campaign, #ReparationSundays, has created two national days of reparations observance for spiritual and faith communities to help people unravel themselves from White supremacy. Many spiritual and faith communities have taken up the work of addressing racism and reparations. As Rev. angel Kyodo williams, a Buddhist priest and co-author of Radical Dharma: Talking Race, Love, and Liberation, posits, “The conversation about reparations is about personal reckoning.” Rabbi Ruth Zlotnick in Seattle calls us to atone for slavery. These positions will be further explored in this series.

This series will demonstrate that reparations are not only a political and social intervention in the lives of Americans, but also a spiritual one that opens the possibility for reconciliation in the pursuit of justice and true peace.

This article originally published by Yes! and republished under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 license.

Read More:

- Reparations Are a Peace Treaty

- With Reparations, We Must Demand Repair—and Heal Ourselves

- On Reparations, Let Impacted Communities Lead the Way

- Beyond Compensation for Reparations

David Ragland is the Senior Bayard Rustin Fellow at the Fellowship of Reconciliation (FOR USA). David is the director of the campaign FOR Truth and Reparations, and co-founder of the Truth Telling Project of Ferguson, which began in the early days of the Ferguson Uprising to shift the narrative of the protests and police violence. David is also a member of the Stony Point Community of Living Traditions and the Muslim Peace Fellowship in Stony Point, New York.

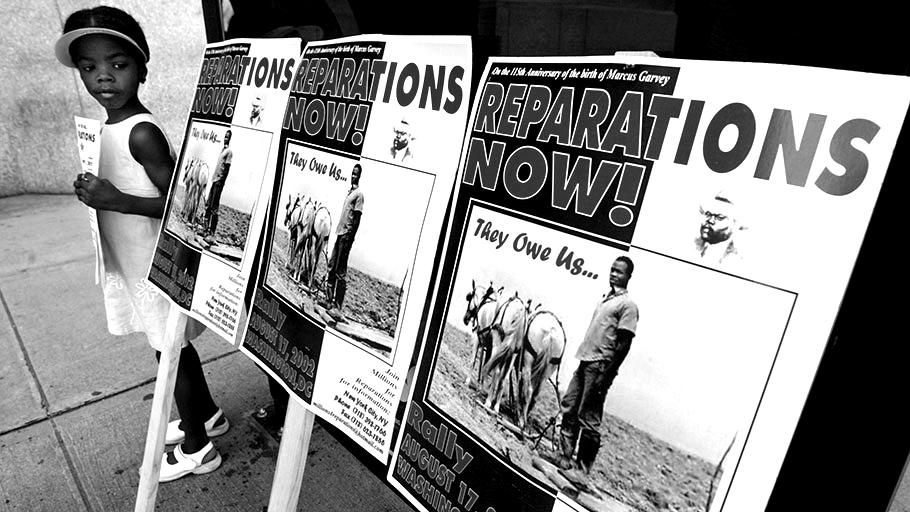

Featured Image: Lindi Bobb, 6, attends a slavery reparations protest on August 9, 2002 in New York City. On June 19, 2019, the House Judiciary Committee held hearings on legislation proposing the establishment of a commission to study reparations. Mario Tama/Getty Images