Tulsa was the scene of a violent attack on a thriving African American community nearly a century ago

During World War I (1914-1918) and the immediately following years (1919-1921), racial tensions escalated inside the United States resulting in numerous efforts by white racists to contain and in many cases remove the presence of African Americans.

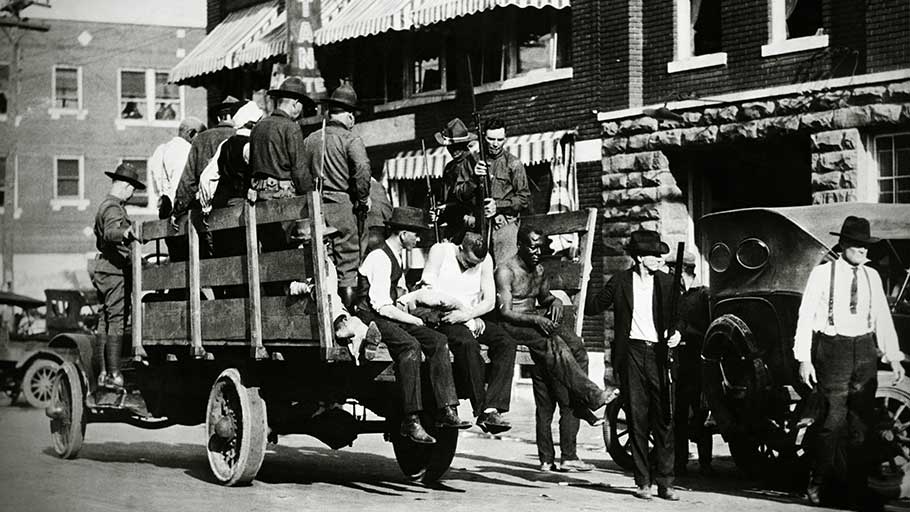

One of the most violent disturbances occurred in late May and early June of 1921 in Tulsa, Oklahoma where it is estimated that approximately 300 people were massacred when white mobs, which included law-enforcement agents and National Guard, assaulted the socially burgeoning and self-reliant Black community.

In recent months, forensic specialists and archaeologists have been engaged in attempts to locate unmarked mass graves where some of the victims were buried. Since July, scientists believe that some of the remains have been located and are seeking the legal requirements necessary to conduct further exhumations and testing.

Phoebe Stubblefield, a forensic anthropologist, has been involved in revealing the truth surrounding the massacre for over two decades. She was present at the Oaklawn cemetery, where the victims are said to have been buried, when the first indications of the remains were found in coffins.

The business district along Greenwood Avenue in Tulsa had become known as “Black Wall Street” due to its thriving independent small businesses which largely served an African American community forced by segregation laws to remain insulated. Despite its adherence to the strict edicts of Jim Crow, the white ruling class interests apparently felt threatened by the initiatives of African Americans who had built their own small enterprises, independent religious institutions, and other organizations.

The centenary of this horrendous series of events slated to be commemorated in another six months, has prompted a reexamination of the Tulsa massacre, falsely described in years past as a “riot.” The only “riot” which took place was the invasion of the African American community by armed racist mobs which looted and burned homes, churches and businesses, while murdering hundreds of people. Thousands of Black people were placed in an open-air detention facility in the aftermath of the events where many remained for several days.

Official accounts of the incident narrated by the white establishment in Oklahoma, denied the scale of the violence including the sheer destruction of property and the number of killings. Nonetheless, oral and documented histories by African Americans have always acknowledged the depth of the concerted attacks and the large number of deaths at the hands of the racists.

A series of documentaries and research studies have revealed the level of carnage carried out during the Tulsa unrest. During the late 1990s, the State of Oklahoma appointed a commission to reconstruct the events of May-June 1921. (https://guides.library.

A commission report issued in 2001 provided riveting accounts of the developments which sparked the murderous mobs and the efforts to suppress the actual horrors committed against the African American community. The racist vigilantes and police agents were acting in response to allegations that a young African American had assaulted a white woman on an elevator in the downtown area.

Corporate newspaper accounts at the time evoked the racist myths surrounding the propensity for Black males to assault innocent white women and called upon the authorities to take immediate action. After the youth who was accused of the assault was arrested, armed African Americans descended on the local jail to prevent a lynching of the man held in detention. Soon there were clashes resulting in shots being fired by African Americans and whites. During the subsequent hours and days, the racist militias invaded the African American community where they engaged in a reign of terror. Later there were reports of airplanes flying overhead in the Greenwood neighborhood where incendiary devices were dropped on homes and businesses.

Tulsa Was Not an Isolated Case

The years between WWI and 1921 were marked by racist attacks on African American communities throughout the U.S. where many were displaced, injured and killed. During the same year that the U.S. entered the first imperialist war, 1917, white racist mobs attacked African American communities in East St. Louis (Illinois), Chester (Pennsylvania), Lexington (Kentucky), Philadelphia, among other cities and rural areas.

After the conclusion of WWI, a renewed round of racial violence occurred across the country. In Elaine, Arkansas, where dozens and perhaps hundreds of African American tenant farmers were massacred after attempting to form a union of sharecroppers and domestic workers, it would take the intervention of anti-lynching fighter Ida B. Wells-Barnett along with the NAACP to prevent the execution of several Black men accused of insurrection. Chicago and Washington, D.C. were some of the worst cities affected when African Americans fought pitched battles with white vigilantes, police officers and National Guard soldiers in the summer of 1919.

These racially motivated conflicts coincided with both an upsurge in industrial labor actions and the continuation of state repression which intensified during the War. Thousands of opponents of U.S. involvement in WWI were imprisoned and deported by the government in 1917-1918. The-then Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer gained a horrendous reputation for anti-Black and anti-Labor political investigations and prosecutions. The Palmer Raids of 1919 were specifically designed to thwart the organization of the working class along with the struggle for equality and self-determination among African Americans.

Consequently, the situation in Tulsa in 1921 was reflective of the generally repressive atmosphere prevailing in the U.S. Therefore, it is not surprising that the authorities in Oklahoma went to great lengths to conceal the crimes committed against the African American people in Tulsa.

Live Science magazine published an article on the research being done in the Sexton section of Oaklawn Cemetery in Tulsa. The report notes that: “The Tulsa race massacre wasn’t officially recognized by the state until 2001, and historians have claimed accounts of the violence were suppressed. But in recent decades, Oklahoma and the city of Tulsa have tried to better come to terms with this brutal part of their history. It’s thought that most people who were alive at the time have now passed away; one of the last known survivors, the psychologist and professor Olivia Juliette Hooker, died in 2018 at the age of 103.” (https://www.livescience.com/

Reparations Recommended and Denied

After the first commission report in 2001, it was recommended that reparations be paid to the survivors of the 1921 Tulsa massacre. Yet there is no record of any reparations given to African Americans living in Tulsa at the time or their descendants.

Leading up to the 100th anniversary of the disturbances, a civil lawsuit has been filed with the lead plaintiff being a 105-year-old survivor of the unrest. Ms. Lessie Benningfield Randle, was a young child in 1921 when thousands of members of the white mob destroyed a 35-block area where more than 10,000 African Americans lived. She is thought to be one of only two survivors of the attacks.

The Guardian newspaper reported on the civil litigation saying: “Randle still experiences flashbacks of bodies stacked up on the street as the neighborhood burned, her attorneys said. Other plaintiffs include the great-granddaughter of J.B. Stradford, who owned the Stradford hotel in Greenwood, the largest black-owned hotel in the United States at the time of the massacre, and grandchildren of people killed. The lawsuit accuses the city of Tulsa, Tulsa county, the then serving sheriff of Tulsa county, the Oklahoma national guard and Tulsa regional chamber of being directly involved in the massacre. The defendants, lawyers allege, have ‘unjustly enriched themselves at the expense of the black citizens of Tulsa and the survivors and descendants of the 1921 Tulsa race massacre’.” (https://www.theguardian.com/

Advocates for African American Liberation and the fight for reparations will be following this most recent case very closely since its outcome will portend much for future claims. The movement for reparations to African people has grown in the last few years with demonstrations, conferences and lawsuits that span from the U.S. to the Caribbean and the African continent.

Source: News Ghana

Photo By: Hulton-Deutsch Collection/Corbis; Oklahoma Historical Society/Getty Images