Freddie Jenkins’ mother attended what is now the last standing African American schoolhouse in Mount Pleasant, S.C., in the 1930s. (Logan Cyrus, The Times)

By Tyrone Beason, Los Angeles Times —

CHARLESTON, S.C. — Five years before the first shots of the Civil War rang out from the harbor here in 1861, alderman Thomas Ryan and a business partner opened Ryan’s Mart at No. 6 Chalmers St.

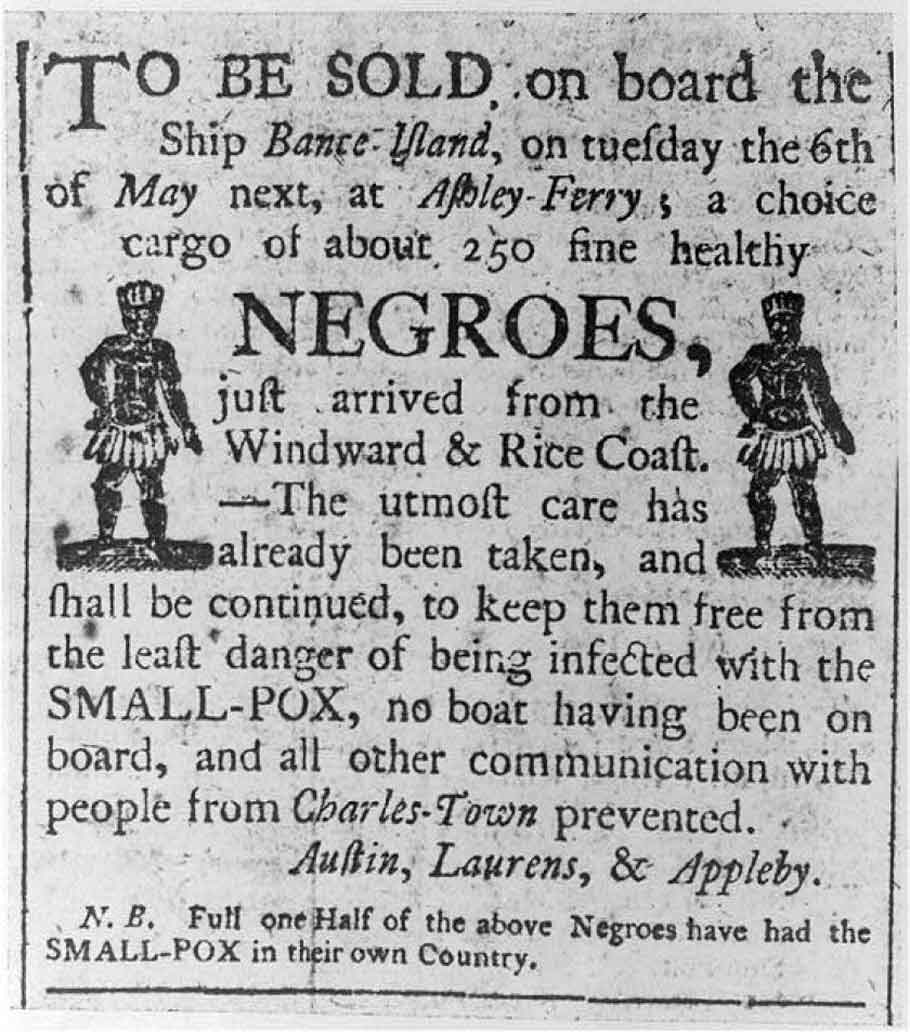

Their merchandise was slaves: African men, women and children who were prodded, picked over and auctioned off to the highest bidders.

The finest adult males could fetch up to $1,600 apiece —$49,000 in today’s dollars. The most able-bodied women could sell for $1,400.

Today, the former showroom in Charleston’s historic quarter, hidden on a narrow lane of row houses blazing with pink blossoms and palmetto trees, serves as the home of the Old Slave Mart Museum.

The museum and other historic sites in the American South lay bare a shameful chapter in the nation’s past, one that’s getting new attention in the debate over whether the government should pay financial reparations to an estimated 40 million descendants of slaves.

The Old Slave Mart Museum in Charleston, S.C., previously a slave auction gallery, educates visitors on the horrors of slavery. (Logan Cyrus, The Times)

Many African Americans in this part of South Carolina support reparations. But they say what they want just as much is for the country to grasp the painful history they live with every day.

Their ancestors often were separated from their children on the auction block. Women were raped by their white owners. Slaves were beaten for waking up too late, not working hard enough or trying to escape. They were stripped of their African names and given the last names of their masters.

The hardship and humiliation didn’t end when the 13th Amendment abolished slavery in 1865. Black Americans continue to endure racist violence, entrenched poverty and inequities in areas such as education, employment and the criminal justice system.

“What the reparations debate is about is not so much people wanting to get money,” said Daniel Littlefield, a historian from Columbia, S.C. “Black people feel they deserve some acknowledgment of ongoing wrong.”

The reparations debate comes at an especially tense time. Since 2016, there’s been a nationwide rise in racially motivated hate crimes. Videos of police killings of African Americans have become all too common. President Trump’s attacks aimed at black leaders and immigrants have kept people on edge.

During July’s Democratic presidential debate in Detroit, a predominantly black city, several candidates stressed the need not only for a discussion of reparations but also of the racial bigotry that still limits African Americans’ prospects nationwide.

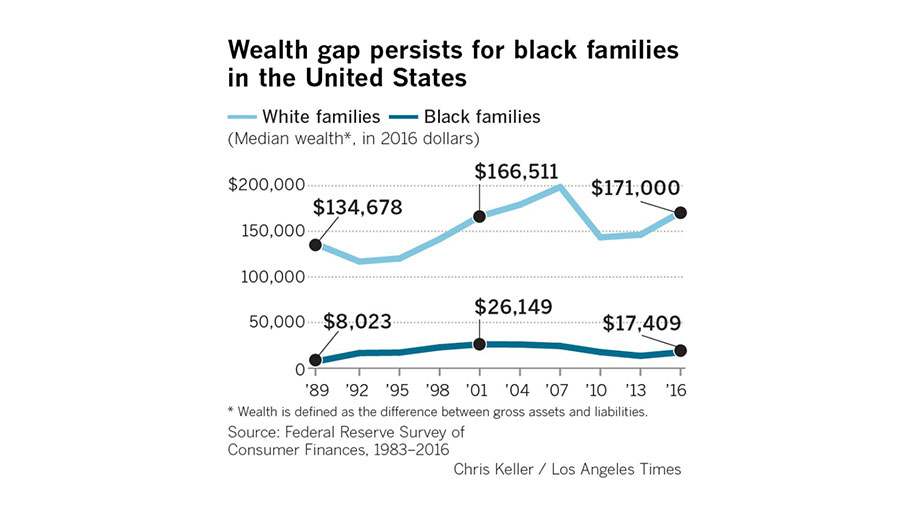

In Los Angeles, black household wealth is about a tenth that of white households, according to a report in 2016 by researchers from UCLA, the New School in New York and Duke University.

A similar wealth gap holds true in metro Charleston, where 40% of black children live below the poverty line.

Roughly half of the two dozen or so Democratic contenders have said they support House Bill 40, which would set up a reparations commission. Several have pitched proposals costing up to half a trillion dollars.

In 2016, white families in the U.S. had nearly 10 times the median family wealth of black families, according to the Federal Reserve’s Survey of Consumer Finances. (Chris Keller, Los Angeles Times)

Americans are split along racial lines on the question of whether to give direct payments to slave descendants, with just 16% of white people backing the idea in a Gallup poll taken in June and July and 73% of black respondents supporting it.

An early newspaper advertisement announcing the sale of slaves at Ashley Ferry outside Charleston, S.C.(Library of Congress)

Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, a Republican from Kentucky whose ancestors owned slaves, echoed the prevailing argument against reparations when he explained his opposition.

“I think we’re always a work in progress in this country, but no one currently alive was responsible for that and I don’t think we should be trying to figure out how to compensate for it,” McConnell said.

Zenobia Harper, a member of the Gullah Geechee people, who are descendants of slaves from this region, says opponents of reparations are missing the point.

“We’re talking about it as though one group of people is trying to get one over on another group of people,” she said.

Activists line up June 19, 2019, for a House Judiciary Committee panel hearing on reparations for the descendants of slaves. (Andew Caballero-Reynolds, AFP-Getty Images)

She thinks Americans must see the story of her people as essential to understanding the nation’s past.

“You were owned as real estate,” said Harper, a cultural preservationist who gives talks on how slaves built the rice plantations in South Carolina that enriched their owners. “You could be mortgaged. You could be leveraged in any way that that person saw fit. You had no redress in court.”

“Everything that you were, everything that you created and procreated, belonged to the people that owned you — in perpetuity,” she said.

The slavery museum highlights the paradox of a region dripping with Spanish moss and Southern hospitality, in a country built on the idea that all are created equal, but whose economy was fueled by the trade in human beings.

On display is a leather whip crudely studded with nails to deliver maximum pain to slaves — to break the skin, and the spirit.

There are other symbols of racial oppression in and around Charleston. The Confederate flag is still proudly flown by some whites here.

On Calhoun Street, at the northern border of a historic quarter filled with soaring church spires, two landmarks highlight the white supremacy of the past and the racism of the present.

One is a statue of former Vice President John C. Calhoun, whose view that slavery represented a “positive good” benefiting captive Africans helped inspire the Southern secessionist movement that led to the Civil War.

A short walk away is Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church, where white supremacist Dylann Roof murdered nine black parishioners in 2015 in a bid to start a war of his own — one pitting whites against blacks.

Democratic presidential candidate Cory Booker used the church as the setting for an impassioned speech on gun violence and white racism in the aftermath of the recent mass shootings in Dayton, Ohio, and El Paso.

A statue of former Vice President John C. Calhoun in Charleston, S.C. His views helped inspire the Southern secessionist movement. (Jabin Botsford, Washington Post)

A civil rights landmark where leaders such as Martin Luther King Jr. once spoke, the church now attracts visitors because of the massacre, which happened two months after a white police officer in North Charleston killed motorist Walter Scott, an unarmed black man.

“A lot of things are still the same,” said Maxine Clark, 58, an African American who came here with her husband from the state capital, Columbia.

“Just what my parents witnessed is what we’re witnessing right now,” said Clark, whose mother is a native South Carolinian. “A black life does not matter.”

The first slaves were brought to America in 1619. By the start of the war, every other person in Charleston was the property of someone else.

“Charleston as we know it wouldn’t exist today without enslaved Africans,” said agricultural historian Richard Porcher, who lives a few miles outside of town and has written about the area’s reliance on slave labor.

All along the 60-mile stretch of Atlantic coastline from Charleston to the historic port of Georgetown to the north, other reminders of what African Americans have endured, and what they’ve accomplished in spite of it, hide in plain sight.

After the Civil War, many freed slaves in the Charleston area set up homesteads on large tracts they purchased from white landowners. The plots have been informally passed down in families from generation to generation, with stakes divided up among relatives often without wills or other legal protections, making the properties vulnerable to outside developers.

Fred Lincoln lives on his family’s ancestral homestead in Wando, an African American settlement a few miles northeast of Charleston.

He and slave descendants from several other homesteads gathered at a house nearby in Old Village to talk about their campaign to preserve what their ancestors built — and to talk about reparations.

“We are damaged people,” Lincoln said of the stress and anxiety that come with being black in America. He wants the government to help descendants of slaves heal emotionally from the scars left by generations of mistreatment.

Lincoln, 74, is a retired firefighter not prone to bursts of emotion. But he switches from sadness to defiance as he reminisces about growing up in the Jim Crow era.

He and the other heirs to homesteads said that in the decades after their ancestors were freed, the former slaves built hundreds of houses using trees from the nearby woods and their skills as carpenters.

Richard Habbershem shows his neighborhood, the Phillips Community, one of the many settlements in South Carolina where former slaves homesteaded and many of their descendants still own land. (Logan Cyrus, The Times)

“We literally lived off the land,” said Thomasena Stokes-Marshall, 76, who was born in the nearby historic black community of Snowden.

Members of the group said their ancestors established a legacy of homeownership in a hostile environment.

In the old days, a driveway barely wide enough for one car often led to a cluster of 10 homes arranged in a circle, so neighbors could look out for each other in case the Ku Klux Klan tried to attack.

Paths leading into the backwoods that black children used as shortcuts were actually escape routes to make it easier to flee Klan raids.

“You built a house with a thought of it being burned down,” said Edward Lee, who grew up in the Scanlonville settlement in the 1950s and ‘60s.

Back then, residents also took turns on “church watch.” “That’s when you slept in the church when it was under threat,” said Lee, 63.

The communities were self-sustaining, with their own schools, stores and nightlife spots. Count Basie and Duke Ellington came through on their tours of segregated venues on the “Chitlin Circuit.” Entertainers would hang out with kids before shows.

“You could play baseball with James Brown,” Lee said.

Today the communities are largely intact, islands of modest homes on large lots along quiet country lanes.

What’s needed now, the property owners say, are tax breaks and other forms of aid to help heirs hold onto these homesteads as new developments spring up around them and property taxes rise.

In any case, Lincoln says, no check from the government can truly account for centuries of injustice.

“My ancestors were robbed of everything — their history, their identity, their culture,” he said. “Giving me money is an insult to my ancestors’ suffering — and all of my suffering.”

Past the African American settlements on the way to Georgetown, Gullah Geechee basket weavers earn a modest living selling handwoven sweetgrass baskets from roadside kiosks. Their ancestors used the same skills on the rice plantations.

On the bridges spanning the Santee River Delta, views open up of a vast tidal wetlands undulating with tall, green grass as far as the eye can see.

Between the 1600s and the Civil War, according to historians, thousands of slaves had to contend with snakes, mosquitoes and disease as they transformed these former cypress swamps into rice farms fed by canals they dug by hand, making the plantation owners some of the richest people in the country.

Slave children ran up and down the levies banging pans together to scare birds away from the rice harvest, while older girls pounded rice husks in wooden mortars.

The Button, a former juke joint, sits in disrepair in the Snowden Community in Mount Pleasant, S.C. Such settlements were built by former slaves to be self-sufficient and to repel Ku Klux Klan attacks. (Logan Cyrus, The Times)

The taming of the tidal wetlands has been compared to the building of the Egyptian pyramids because of the incredible feats of engineering prowess, agricultural skill and physical might involved.

“How in the hell they did that with slave labor — it’s beyond human understanding,” Porcher said. “I still can’t grasp it.”

Porcher, 80, is white, but the reparations issue is personal for him, too. He’s a descendant of aristocratic rice planters who owned thousands of slaves on hundreds of acres of plantations in the region. He lives not far from some of the black settlements.

Any frank discussion about the suppressed economic fortunes of African Americans will require white people to acknowledge the advantages that might have disproportionately expanded their own wealth, Porcher said.

“I’m not going to apologize for my folks owning slaves,” he said, “but I know that I benefited from it.”

Historical researcher Vennie Deas Moore, who lives in Georgetown, was part of a team that recently excavated the foundation of a slave dwelling at the Hampton Plantation outside that city. She believes her slave ancestors on her father’s side were born there and worked on the surrounding rice fields.

“I couldn’t escape having this feeling that the spirits of my family were out there with me,” said Deas Moore, 70. “I felt at peace.”

She laughs when people bring up the idea of the government writing her a check for her ancestors’ hardships.

“I don’t want money,” she said, raising her voice. “What I want the government to do is educate our children so they can be engineers and builders — like their great-great-great-granddaddies were.”

She wants Americans to muster the courage to face the wrongs of slavery and inequality — and take responsibility.

“We’re just starting to tell this story,” Deas Moore said. “It’s not for the weak of heart.”