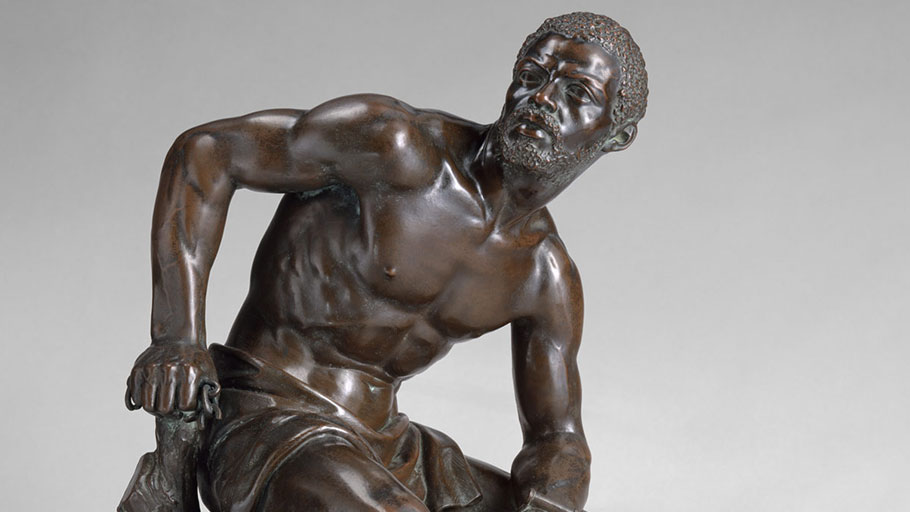

The Freedman. Artist: John Quincy Adams Ward. 1863

By Thomas A. Foster, History News Network —

Editor’s note: This is an excerpt from Rethinking Rufus: Sexual Violations of Enslaved Men by Thomas A. Foster. Reprinted with permission from The University of Georgia Press.

Editor’s note: This is an excerpt from Rethinking Rufus: Sexual Violations of Enslaved Men by Thomas A. Foster. Reprinted with permission from The University of Georgia Press.

The promise of freedom may also have been used to entice enslaved men into sexual contact with white women. In eighteenth-century Pennsylvania, one court record of punishment meted out to a white woman and an enslaved man for having a child together sentenced her to be whipped and ordered him to “never more” “meddle with white women uppon paine of his life.” When the man was examined by the court he defended himself by complaining that she had “intised him and promised him to marry him.” His version was corroborated by the woman, who “confest the same.” Was this a promise to free him? Did she entice him and promise to marry him, or was the promise of marriage part of the enticement?

A similar case suggests that a promise of freedom may have figured as a method of enticement. In 1813 an enslaved man named David was convicted of rape in Virginia. In a petition to the governor in David’s defense, one neighbor testified that the woman Dolly Getts had in fact engaged in “improper intimacy” with David for three years prior to the rape accusation. Dolly and David were known by her father to “bed together” in the father’s house. He contended that Dolly had “admitted” that David’s “improper conduct arose from her persuasions, that she frequently made use of great importunities to the said David for the purpose of prevailing on him to run off with her which he for some time refused to accede to.” Several times she apparently convinced David to spend time together miles away from the house. On one such occasion, she “earnestly solicited David to go to her father and tell him they were married and perhaps they might be permitted to remain together.” Unwilling to take these risks, “David refused and charged her with having brought him into his then unpleasant situation.” In another related example, in 1826 a white woman was captured after having stolen a horse and an enslaved man. She had disguised herself as a man, and according to the account, “she persuaded him off and that she was the whole and sole cause of his stealing his master’s horse.” The enslaved man was punished for the theft of the horse.

The promise of freedom was probably less common than the threat of selling an enslaved man away. Court testimony from an 1841 Kentucky case involved an enslaved man and a white woman who lived together as husband and wife and whose case had come to court over the woman’s ability to sell her own land. The court declared that their relationship was not marriage but was instead one of “concubinage.” Moreover, the case included testimony that revealed the power dynamic within the relationship, since it was reported that the white woman “sometimes threatend to sell” the man, James, “when vexed with him.” Another neighbor testified that he “frequently heard her threaten to sell him if he did not behave himself.” In a related example, William Thomas complained that his wife, Sarah Jane, knew that he was going to sell an enslaved man, “for previously on two occasions defendant had found said negro too near Petitioner’s Bed in the night time and slipping away from her Bed privately.” The threat of being sold was a constant fear for enslaved people; it included the terror of being sold to southern states and the West Indies, known for brutal conditions and higher mortality rates, and the pain of being wrenched away from loved ones, kin, and community.

Violations of privacy included punishments that involved nakedness; the threat of such physical punishment could also be wielded by some women. One former slave described his mistress as whipping him: “Mr. Hammans was a very severe and cruel master, and his wife still worse; she used to tie me up and flog me while naked.” Another man described his mistress in similar terms, emphasizing physical contact that occurred after being “stripped naked”:

His wife was a harsh, cruel, hardhearted, tyrannical woman, her whole being was filled with hatred of the blackest and bitterest kind against the poor down-trodden, crushed, despised and trampled slave; she seemed possessed with some Satanic influence, and never was in her glory unless she could have her slaves tied up to the whipping post, stripped naked, with a pair of flat irons fastened to their feet, then she would stand by, drawing the lash like an infuriated demon, all the nicer sensibilities of her womanly nature seemed to be crushed out of existence. She would ply the lash until the poor victim would faint dead away.

Hinton’s testimony also revealed something about the variety of tactics that women employed toward men in such circumstances, many of them strikingly similar to the strategies employed by white owners against black women: “I have generally found that, unless the woman has treated them kindly, and won their confidence, they have to be threatened, or have their passions aroused by actual contact.” Here we see that direct threats accompanied some of these relationships, or indirect manipulation, with a subtler threat of violence. Once physical contact and arousal had been achieved, a man might have little ability to resist.

Regardless of the circumstances that prompted these varied arrangements, many of them clearly took place in the context of servitude and highlighted the power of the enslaving woman over the enslaved man. Harriet Jacobs, in her mention of a white woman who preyed on an enslaved man, wrote that she had picked a man who was “the most brutalized, over whom her authority could be exercised with less fear of exposure.” Anecdotes such as these suggest that some white women initiated sexual encounters and made clear what they wanted, knowing that their cultural role, the sexual innocence expected of them, helped to hide their actions. Jacobs’s account noted that she was personally familiar with this household. Her account also suggested that the woman preyed on more than one man. She “did not make advances . . . to her father’s more intelligent servants” but singled out for sexual assault instead a man “over whom her authority could be exercised with less fear of exposure” because he was so traumatized. Such a man, it is suggested, had been terrorized into submission on the plantation, and she took advantage of his state of mind to force herself upon him—with the threat of additional punishment if he did not accept her assault and if he did not keep it clandestine.

Wives and daughters of planters who formed these sexual relationships took advantage of their position within the slave system. Having sex with their white counterparts in the insular world of the white planter class, if exposed, would certainly have risked opprobrium, and even gossip about the women’s actions might have marred their reputations. Daughters of planters could use enslaved men in domestic settings, however, retain their virtue, and maintain the appearance of passionlessness and virginity while seeking sexual experimentation. In other words, one of the ways that some southern women may have protected their public virtue was by clandestine relations with black men. Hinton also told the AFIC that a white doctor reported to him that in Virginia and Missouri “white women, especially the daughters of the smaller planters, who were brought into more direct relations with the negro, had compelled some one of the men to have something to do with them.”

Sons of planters also engaged in such conduct, as Hinton also noted, even suggesting that young women imitated the behavior of their brothers. Hinton explained that some daughters of wealthy individuals on the American frontier, where interactions with male suitors were also relatively limited, as they were for planters’ daughters, given social constraints, “knew that their brothers were sleeping with the chambermaids, or other servants, and I don’t see how it could be otherwise than they too should give loose to their passions.” Another man reported that the conditions of slavery not only brought about the “promiscuous intercourse among blacks, and between black women and white men” but also created a context that encouraged white women to be “involved” in the “general depravity.” Harriet Jacobs wrote that daughters “know that the women slaves are subject to their father’s authority over men slaves” and therefore “selected” and coerced certain enslaved men to be sexual partners. Although Hinton and Jacobs perhaps could not conceive of women taking the initiative on their own and understood them as following the example set by their fathers and brothers, we should note that daughters seem to have engaged in the same behavior as fathers and sons, if not perhaps as many. Although clearly from Jacobs’s testimony, field hands were abused, we should also note that house slaves, given their closer proximity to white women, would have fallen under special control.

White women’s sexual exploitation of enslaved men may well have led to marital tensions among enslaved couples. In antebellum Alabama, one white man petitioned for divorce and alleged that his wife had been “delivered of a black child, the fruits of illicit intercourse carried on between the said Matilda [his wife] and a negro slave” owned by her father. Loren Schweninger uses the case as an example of how enslaved people sometimes seized opportunities to run away when husbands and wives, and thus households, were disrupted. In this case, the enslaved man’s wife ran away at this time. It might also be worth pondering this case from a different angle. What would have been the experience of this enslaved man? His master’s daughter, Matilda, engaged him in sexual relations. His wife ran away. Was love lost? Was he able to say no to Matilda? Or did she break up this enslaved family, with the man’s wife running away to escape an unbearable situation?

From Rose’s interview we glean no indications about Rufus’s experiences with white women other than that his mistress played a key role in his forced coupling with Rose. Sexual relations between white women and enslaved black men were well known in early America and resulted in court and church pronouncements and punishments, cultural derision, and the dissolution of white marriages. Efforts to police intimate relations between black men and white women stemmed in part from a desire to control women. Such behavior threatened white men and their authority over white women’s sexuality. Discussions of these relationships have often taken their cues from late nineteenth-century understandings of white women’s passive victimhood and black male sexual aggression, but even a cursory examination of the extant records surrounding these interactions suggests that much more was at work in these deeply fraught interactions. The relative power that white women had over enslaved black men’s bodies and their lives and circumstances makes it possible for us to view their sexual relations as defying white patriarchal authority but at the expense of enslaved men and their families, kin, and communities. Whatever white women’s actions accomplished in terms of solidifying their own autonomy was not equally shared by the enslaved men with whom they had intimate relations. Those men lived under constant threat of punishment and could only carefully navigate and negotiate the thorny path that white women presented them whenever sexual intimacy occurred. One wonders if the myth of the black rapist that emerged after emancipation, the fiction that black men uncontrollably sought sexual contact with white women, was not partly informed by white women justifying their actions during enslavement—and their fear of revenge.

Thomas A. Foster is an associate dean for faculty affairs and a history professor at Howard University. He is the author of Sex and the Eighteenth-Century Man: Massachusetts and the History of Sexuality in America and Sex and the Founding Fathers: The American Quest for a Relatable Past.