The revolt of the Anglo colonists was more than an independence movement—it was, in word and deed, a counter-revolution against the advancing trend of human liberation that was sweeping the world.

Richard D. Vogel, Monthly Review Online —

The author wishes to acknowledge the insight provided by of the works of Gerald Horne, especially The Counter-Revolution of 1776, in the development of this thesis.

The official history of the Texas Revolution is engraved in stone on the monument at the San Jacinto Battleground near Houston. The statement of the final outcome of the conflict with Mexico is remarkably candid:

MEASURED BY RESULTS, SAN JACINTO WAS ONE OF THE DECISIVE BATTLES OF THE WORLD. THE FREEDOM OF TEXAS FROM MEXICO WON HERE LED TO ANNEXATION AND TO THE MEXICAN WAR, RESULTING IN THE ACQUISITION BY THE UNITED STATES OF THE STATES OF TEXAS, NEW MEXICO, ARIZONA, NEVADA, CALIFORNIA, UTAH AND PARTS OF COLORADO, WYOMING, KANSAS AND OKLAHOMA. ALMOST ONE-THIRD OF THE PRESENT AREA OF THE AMERICAN NATION, NEARLY A MILLION SQUARE MILES OF TERRITORY, CHANGED SOVEREIGNTY.

This is a spot-on history of the birth of the American empire. But beyond recounting the regional and national events celebrated on the monument, re-viewing the Texas revolution in a world-historical perspective offers a far more insightful understanding of the conflict that occurred in northern Mexico in the 19th century. The revolt of the Anglo colonists was more than an independence movement—it was, in word and deed, a counter-revolution against the advancing trend of human liberation that was sweeping the world.

The Historical Setting

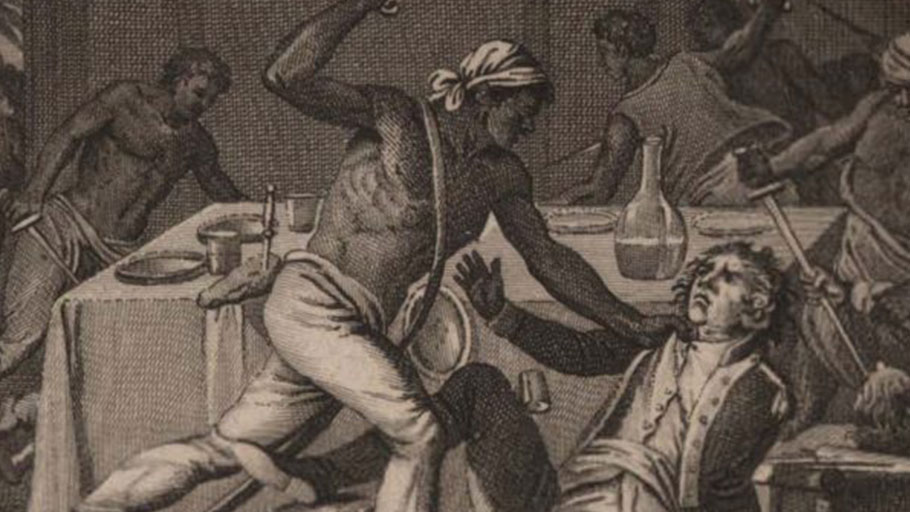

By the beginning of the 19th century slavery in North America was facing growing opposition. Here are the highlights of the anti-slavery movement up to the time of the Texas counter-revolution:

- 1738 Fort Mosé, Florida. The first legal settlement for free Blacks in North America was established by Spain as a refuge for runaway slaves from the British colonies. The existence of this sanctuary likely inspired the Stono Rebellion in South Carolina in 1739, the largest slave uprising in the history of British mainland colonies.

- 1787 Congress passed the Northwest Ordinance outlawing slavery in the Northwest Territories.

- 1793 The importation of slaves into Canada was banned.

- 1794 The Slave Trade Act prohibited American ships from participating in the slave trade and the importation of slaves on foreign ships.

- 1800 Americans were banned from investment or employment in the slave trade.

- 1804 By 1804 all northern U.S. states had abolished slavery. All of the southern and border states allowed slavery until the American Civil War.

- 1808 The importation and exportation of slaves became a crime in the U.S.

- 1810 The first leader in the Mexican revolt against Spain, Father Hidalgo, issued several decrees demanding the manumission of all slaves on pain of death.

- 1813 Mexican independence leader José Maria Morales declared in his Sentimientos de la Nación, “slavery is forbidden forever”.

- 1816 The destruction of Negro Fort in Spanish Florida.

- 1820 The Compromise of 1820 banned slavery in the U.S. north of the 36030’ line.

- 1824 The new constitution of Mexico formally abolished slavery and by 1829 the last slaves were freed.

- 1834 Slavery was abolished in Canada.

- After 1834 the underground railroads for runaway slaves from the U.S. to Florida, Mexico, and Canada expanded, threatening the existence of the institution.

This timeline of the advance of liberty set the stage for the Texas counter-revolution of 1836, and the destruction of Negro Fort offers a brutal prelude to the impending conflict.

The Destruction of Negro Fort

Negro Fort was built by the British as a southern base of operations during the War of 1812. It was located a on a bluff commanding the Apalachicola River in northwest Spanish Florida. After being abandoned by the British (along with copious supplies of arms and ammunition) the fort became a stronghold for runaway slaves from southern states allied with native maroons and their Seminole allies. General Andrew Jackson recognized Negro Fort as a dire threat to slavery in the U.S. and ordered General Edmund Gaines to destroy it:

I have little doubt of the fact, that this fort has been established by some villains for rapine and plunder, and that it ought to be blown up, regardless of the land on which it stands; and if your mind shall have formed the same conclusion, destroy it and return the stolen Negroes and property to their rightful owners.

Gaines assigned the operation to Lt. Colonel Duncan Lamont Clinch.

In the company of Creek Indians who had been hired by General Jackson to hunt down runaway slaves, Colonel Clinch and his detachment of soldier proceeded to Negro Fort where they were fired on by the fort’s defenders and forced to wait for the arrival of gunboats. On July 27th the gunboats arrived and, after firing some cold shots to establish the range, shot a red-hot cannon ball into the fort where it hit the powder magazine. The fort was completely destroyed.

Clinch described the scene:

The explosion was awful, and the scene horrible beyond description. You cannot conceive, nor I describe the horrors of the scene. In an instant, lifeless bodies were stretched upon the plain, buried in sand or rubbish, or suspended from the tops of surrounding pines. Here lay an innocent babe, there a helpless mother; on one side a sturdy warrior, on the other a bleeding squaw. Piles of bodies, large heaps of sand, broken guns, accoutrements, etc, covered the site of the fort. The brave soldier was disarmed of his resentment and checked his victorious career, to drop a tear on the distressing scene.

Two hundred and seventy of 330 defenders and refugees in Negro Fort—men, women, and children—were killed outright. The Black commander of the fort, who survived the blast, was executed on the spot. The Blacks that were captured were sent to slavery in Georgia while other survivors managed to escape into the forest.

The sanctuary for runaway slaves at Negro Fort was completely obliterated.

The men who ordered and oversaw the destruction of Negro Fort—Generals Jackson and Gaines—both reappeared 20 years later to play key supporting roles in the Texas counter-revolution.

Run-Up to the Conflict in Mexico

Leaders on both the Anglo and the Mexican sides of the conflict in northern Mexico knew that the future of slavery was the issue at hand.

Stephen F. Austin, the Missouri expatriate who arranged for Anglo immigration to Mexico in 1821, encouraged migration from the U.S. with generous land grants for heads of households, their wives, and children. Simultaneously he, himself a slave owner, promoted the extension of slavery from the southern U.S. into Coahuila y Tejas by granting 80 additional acres for every slave that immigrants brought with them.

On the eve of the counter-revolution in 1835 (after 14 years of immigration by Anglo settlers) Austin emphasized the role of slavery in the conflict with the Mexican government:

The situation of Texas is daily becoming more interesting, so much so, that I doubt whether the Government of the United States, or that of Mexico, can much longer look on with indifference, or inaction. It is very evident that the best interests of the United States require that Texas should be effectively, and fully, Americanized— that is—settled by a population that will harmonize with their neighbors on the East, in language, political principles, common origin, sympathy, and even interest. Texas must be a slave country. It is no longer a matter of doubt [emphasis in the original]. The interest of Louisiana requires that it should be, a population of fanatical abolitionists in Texas [anti-slavery Mexicans] would have a very pernicious and dangerous influence on the overgrown slave population of that state.

Mexican officials were aware of, and opposed to, the activities of the Anglo slave traders in Texas.

In his Relations Between Texas, The United States, and The Mexican Republic, Mexican General José MaríaTornel clearly defined the international conflict over the issue of slavery:

As a matter of fact, without having proclaimed as pompously as the United States the rights of man, we have respected them better by abolishing all distinctions of class or race and considering as our brothers all creatures created by our common father. The land speculators of Texas have tried to convert it into a mart of human flesh where slaves from the south might be sold and others from Africa might be introduced, since it is not possible to do it directly through the United States.

In his Manifesto, General Antonio Lopez de Santa-Ana, President of the Republic of Mexico and commander of the punitive expedition against the slave holding rebels in Texas, reiterated the Mexican position on slavery quite clearly on the eve of his campaign:

There is a considerable number of slaves in Texas also, who have been introduced by their masters under cover of certain questionable contracts, who according to our laws should be free. Shall we permit those wretches to moan in chains any longer in a country whose kind laws protect the liberty of man without distinction of cast or color?

The marching orders that Santa Ana issued to his generals before he launched his expedition were unequivocal and included the following decree:

All negros should be liberated and declared free.

The stage was set for anotherclash between the forces of liberation and the forces of reactionwitnessed at the destruction of Negro Fort—and the same key players in the United States were involved in both events.

The Clash

Here are the highlights of the military confrontation between Mexican and Anglo forces in Texas:

Matagorda, September 1, 1835

The duel between the American registered schooner San Felipe and the Mexican revenue cutter Correro de México was the first military engagement of the Texas counter-revolution. TheSan Felipe, owned by Thomas F. McKinney, a slaveholder and financier of the Anglo rebellion, had just unloaded arms and freebooters from New Orleans destined for Brazoria when it was challenged by the Correro. In the ensuing exchange of cannon and rifle fire, the Mexican ship was damaged and the captain and most of the crew were wounded. The Correro put to sea but was overtaken and captured by the San Felipe. The Mexican ship and survivors were taken to New Orleans where the captain and crew were charged with piracy under U.S. maritime law.

Gonzales, October 2, 1835

The so-called Battle of Gonzales was actually an ambush. It took place after the Mexican military commander in Texas dispatched 100 dragoons under the command of Lieutenant Francisco de Castañeda to retrieve a cannon lent to the Anglo colonists of Gonzales in 1831 for defense against Indians. The settlers stalled for time and overnight enlisted more than 140 volunteers from surrounding communities to bolster resistance. On the morning of October 2, the Anglo settlers attacked the Mexicans without provocation or warning. Castañeda, under strict orders not to provoke the settlers, withdrew from the confrontation.

Laredo, January, 1836

Santa Ana crossed the Rio Grande with a force of 6,000 troops and headed for San Antonio.

The news of Santa Ana’s advance caused widespread panic among the slaveholders in southeast Texas who knew of his emancipation decree. Driving their valuable slaves before them at gun point, the Anglo settlers began their panicked flight towards Louisiana (the storied Runaway Scrape).

About the same time General Edmond Gaines, then commander of the Southwest Military District of the U.S. under Andrew Jackson (elected President in 1829), stationed his forces near Fort Jessup located on the Old San Antonio Road on the Louisiana side of the Sabine River, waiting to intervene on behalf of the Anglo settlers in the Texas counter-revolution. While encamped there, Gaines facilitated the river crossing of armed freebooter volunteers from Louisiana, Alabama, Mississippi, and Missouri.

San Antonio, February 23, 1836

Santa Ana arrived in San Antonio and began a 13-day siege of the Anglo rebels invested in the Alamo mission.

Fort Jessup, Louisiana, February 29, 1836

General Gaines ordered the Sixth U.S. Infantry Regiment stationed at Jefferson Barracks near St. Louis to Fort Jessup as a reserve force in his preparation to cross the Sabine.

San Antonio, March 6, 1836

The fall of the Alamo on March 6 was a terrible defeat for the Anglo rebels. All of the defenders of the mission under the joint command of slaveholders James Bowie and William B. Travis, were killed, while Santa Ana lost some 600 of his men. At least 30 non-combatants survived the siege, mostly slaves who were set free, but also a number of women and children who had sought refuge inside the walls of the mission.

After the fall of the Alamo Santa Ana sent one of the captured flags back to Mexico City. It was a blue silk banner displaying an eagle and sunburst with the inscription: “FIRST COMPANY OF TEXAN VOLUNTEERS! FROM NEW ORLEANS”. In the accompanying letter addressed to General José María Tornel, the minister of war and navy, Santa Ana observed:

The bearer takes with him one of the flags of the enemy’s battalion captured today. The inspection of it will show plainly the true intention of the treacherous colonists and of their abettors who came from parts of the United States of the North.

Five days later, Sam Houston (a slaveholder himself and President Jackson’s protégé), the newly appointed Commander of the Texas Army, learned of the fall of the Alamo and ordered the evacuation of all Anglo settlers toward Gaines’s position on the Sabine. Houston knew that Gaines was waiting to engage Santa Ana’s forces if they crossed the Trinity River in east Texas.

Goliad, March 27, 1836

The massacre at Goliad was an infamous event. James Walker Fannin, a notorious slave trader, and the men under his command (some 300 adventurers and freebooters from New Orleans) were captured by Mexican soldiers under the command of General José de Urrea near Coleto Creek on March 20. The prisoners were marched to Goliad, where, one week later, under strict orders from Santa Ana, they were executed as pirates. The flag captured at Coleto Creek and sent back to Mexico City was the red battle ensign of the Red Rovers, freebooters from New Orleans.

“REMEMBER GOLIAD!”, like “REMEMBER THE ALAMO!”, became a battle cry of the Anglos at the Battle of San Jacinto.

San Jacinto, April 21, 1836

The climax of the Texas rebellion took place soon after many of the Anglo settlers who had joined the Runaway Scrape refused to follow Houston to the rendezvous with Gaines in east Texas and turned southeast toward Harrisburg (Houston) to confront the Mexican army under Santa Ana. The subsequent battle of San Jacinto on April 21 was a decisive victory for the Texas counter-revolution. According to Houston’s official report, the casualties were 630 Mexicans killed and 730 taken prisoner. Against this, only nine of the 910 Texans were killed or mortally wounded and thirty were wounded less seriously. Santa Ana was captured and on May 14th he signed a treaty of capitulation at Velasco.

Houston, wounded at San Jacinto and evacuated to Louisiana for medical treatment, was celebrated as a hero when he arrived in New Orleans.

After receiving news of the Anglo victory at San Jacinto, General Gaines transferred most of the troops under his command to New Orleans from where they were shipped to Florida to serve as reinforcements in the ongoing Second Seminole War against runaway slaves, maroons, and Seminole Indians.

The fact that the Mexican government repudiated the Treaty of Velasco signaled that the conflict between the two nations remained unresolved.

The Upshot

The victory of reaction over the progress of liberty was enshrined in the constitution of the new Republic of Texas adopted on March 16, 1836:

Sec. 9. All persons of color who were slaves for life previous to their emigration to Texas, and who are now held in bondage, shall remain in the like state of servitude: provided, the said slave shall be the bona fide property of the person so holding said slave as aforesaid. Congress shall pass no laws to prohibit emigrants from bringing their slaves into the republic with them, and holding them by the same tenure by which such slaves were held in the United States; nor shall congress have power to emancipate slaves; nor shall any slave holder be allowed to emancipate his or her slaves without the consent of congress, unless he or she shall send his or her slaves without the limits of the republic. No free person of African descent, either in whole or in part, shall be permitted to reside permanently in the republic, without the consent of congress; and the importation or admission of Africans or negros into this republic, excepting from the United States of America, is forever prohibited, and declared to be piracy.

The forces of reaction clearly won the Texas counter-revolution of 1836 but the historical conflict with Mexico was far from over. Open hostilities resumed less than a decade later with the U.S. annexation of Texas and the resulting U.S. invasion of its southern neighbor during which the conflict reached its highpoint.

The culmination of the struggle is the topic of the upcoming “The Counter-Revolution Thwarted: Popular Resistance and the Failure of The Movement for the Occupation of All Mexico”.

Richard D. Vogel (rd_vogel [at] msn.com) is an independent socialist writer who has contributed to Monthly Review in the past. He was a contributor to More Unequal: Aspects of Class in the United States published by MR in 2007. He is also the author of numerous articles including: “The NAFTA Corridors: Offshoring U.S. Transportation Jobs to Mexico,” “Transient Servitude: The U.S. Guest Worker Program for Exploiting Mexican and Central American Workers,” and “The Fight of Our Lives: The War of Attrition against U.S. Labor”.