The grand buildings of Bordeaux, France, were financed, in part, by the trans-Atlantic slave trade. The city has moved to address that past. Credit: Andrea Mantovani for The New York Times

Rather than tear down statues, some argue that the past should not be obliterated, but remembered and explained.

By Norimitsu Onishi, The New York Times —

BORDEAUX, France — At a bend in the river, a succession of stately stone buildings, each more imposing than the last, stretches along the left bank. Their elegant 18th-century facades had helped Bordeaux, already famous for its wineries, become a UNESCO World Heritage site.

“This facade, it’s a monumental and extraordinary heritage — and a sort of stage metaphor,” said Laurent Védrine, director of the Museum of Aquitaine. “Let’s go look behind the stone facade: Where did this wealth come from?”

Bordeaux, unlike much of France, began digging into that question more than a decade ago. It found that its grand buildings had been financed, in part, by the slave trade. Slavery touched on its monuments and its architecture. So the city began to address the past, but instead of tearing down the telltales of its ugly history, it has put up plaques to acknowledge and explain it.

Other European cities with similar histories have preferred to remain silent. But the killing of George Floyd by a police officer in Minneapolis has now widened and invigorated the debate over Europe’s long, brutal and lucrative history in Africa, punctuated by the recent toppling of statues of colonial-era figures.

In France, a long history of slavery and colonialism has been eclipsed by a national narrative and self-identity as the revolutionary champion of universal human rights.

Karfa Diallo, founder of an organization that has pushed the city to acknowledge its history, guiding visitors along routes that reveal traces of Bordeaux’s role in the trans-Atlantic slave trade. Credit: Andrea Mantovani for The New York Times

But France’s colonialist past is a subject as sensitive as slavery is in the United States. Behind the refined facade of much of Europe, the world’s most-visited tourist region, lies wealth that was generated by the trans-Atlantic slave trade and the subsequent colonization of the African continent.

Many decades after most African nations gained independence, there has been no complete coming to terms with that history, either in Europe or in Africa. Caught in the silence are people of African origin in Europe, where enduring racism, near-hysterical fear over migration and the failure to integrate generations of immigrants cannot be separated from that unresolved past.

“It’s the inability to shed light on that past that maintains the racism and the impunity of the police, or the impunity of those who make decisions, in employment or in housing, based on physical criteria and deny the rights of French people who are black or Arab,” said Karfa Diallo, the Senegalese-born founder of Mémoires et Partages, an organization that has pushed the city of Bordeaux to fully acknowledge its history. “It’s never said as clearly as that, but that’s the heart of the matter.”

As researchers dug deeper into Bordeaux — past the sculpted African faces looking down from a building in the Place de la Bourse — they found logbooks, records, paintings, all showing that the French city in the interior, at a bend in the Garonne, had flourished because of commerce based on the enslavement of human beings.

The Place de la Bourse is a symbol of the prosperity of the city of Bordeaux. Credit: Andrea Mantovani for The New York Times

Local men had made fortunes sending ships to Africa, where the French bartered goods for people, who were then taken across the Atlantic to Caribbean colonies. There, they were sold and forced to labor on plantations, producing goods that were finally brought to Bordeaux’s port and sold in Europe.

In 2009, the Museum of Aquitaine established a permanent exhibition detailing Bordeaux’s role in France’s slavery-based commerce. From 1672 to 1837, 180 shipowners in Bordeaux led 480 expeditions that transported as many as 150,000 Africans to France’s Caribbean colonies, making Bordeaux the most important French slave-trading port after Nantes.

The city government has physically acknowledged that history, starting in 2006 with a modest plaque on a dock along the river to commemorate the history of slavery. Over the years, the reminders have grown more prominent and moved closer to where people live. Last year, the statue of Modeste Testas, an enslaved woman bought by two Bordeaux brothers, was erected on the riverbank.

This month, the city installed plaques on five residential streets named after prominent local men who were involved in the trans-Atlantic slave trade. One plaque, placed on the wall of a one-story house on Gramont Street, explained that Jacques-Barthélémy Gramont, a former mayor of Bordeaux, financed a slave-trading expedition in 1783 and two more in 1803.

This year, Bordeaux installed explanatory plaques on streets bearing the names of men involved in the slave trade. Credit: Andrea Mantovani for The New York Times

Marik Fetouh, a deputy mayor, said that the city had always believed that the past must be remembered and explained, in contrast to a growing number of people pushing to tear down statues in Europe and the United States.

“Getting rid of statues won’t erase horrible crimes that have been committed,” Mr. Fetouh said. “Not only do you not change history, but you also deprive yourself of ways of explaining it.”

But Mr. Diallo said that Bordeaux — and France — should do more, especially in light of the anger stirred by Mr. Floyd’s killing. Mr. Diallo said that while he found the possibility of financial reparations politically unrealistic, he believed the idea was morally just: When France abolished slavery in 1848, it compensated enslavers for their financial loss. Far short of that, he says, he’d like to see one street in the city renamed entirely as a “strong symbol.”

Mr. Fetouh said that changing street names makes residents angry and would make the population less open to look at the past. But around Europe there is less sentiment in favor of preserving the status quo.

After Mr. Floyd’s killing, a crowd in Bristol, England, toppled a statue of the 17th-century slave trader Edward Colston. In Antwerp, Belgium, the local authorities, responding to increasing protests, removed a statue of Leopold II, the Belgian king who ran an exploitative regime that led to the deaths of millions in what is now the Democratic Republic of Congo and whose ambitions set off Europe’s scramble for African colonies.

In the United States, protesters first focused on Confederate monuments. But they have since cast a wider eye, including at former presidents like Andrew Jackson, a slave owner whose policies forced Native Americans from their land, and Woodrow Wilson, the architect of the League of Nations whose legacy has faced increasing scrutiny for his racist views and his resegregation of the federal work force.

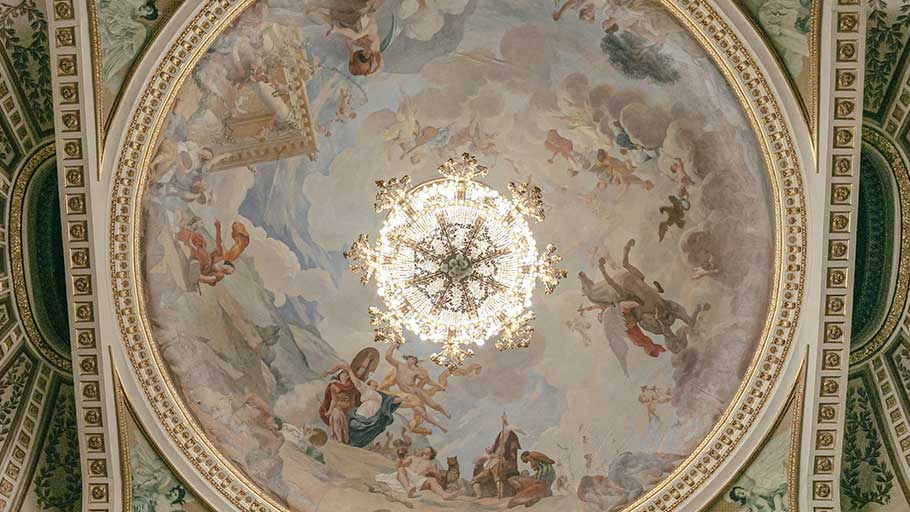

A fresco on the ceiling of a Bordeaux theater showing the city’s 18th-century wealth, which was based in part on slavery-based commerce. Credit: Andrea Mantovani for The New York Times

In France, many protesters focused on Jean-Baptiste Colbert, the 17th-century statesman who is still celebrated for his lasting impact on France’s political economy, but who was also the author of the Code Noir, the 1685 decree regulating slavery in the colonies. On Tuesday, a protester splattered red paint on a statue of Colbert in front of the National Assembly and wrote “state Negrophobia” on its pedestal.

Jean-Marc Ayrault, a former prime minister who is now president of the Foundation for the Memory of Slavery, urged the government to remove Colbert’s name from important halls and buildings. The idea was quickly shot down, led by President Emmanuel Macron, who said during a national address that France “will not erase any trace or name from its history. The republic will not take down any statues.”

But France — whose diplomatic power rests greatly on the influence it still exerts over its former African colonies — has struggled more than other European nations to come to terms with its imperial past.

Models of ships displayed at the Museum d’Aquitaine. Many men in Bordeaux made fortunes sending ships to Africa, where they bartered goods for people. Credit: Andrea Mantovani for The New York Times

Achille Mbembe, a Cameroonian expert on post-colonial history and France, said that those efforts were complicated by France’s self-understanding as a nation and as a proponent of universal values like equality and liberty.

“There aren’t that many countries in the world which believe profoundly that they are invested with a universal mission,” said Mr. Mbembe, who teaches at the University of Witwatersrand in Johannesburg. “The U.S. is one of them, and France is the other.”

“It is the idea of a universal which is premised on the concept that there is one human race,” he added. “But the French confuse the horizon with the existing reality. There’s a huge gap.”

The gap was easy to ignore because slave-trading and colonialism were carried out well beyond France’s main territory in Europe, Mr. Mbembe said, adding, “It was always a kind of offshore enterprise.”

Even in France’s far-flung corners, coming to terms with the past has been a slow process.

In French Guiana — an overseas department on the north coast of South America that France established in the 17th century with enslaved Africans — the main airport was long named “Rochambeau” after the father of a French general who used dogs to suppress a slave uprising in Haiti and encouraged feeding the dogs with human flesh.

Christiane Taubira — a lawmaker who was the driving force behind a 2001 French law that recognized the slave trade and slavery as crimes against humanity, and the first black woman named justice minister in France — began pressing to change the airport’s name in the early 2000s.

“There was so much resistance — from historians, politicians and even the people — that I was ready to hand over the fight to the next generation,” Ms. Taubira said by phone from French Guiana, her voice rising above the din of a tropical rainstorm. “But after nine years of battle, we won.”

A scale model of a sugar plantation in the colony of St.-Domingue, circa 1774, at the Museum d’Aquitaine. Credit: Andrea Mantovani for The New York Times

In 2012, the airport was renamed after Félix Éboué, a descendant of enslaved people who in 1936 was appointed the governor of Guadeloupe, then a French colony in the Caribbean.

The enduring ties between France and its former colonies also continue to shape the perspective of Francophone Africans, generations after independence.

Poor, young African migrants keep risking their lives to cross the Sahara and the Mediterranean, homing in on France and its vague, though talismanic, pull.

The elite keep apartments in Paris and send their children to schools there.

Mr. Diallo, the Senegalese-born activist in Bordeaux, left Africa a quarter-century ago as a young man imbued with the words of Léopold Senghor and Aimé Césaire. In France, he built a life at the bend in the river, making its town his, too.

“The desire for Europe is stronger than the desire for Africa,” Mr. Diallo said. “Even in us, it’s not at all absent. We came to study here and finally we stayed. We became French.”

A square named for the Haitian hero Toussaint Louverture features a bust by the Haitian artist Ludovic Booz and an explanation of Bordeaux’s role in the slave trade. Credit: Andrea Mantovani for The New York Times

This article was orignally published by The New York Times.

Norimitsu Onishi is a foreign correspondent on the International Desk, covering France out of the Paris bureau. He previously served as bureau chief for The Times in Johannesburg, Jakarta, Tokyo and Abidjan, Ivory Coast.