By Donald Yacovone —

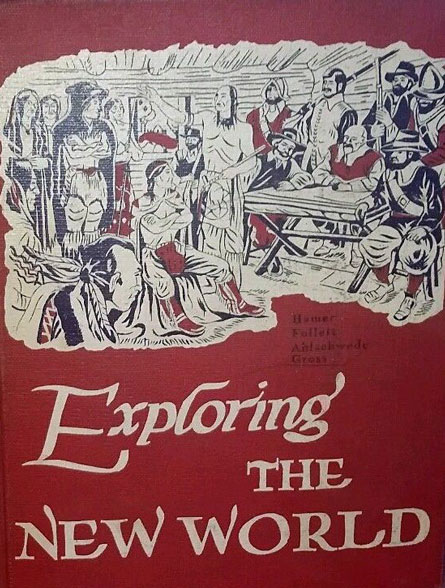

There it sat on a library cart with fifty other elementary, grammar, and high school history textbooks, its bright red spine reaching out through time and space. As I opened the book’s crisp white pages, it all came back. My loud gasp aroused those near me at the Special Collections Department of Harvard University’s Monroe C. Gutman Library. Exploring the New World, by O. Stuart Hamer, Dwight W. Follett, Benjamin F. Ahlschwede, and Herbert H. Gross — published repeatedly between 1953 and 1965 — had been assigned in my fifth grade social studies class in Saratoga, California.

I began research in textbooks as part of a broader study of the legacy of the antislavery movement. My project, The Liberator’s Legacy: Memory, Abolitionism, and the Struggle for Civil Rights, 1865–1965, aims at assessing the impact of William Lloyd Garrison and his antislavery colleagues, both black and white. I wished to look at how the Garrison children and grandchildren; the founders of the NAACP like Mary White Ovington, Moorfield Storey, and W.E.B. Du Bois; John Jay Chapman; and William Monroe Trotter and the Boston African American community depended upon and employed the legacy of the antislavery movement to create the modern civil rights movement. As part of that project, I wanted to determine how abolitionism had been presented in our school textbooks. I imagined a quick look and then a deep plunge back into a series of manuscript collections for The Liberator’s Legacy. Instead, I found myself immersed in the Gutman Library’s invaluable collection of nearly three thousand U.S. history textbooks, dating from about 1800 to the 1980s. Unintentionally, I am now engaged in a study of how abolitionism, race, slavery, and the Civil War and Reconstruction have been taught in our nation’s school books from the 1830s to the present. This new project, Teaching White Supremacy: The Battle Over Race in American History Textbooks, for me is offering almost daily revelations.

I began research in textbooks as part of a broader study of the legacy of the antislavery movement. My project, The Liberator’s Legacy: Memory, Abolitionism, and the Struggle for Civil Rights, 1865–1965, aims at assessing the impact of William Lloyd Garrison and his antislavery colleagues, both black and white. I wished to look at how the Garrison children and grandchildren; the founders of the NAACP like Mary White Ovington, Moorfield Storey, and W.E.B. Du Bois; John Jay Chapman; and William Monroe Trotter and the Boston African American community depended upon and employed the legacy of the antislavery movement to create the modern civil rights movement. As part of that project, I wanted to determine how abolitionism had been presented in our school textbooks. I imagined a quick look and then a deep plunge back into a series of manuscript collections for The Liberator’s Legacy. Instead, I found myself immersed in the Gutman Library’s invaluable collection of nearly three thousand U.S. history textbooks, dating from about 1800 to the 1980s. Unintentionally, I am now engaged in a study of how abolitionism, race, slavery, and the Civil War and Reconstruction have been taught in our nation’s school books from the 1830s to the present. This new project, Teaching White Supremacy: The Battle Over Race in American History Textbooks, for me is offering almost daily revelations.

After reviewing my first fifty or so textbooks, one morning I realized precisely what I was seeing, what instruction, and what priorities were leaping from the pages into the brains of the children compelled to read them: White Supremacy. One text even began with the capitalized title: “The White Man’s History.” Across time and with precious few exceptions African Americans in these books appeared only as a problem, only as “ignorant negroes,” as slaves, and as anonymous abstractions that only posed “problems” for the real subjects of this written history: white people of European descent. The assumptions of white priority and white domination suffuse every chapter and every theme of the thousands of textbooks that have blanketed the schools of our country. This vast tectonic plate still underlies American culture and we ignore it at our peril. While the worst features of our textbook legacy have ended, as the recently published study (2018) by the Southern Poverty Law Center, Teaching Hard History: American Slavery shows, our schools are still ignoring the difficult issues raised by our past, and the themes, facts, and attitudes of supremacist ideologies remain embedded in our national identity, in what we teach, and in what we learn.

Historians may occasionally bemoan their lack of influence, but as my appraisal of our nation’s textbooks revealed, historians of the twentieth century exerted an enormous impact on the way modern Americans have come to understand their history. The results are painfully evident and their work either got filtered down into the schoolbooks as interpreted by educators, professors of education, and school administrators, and sometimes through popular authors, or was directly transmitted by preeminent Ph.D.-trained scholars. The results of that considerable influence we can see today in cities and towns from Charlottesville and Richmond, Virginia, to Berkeley, California. To appreciate why white supremacy remains such an integral part of current American society, we need to appreciate how much it suffused our teaching from the outset.

Noah Webster’s History of the United States (1832), unexpectedly published in Louisville, Kentucky, is distressingly typical of most U.S. history textbooks published before the Civil War. The Connecticut-born Webster of dictionary fame once told the black minister and abolitionist leader Amos G. Beman that “wooly haired Africans” have “no history, & there can be none.” To Beman, Webster dismissed Africans as nonentities and in his book he elevated puritans, especially Connecticut puritans, to the level of founding fathers. His History made only passing mention of colonies (later states) below Mason-Dixon and completely ignored slavery. History, for Webster, was the record of his puritan forebearers, and no others. The standard of whiteness-in-history had been set.

Until 1860, no American history textbook ever mentioned the name of an abolitionist or even the existence of an antislavery movement. If slavery was mentioned at all, the discussion focused on Congress and on political leaders like Henry Clay. History, for these authors, took place in European exploration, colonization, Revolution, Constitution-forming, party politics, and in successive presidential administrations — and nowhere else. The Connecticut-born Samuel Griswold Goodrich, who famously also wrote as “Peter Parley,” became one of the most successful textbook authors and writers of the mid-nineteenth century. He claimed to have published 170 different volumes, selling 7 million copies. He also boasted that his Pictorial History of the United States, originally published in 1843 (also in Louisville) and still in print after the Civil War, sold 500,000 copies. His 1866 edition, published after Goodrich’s death in 1860, simply tacked on a new chapter about the war to the older edition, but neglected to discuss the fall of slavery. Thus, the message to students: black lives do not matter.

There are exceptions to these generalizations, of course, and I intend to focus on them in my book. Still, textbooks published occasionally in the 1870s and into the early 1900s, such as ones by Thomas Wentworth Higginson, the abolitionist and colonel of the First South Carolina Volunteers; by the Canadian-born author, newspaper editor, and librarian, Josephus Nelson Larned; and the famed Civil War reporter Charles Carleton Coffin; or after 1900 by the Harvard University historian, Albert Bushnell Hart, treat the abolitionist movement with unusual sympathy. They saw it as an agent of democratic change and depicted its membership as unpopular Cassandra’s, but as men and women who stood up to slavery and created the constituencies that Lincoln and his fellow Republican politicians used to resist the South. Despite the era and the limitations of available resources, these authors presented history more fully and inclusively than any other, even giving space to Frederick Douglass, Harriet Tubman, and Sojourner Truth.

The hundreds upon hundreds of other textbooks, however, some even providing sympathetic views of the abolitionists and even treating John Brown dispassionately, revealed the authors’ real themes and prejudices when dealing with the history of Reconstruction. Whatever these authors felt about the desirability of ending slavery, when it came to the years following the Civil War all the sacrifice and best intentions came to naught. Inevitably the worst chapter of almost every textbook published before the 1960s, textbook authors repeated relentlessly and emphatically the phrase “ignorant negroes” to describe the freed people who struggled to find a future amid the embattled landscape and intractable resistance of Southern whites. Indeed, reading our textbook history of Reconstruction from about 1900 to the mid-1960s is a stunning immersion in white arrogance, black incapacity, and nostalgia for the sweet days of slavery and Southern white racial domination.

Arthur C. Perry and Gertrude A. Price, American History, 2 vols. (New York: American Book Company, 1914), 135.

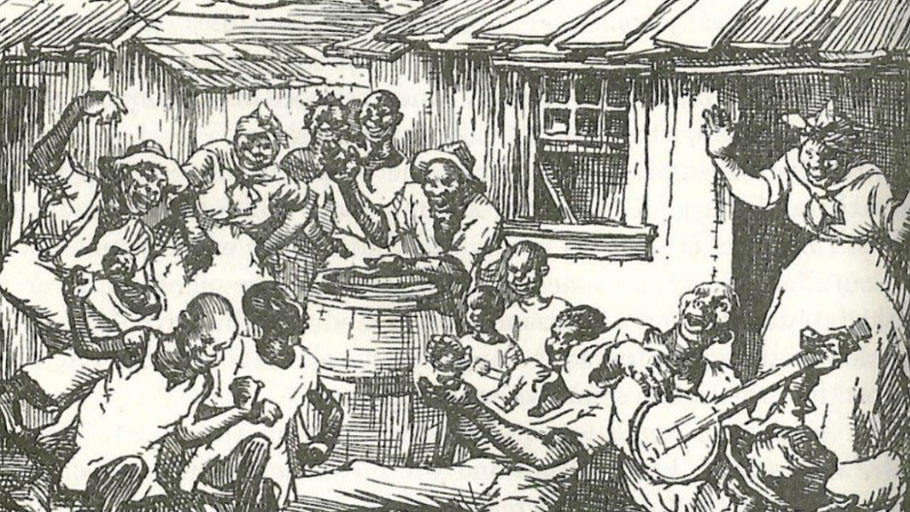

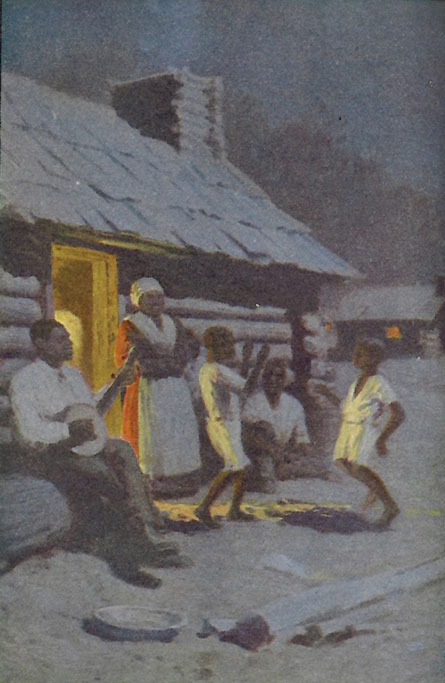

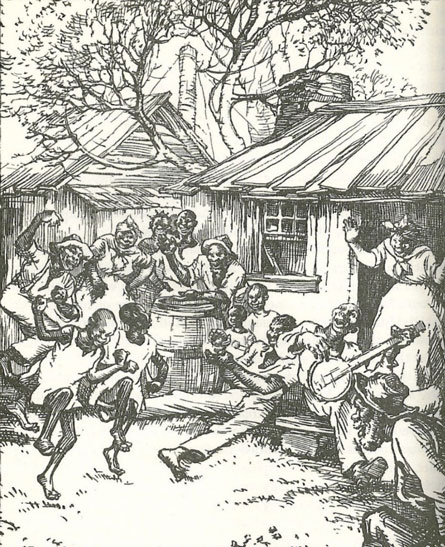

Arthur C. Perry and Gertrude A. Price’s two volume American History, a grammar school text, helped explain the life of slaves by employing an image of gleeful “negroes” at their cabin’s door after a day’s work, enjoying getting “together for a rollicking time.” Students would be inculcated with the notion that African American slaves lived in serene contentment, loved their masters, and displayed their inherent inferiority by the language and images employed by writers like Fremont P. Wirth, a professor at Nashville’s famed Peabody College for Teachers. His textbook, The Development of America, first published in 1937, remained in print until 1957 influencing generations of young minds.

“Slaves at home, after the day’s work was over. Negroes always have been fond of singing and dancing; and the banjo has been a favorite musical instrument with them.” (Drawing by Hanson Booth) in Fremont P. Wirth, The Development of America (Boston, New York, Atlanta: American Book Company, 1937), 352.

But for generations of students, the innumerable textbooks of the Massachusetts-born, Columbia University historian David Saville Muzzey (1870–1965) shaped their understanding of the central crisis of American history. With over fifty publications, his influence became pervasive, especially through his History of the American People, a heavily illustrated tome of 700 pages for high school students, used relentlessly between 1927 and 1938, and then for many decades after under various other titles. For Muzzey, “the mutual provocation of the abolitionists and the ardent defenders of the slavery system” (275–77) caused the Civil War, and the North bore prime responsibility for causing the South to secede because of its relentless hostility to slavery. Moreover, whatever benefits the nation might have derived from freedom, Muzzey explained, became nullified by the unmitigated disaster of Reconstruction. According to Muzzey’s popular text, it set the untutored former slaves against “the only people who could really help them . . . their old masters.” Instead of peace, comity, and justice for Southern whites, Northern radicals manufactured an “orgy of extravagance, fraud, and disgusting incompetence.” Most egregiously, they placed upon the South the “unbearable burden of negro rule.” This “crime of Reconstruction,” he wrote, would be the root cause of sectional bitterness that would endure “to the present day.” (402–22)

Building on decades of scholarship scorning the Reconstruction Era, especially that of William A. Dunning and Claude Bowers, the textbook by Gertrude Van Duyn Southworth and John Van Duyn Southworth, The Story of Our America, proved popular and was adopted by the state of Indiana for the 7th and 8th grades. The authors, a junior college instructor and a prep school teacher, followed the Muzzey line and rehearsed the usual litany of abuses caused by Carpetbaggers, Scalawags, and their “Negro” tools, and explained that the South eventually achieved justice and white rule through informal organizations of Civil War veterans who could not sit idly by and watch Yankees, Negroes, and their Southern conspirators pillage Southern treasuries and threaten white women. The text employed this image of white-robed, galloping Klansmen, borrowed from the 1915 film Birth of a Nation, to illustrate how the Klan and similar groups defeated corrupt Carpetbag and Scalawag governments and restored respectable whites to their justly dominant position.

Gertrude Van Duyn Southworth and John Van Duyn Southworth, The Story of Our America (New York: Iroquois publishing Co., 1951), 351

And this text was published in 1951. While ending slavery was usually rendered in most textbooks as a glorious accomplishment, it all came crashing down when intolerant and aggressive Radical Republicans seized control of Washington in a coup and forced black enfranchisement upon a prostrate South. Almost without exception the vast army of textbooks published before the 1960s instilled in generations of young American students a version of history no different than that found in Thomas Dixon Jr.’s The Leopard’s Spots(1902) or The Clansman (1905), and usually not as well written.

Authors more familiar to current scholars and historians, such as Marcus Jernegan, Merle Curti, Ralph Henry Gabriel, Ralph Volney Harlow, and John D. Hicks, leading historians of their time, also crafted textbooks for junior high and high schools. Between 1931 and 1943, the Yale intellectual historian Ralph Henry Gabriel, along with Mabel B. Casner, a Connecticut high school teacher (the teacher of the late Massachusetts congressman Gerry Studds), explained to students that the central problem of Reconstruction was that the former slaves “found that freedom could be a greater curse than slavery.” In Southern states under Republican rule, the “Negroes were ignorant, and most of the carpetbaggers were rascals.” Fortunately, however, white men organized secret societies to “fight the evils that surrounded them,” especially theft, which was “very common among those who had recently been slaves” and restored white power. (Exploring American History, 501–05). The University of Chicago’s Marcus Jernegan’s The Growth of the American People(1934) relied on the racially poisonous scholarship of Claude Bowers, George Fort Milton, and even the novels of Thomas Dixon, Jr. He described the Freedmen’s Bureau as an organ for “race hatred,” but the Ku Klux Klan appeared as the honest bulwark against Carpetbag corruption. According to Jernegan, the Klan did little more than play on the “superstitious fears of the negroes” and scared them at night by dressing in white sheets and shouting “Beware! The Great Cyclops is angry!” and thus discouraged blacks from voting. Accusations of real Klan violence, he asserted, were largely fabricated by Carpetbaggers and Scalawags. (543–44, 550)

The University of California’s John D. Hicks, best known for his study of the Populist Movement, described slavery in his advanced textbook, A Short History of American Democracy (1943) as “By and large . . . a distinct advance over the lot that would have befallen him [the slave] had he remained in Africa.” Besides, he remarked, where else could a people so untutored enjoy picnics, barbecues, singing, and dancing? The slaves’ “devotions [religion] were extremely picturesque, and their moral standards sufficiently latitudarian to meet the needs of a really primitive people. Heaven to the Negro was a place of rest from all labor, the fitting reward of a servant who obeyed his master and loved the Lord. . . . [C]ohabitation without marriage was regarded as perfectly normal, and a certain amount of promiscuity was taken for granted. Slave women rarely resisted the advances of white men, as their numerous mulatto progeny abundantly attested.” (291–92).

Berkeley’s history department recalls Hicks’s enormous influence, classes with over 500 students, and the impossibility of estimating “the number of students whose knowledge of American history has been built on the Hicks histories, but it is certainly an immense number.” (May T. Morrison, www.cdlib.org) That such rabid fiction could pass for history in 1943, or at any other time, still leaves me reeling. But this kind of textbook “history” continued, largely ignoring the work of prodigious African American scholars like John Wesley Cromwell, George Washington Williams, Carter G. Woodson, and W.E.B. Du Bois, until the 1960s when new generations of black and white scholars began transforming our understanding of the American past, and the place of race in it.

And what of Exploring the New World, my fifth grade textbook? Its painfully simplistic story never mentioned any abolitionists or even an antislavery movement. Slaves, on the other hand, proved necessary to pick cotton — “Who else would do the work?” the authors asked. Yet, people of the North did not believe that men and women “should be bought and sold.” (261–62). In the end, the book took a reconciliationist approach to slavery and the Civil War, asserting that everyone (white) was brave, everyone (white) fought for principle, and Robert E. Lee represented all that is noble, gallant, and heroic in American society. “His name is now loved and respected in both North and South. We know that he was not only a gallant Southern hero but a great American.” (264–67) While I never forgot the book, fortunately, its lessons made few lasting impressions upon me. I fear, however, that we cannot say the same for many of our fellow citizens’ experiences with American history in our public schools, as the outbursts of anti-Semitism and racism over the past year appear to affirm.

Donald Yacovone is an Associate at the Hutchins Center for African and African American Research at Harvard University.