By Brandy Monk-Payton, Public Books —

I. CHANNELING FREEDOM DREAMS

A Black boy presses his forehead and cheek against the television. He shuts his eyes, clasps his hands together, and mutters fervently. It is a scene from “The Big Tall Wish,” a Season 1 episode of The Twilight Zone. The episode, which was released in 1960, follows Bolie Jackson (Ivan Dixon), a washed-up prizefighter who has lost all confidence in his athletic capabilities.

Henry Temple (Steven Perry), who is a fan and friend of Bolie, intently watches the latter’s comeback boxing match live, on the TV set at home with his mother. As Bolie gets beaten—and is sure to be knocked out and lose—Henry wishes for him to win. Henry makes the “biggest, tallest wish” by embracing the screen, with his reflection showing in its glow. And then, in an instant, Bolie has magically traded places with his opponent and become the champion.

Henry’s supernatural encounter with the TV set prompts me to contemplate the potential of Black folks to call into being, through the melding of gaze and touch, an alternative tele-vision—another way of relating to the small screen that prompts a shift in consciousness and generates an other-world.

I think about it now, as the United States broadcasts images of protests against police violence spurred by the deaths of George Floyd, Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor, Tony McDade, and too many more to name here. In the midst of deep-rooted cynicism, nihilism, and pessimism concerning the pervasiveness of anti-Blackness, there is something poignant about watching Henry’s affective engagement with television and the promise of transformative change via transmission.

“The Big Tall Wish” is not about the horrors of police brutality. Though The Twilight Zone makes use of allegory to infuse its science-fiction and fantasy tales with social and political commentary, this episode’s message is simple: miracles can happen.

But race is central to the story, Lewis Gordon writes, even though not made explicit (save for the all-Black principal cast). The episode, Gordon notes, implicitly “offered an intergenerational question between the adult fighters of the civil rights struggle and the generation for whom they fought.”1

One can picture the violence, both symbolic and material, that Bolie has experienced in his lifetime: brawling with other boxers, but also contending with racial discrimination and oppression. He is certainly tired and hardened by the world. He has many visible scars. Above all else, Bolie is scared. In contrast, Henry is unwaveringly optimistic. The young boy utilizes the force of his imagination—through TV—to create a different reality, one in which freedom dreams come true.

“Don’t you be afraid, Bolie. Understand? Don’t you be afraid.”

II. THE REVOLUTION WILL (NOT) BE TELEVISED?

Television’s communicative capacities are indebted to Black freedom struggles. The civil rights movement is integral to US television’s understanding of itself as a mass medium that promotes the ability to bring events to viewers live from the scene. It became crucial for TV to directly present Black American expressions of what Sasha Torres describes as “physical suffering and political demand” on the ground, in the fight for civic inclusion.2

In 1965, Martin Luther King Jr. addressed a rally the day after peaceful marching in Montgomery, Alabama, had resulted in police attacks on activists, which included the beating of a university student. King stated: “We are here to say to the white men that we no longer will let them use clubs on us in the dark corners. We’re going to make them do it in the glaring light of television” (emphasis my own). This oft-circulated quote—on the importance of the public exposure afforded by the TV camera—demonstrates how African Americans recognized the semiotics of protest and its moral implications. If, that is, the protests were broadcast on television news to white liberal audiences.

But, as Aniko Bodroghkozy has documented, establishing a national consensus on the immorality of prejudice, bigotry, and racism was difficult to achieve, even in the classic network system of the 1950s–1970s.3 Despite legal and political gains from the civil rights movement—and one should note that the Voting Rights Act of 1965 is currently being dismantled by the Supreme Court—racial conflict and antagonism persisted. Soon, “the revolution will not be televised” became the rallying cry of Black radicals, buoyed by poet Gil Scott-Heron’s song of the same name. The lyrics suggest that TV shows and commercials would not capture societal transformation.

What do we want and need from Television right now? What are the limitations and possibilities of the medium in addressing and redressing anti-black violence?

Yet, during the Black Power era, as incisive scholarship from Christine Acham and Devorah Heitner has detailed, social change did sometimes manifest in mainstream and public affairs programming.4 In contrast, the conservatism of the Reagan years, which has been examined by Herman Gray, ushered in representations of African American upward mobility and the achievement of the American Dream—at the same time as poor and working-class Blackness became pathologized in the news.5 The work of television, as a cultural form and as a technology, shifts across sociohistorical climates of Black life under subjugation.

Take, for example, a remark by a student interviewed for the Communist newspaper Revolutionary Worker in 1992, after the acquittal of police officers charged with the physical assault of Rodney King, which was caught on tape. “Somebody brought a video to school—the video of Rodney King—and then somebody put it on the television and then everybody just started to break windows and everything. Then some people got so mad they broke the television.” Elizabeth Alexander argues that “the body has a language which ‘speaks’ what it has witnessed.”6 As I have discussed elsewhere, this actual scene of spectatorship that the student describes—in contrast to the spectatorship of the fictional Henry of The Twilight Zone—attests to how television can become a volatile apparatus in its transmission of racial violence.

News and entertainment programming grappled with the Los Angeles rebellion in the early ’90s and, since then, we have continually returned to that formative moment. With the rise of Black Lives Matter (BLM), we have tried again to make sense of TV’s representational logics, first during the 2014 uprisings in Ferguson, Missouri, after Michael Brown’s murder, and then in 2015 after the killing of Freddie Gray, in Baltimore, Maryland.

Five years later, entering a new decade, it is not only the citizens of Minneapolis, Minnesota, who can be seen protesting on our multiple screens. Now, with the advent of even more online social-networking platforms, traditional television is but one form of mediation that shows the entire nation enveloped in turmoil connected to state violence.

In the midst of my own anger, frustration, and nervous anticipation, I find myself asking: What do we want and need from television right now? What are the limitations and possibilities of the medium in addressing and redressing anti-Black violence?

Television audiences have increasingly fragmented, due, in large part, to a move toward narrowcasting that began in the late 1970s. This fragmentation exacerbates the lack of a united front on the state of race relations (one need only look at the contrast in the protest coverage of MSNBC and Fox News).

The television industry is now trying to come together as one voice for cultural change. In the past several weeks, networks and streaming platforms have released statements expressing solidarity with Black employees, creatives, and viewers, in the fight against racial injustice. The corporate responses posted on social media pages are spelled out in white, sans serif letters against a black background. All follow much the same script. HBO quoted James Baldwin. The landing page for Amazon Prime Video tells me that “Black lives matter” and provides a list of film and television content that centers “Black History, Hardship, and Hope.” I suppose I should appreciate the alliteration. While the popular discourse on BLM has demonstrably shifted since 2014, it is hard not to read these corporate gestures as cynical branding to retain the “woke” millennial demographic.

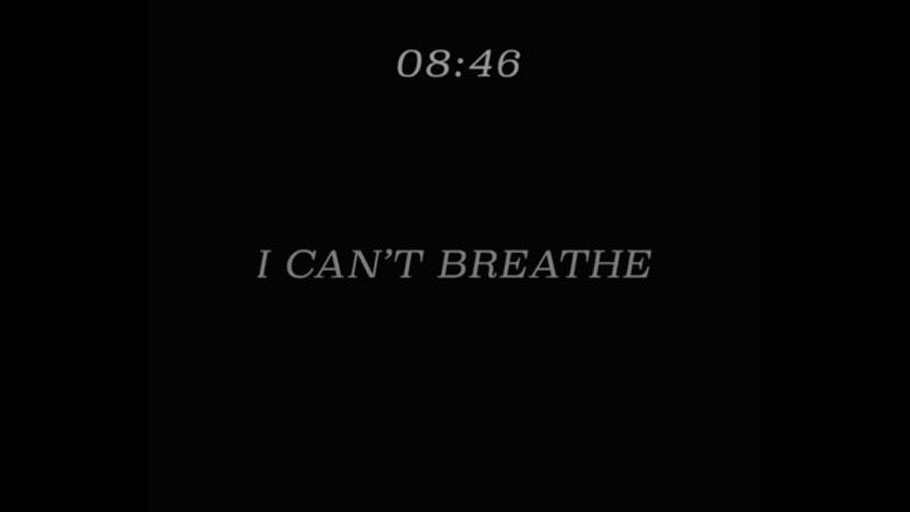

In an unprecedented move that went beyond a statement, ViacomCBS—partnering with the nonprofit advocacy organization Color of Change—went dark on its cable channels targeted toward children, teens, and young people on June 1 at 5 p.m. for eight minutes and 46 seconds. This period of time marks the duration for which white police officer Derek Chauvin pressed his knee into the neck of George Floyd, stifling his respiratory pathways and killing him. A clock counted down at the top of the black screen, as the words “I CAN’T BREATHE” pulsated in italics beneath it. Viewers heard audio of someone breathing, the inhales and exhales in sync with the bolding and receding of the text.

Some concerned parents disapproved of this interruption of regularly scheduled programming on Nickelodeon, stating that it terrified their kids (ironic, given the terrorizing of Black communities over centuries, including children like Aiyana Stanley-Jones and Tamir Rice, both of whom were murdered by police).

I watched this solemn televisual tribute to Floyd on MTV, sandwiched between two episodes of Ridiculousness, the half-hour gag show that consists of silly viral videos from the internet. When the tribute was over, I could barely blink before a Pop Tart commercial splashed onto the screen, the bright blue promo visually jarring after the darkness of the tribute. While the latter urged viewers “to take real action,” the mandate of TV flow—to bring audiences to advertisers—meant that this “real action” seemed to be the consumption of goods (frosted toaster pastries!). Television cannot stop selling things, so it sells Black death in the guise of support for the cause.

Perhaps I am being too critical of the blackout. As a visual provocation, it commanded attention and a visceral reaction—though I was left wondering who the audience of such a display is. Television industry silence may very well be complicity, but complicity also looks like ViacomCBS still providing a platform to BLM critic Bill O’Reilly through Pluto TV online. As large protests continued in Los Angeles, law enforcement actually used CBS’s former LA headquarters as a staging ground before striking nearby protesters with batons. Laid bare are the contradictions in American television’s desire to be relevant, to matter in this moment (“Black storytelling matters,” Netflix tweets), to be part of the revolution.

To be part of the revolution requires a reckoning with the status quo. Since footage of excessive force against those who have died in police custody or protested on the streets has circulated, there have been many impassioned critiques of cop shows and calls to halt production on these programs.

Indeed, as Donald Trump shouts for “LAW & ORDER” on his Twitter feed, one can’t help but think of the Dick Wolf police procedural franchise, a staple of network television since 1990. Law & Order: SVU star Mariska Hargitay replied to Trump on Twitter (“You mean tyranny and racism!”), though one should not easily forget “American Tragedy,” SVU’s 2013 episode that clumsily depicted BLM activism (via the Paula Deen racism scandal, no less). With the long-running Cops reality series now canceled, legacy media must confront its portrayals of criminality and law enforcement to reform storytelling around race and policing.

Laid Bare are the contradictions in American television’s desire to be relevant, to matter in this moment, to be part of the revolution

It would be impossible to think about television’s engagement with state-sanctioned anti-Blackness without touching on Watchmen. It feels like an eternity since the acclaimed series premiered on HBO, less than a year ago. While the show is based on the DC Comics series of the same name, its creator Damon Lindelof revealed that he was also inspired by Ta-Nehisi Coates’s award-winning essay “The Case for Reparations.” The series begins with the violent destruction of what was known as Black Wall Street in Tulsa, Oklahoma, by a white mob, in 1921.

Watchmen is a complex show that centers cops and, specifically, the perspective of Black police officers Angela Abar (a.k.a. Sister Night, played by Regina King) and Will Reeves (played in older and younger versions by Louis Gossett Jr. and Jovan Adepo, respectively). The show’s apologia for law enforcement (and US empire) has been commented on extensively.

I rewatched all nine episodes this past week, before HBO made the series available to view for free between June 19–21, ostensibly in honor of Juneteenth, which commemorates the day, in 1865, when enslaved Black people in Galveston, Texas, heard of their emancipation.

Watchmen hinges its narrative on historical and contemporary Black experience, and I was struck by what still resonates for me: how the series makes meaning through its stunning visual style and the nuanced narrative routed through Black female speculative pleasure. Yet, though the program indulges in many different kinds of fabulation, there is a valid criticism to be made of its simultaneous compulsion to reenact the historical Tulsa massacre and deploy what Leslie Lee calls “real black trauma” and “real black pain” as spectacle. The show feels a responsibility, per Lindelof, to foreground race in this cultural atmosphere, but perhaps overcompensates in form and content for its inability to engage fully with the conditions of anti-Blackness.

There is a connection, here, between psychic compensation and the political concept of reparation. Watchmen narrativizes the latter (known as “Redfordations” on the show) as tax breaks to victims of racial injustice and their direct descendants. But despite this show’s fictional commitment to such support, real-life racial violence—and the subsequent protests around the country and globe—have brought into sharp relief that television, as a medium, is fundamentally ambivalent in its commitment to the redress of Black loss, suffering, and injury in the afterlife of slavery.

III. TELE-VISIONARY

As many of us now find television failing to live up to the gravity of the moment, there are lines of flight that propel us to think more dynamically about what Black folks can do with the medium, beside and beyond representation. I don’t remember exactly how I came to discover Marion Stokes, an African American woman who is the subject of Matt Wolf’s 2019 documentary Recorder: The Marion Stokes Project. Stokes secretly taped 70,000 hours of TV news every day for over 30 years. Though she died in 2012, at the age of 83, her legacy lives on in this archive of programming.

Stokes is an exemplar of Black women’s critical creative capacities to engage with television. Innately perceptive about the significance of TV flow, immediacy, and presence, her material practice of recording strove to produce new knowledges that could combat the broadcast of misinformation and disinformation. Stokes was a former Communist, a civil rights organizer, a librarian, and a producer of a local news show in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. These experiences gave her the tools and techniques to contest dominant media agendas. Stokes watched and taped in the service of her wish that, one day, her archival experiment would be able to help the public discern patterns and cycles in news coverage and, ideally, activate audiences to seek the truth about the world.

I still hear Henry’s call into the television screen in The Twilight Zone: “If you don’t believe, Bolie, it won’t be true … You’ve got to believe.”

Marion Stokes believed in the power of television. I like to imagine that she would be recording this current moment of righteous unrest with satellite feeds from all over the world. She had faith in the medium: that something else might emerge from the transmission, and that new social and political frontiers could be realized. When you can see at a distance in the present—when you become a tele-visionary—maybe, like Henry, you can alter the future.

Notes

- Lewis Gordon, “Through the Twilight Zone of Nonbeing: Two Exemplars of Race in Serling’s Classic Series,” Philosophy in The Twilight Zone, edited by Noël Carroll and Lester H. Hunt (Wiley-Blackwell, 2009), p. 113. ↩

- Sasha Torres, Black, WHI, and in Color: Television and Black Civil Rights (Princeton University Press, 2003), p. 15. ↩

- Aniko Bodroghkozy, Equal Time: Television and the Civil Rights Movement (University of Illinois Press, 2013). ↩

- Christine Acham, Revolution Televised (University of Minnesota Press, 2005); Devorah Heitner, Black Power TV (Duke University Press, 2013). ↩

- Herman Gray, Watching Race: Television and the Struggle for Blackness (University of Minnesota Press, 2004). ↩

- Elizabeth Alexander, “‘Can You Be Black and Look at This?’: Reading the Rodney King Video(s), Public Culture, vol. 7, no. 1 (1994), p. 83. ↩

Source: Public Books

Featured image: Steven Perry as Henry Temple in “The Big Tall Wish,” a Season 1 episode of The Twilight Zone