Fall of Africa’s greatest empire

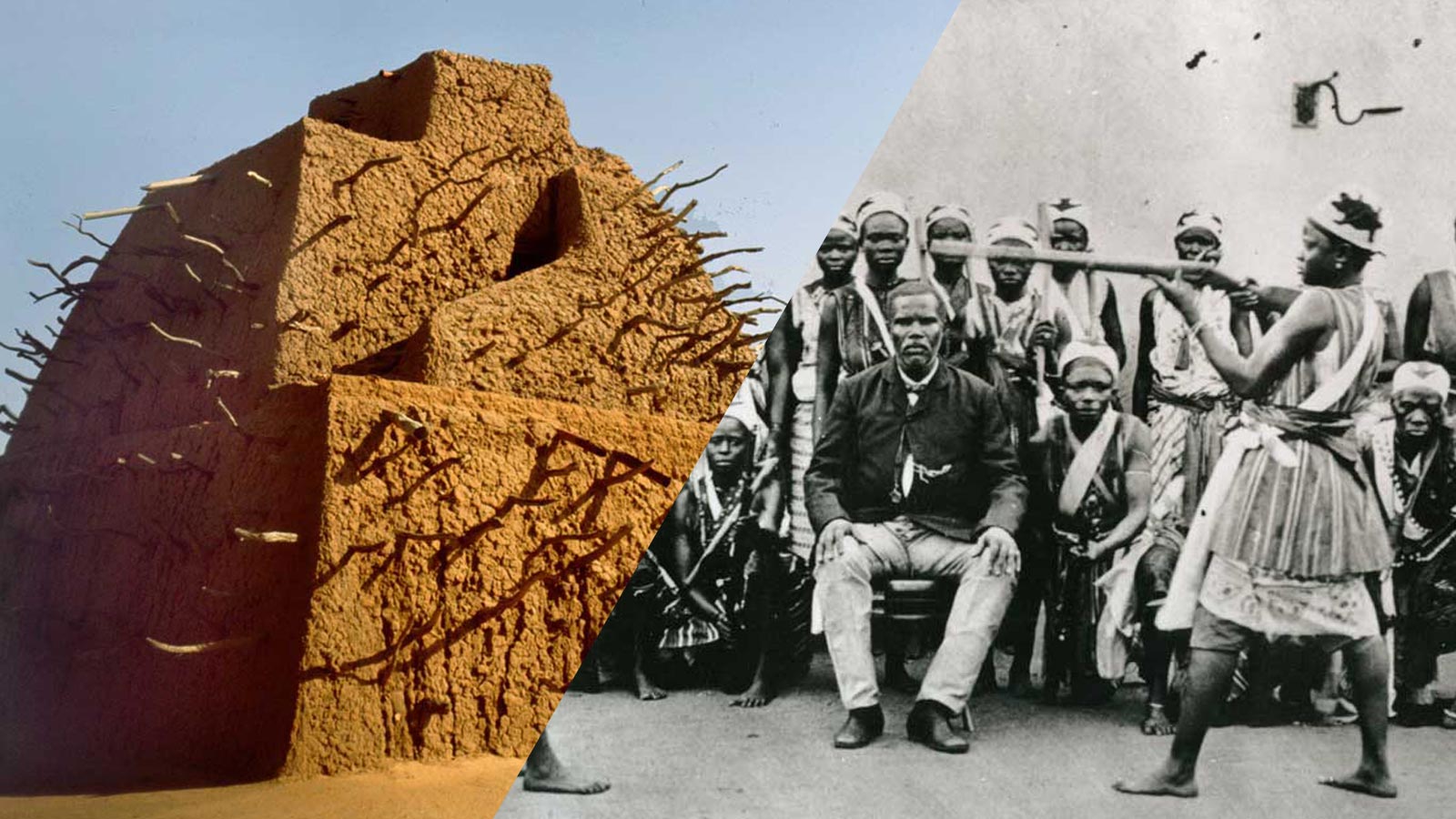

The tomb of Emperor Askia Toure at Gao, Mali (Alamy).

The Battle of Tondibi, which resulted in the defeat of the Songhay army, took place on 13 March 1591.

By Mathew Lyons, History Today —

The Songhay Empire would not be the first military power to set too much store by its cavalry. Founded in 1464 out of the ruins of the Malian Empire, Songhay was the largest of the indigenous empires in Africa. At its zenith, it covered around 540,000 square miles, stretching east-west for 1,200 miles along the River Niger with the Sahara to the north and the Sudan savannah to the south. Although it incorporated the great centre of Islamic learning and culture at Timbuktu, its capital was sited further east at Gao.

Internally, its biggest problem was succession. While some emperors, such as Askia Toure (1493-1528) and Askia Dawud (1549-82), were able to secure their thrones and rule successfully, the succeeding periods were characterised by fratricidal rivalries and rifts.

But it also had a powerful enemy. In January 1590 the Moroccan sultan Al-Mansur sent Emperor Askia Ishaq II an ultimatum. Ishaq sent back spears and horseshoes; a sign that his horsemen would prevail. Besides, if Moscow had its winter to defend it from Napoleon, Songhay had the Sahara. Al-Mansur was undeterred. He had arquebuses and cannon on his side. The Songhay were so disdainful of the new technologies of war it is said that they threw captured Moroccan firearms into the Niger.

The 4,000-strong Moroccan army entered the Sahara in late December, provisioned by 10,000 camels and 1,000 pack horses. Meanwhile, Ishaq’s army – at least 40,000 strong, although possibly more than twice that – was assembled too slowly to attack the invading army as it emerged exhausted from the desert.

These then were the circumstances of the Battle of Tondibi, not far from Gao, which was fought on 13 March 1591 (though some reports suggest it may have been the day before.) One report says that Ishaq’s plan was to break the Moroccan line by driving hundreds of stampeding cattle into it. But, terrified by the noise of the cannon, the cattle turned and crashed into the Songhay army instead. Their ranks scattered; Ishaq himself fled. In the end only a small group of Songhay warriors, who had roped themselves together, were left standing. They fought to the last.

Last stand of Dahomey’s female army

Women of the ahosi guard King Gezo, late 19th century (Archives Charmet/Bridgeman Images)

The women’s army, regarded as superior to its male counterpart, last saw action at Cana on 4 November 1892.

By Mathew Lyons, History Today —

Founded in the 17th century, the West African kingdom of Dahomey was a bellicose, expansionist state. The king’s main duty was to ‘make Dahomey always larger’. King Agaju boasted that, whereas his grandfather had conquered two countries and his father 18, he had conquered 209.

European contact with Dahomey began with the slave trade; the kingdom had a regular supply of slaves thanks to its campaigns. But European visitors in the 1720s were surprised to find the king guarded by women.

Historians disagree about when the women’s palace guard expanded into an army. But by the 19th century witnesses regarded the women’s army, though smaller than its male counterpart, to be superior. Where the men shot muskets from the hip, the women took aim and fired from the shoulder. They were ‘the mainstay of the kingdom’, Richard Burton wrote in 1863.

Fighting women fascinated western visitors, who called them ‘amazons’ – a striking example of people interpreting an unfamiliar culture through the prism of their own. The Dahomeans called them ahosi, a generic term for all the kings’ wives, of whom there were several thousand. But again the term ‘wife’ is misleading. Women in the palace had political and other roles that were the equal of their male counterparts, such as advising at councils and interpreting.

King Gezo (1818-58) told the British: ‘My people are a military people, male and female.’ But there is evidence that when palace officials came to villages to pick young women for the ahosi, families tried to hide them. Until the second half of the 19th century much of Dahomey’s army, male and female, was comprised of former captives; they enjoyed high status, but many remained slaves to the end.

They last saw action at Cana, the final battle of a losing war against the French, on 4 November 1892.

Source prt 1: History Today

Source prt 2: History Today