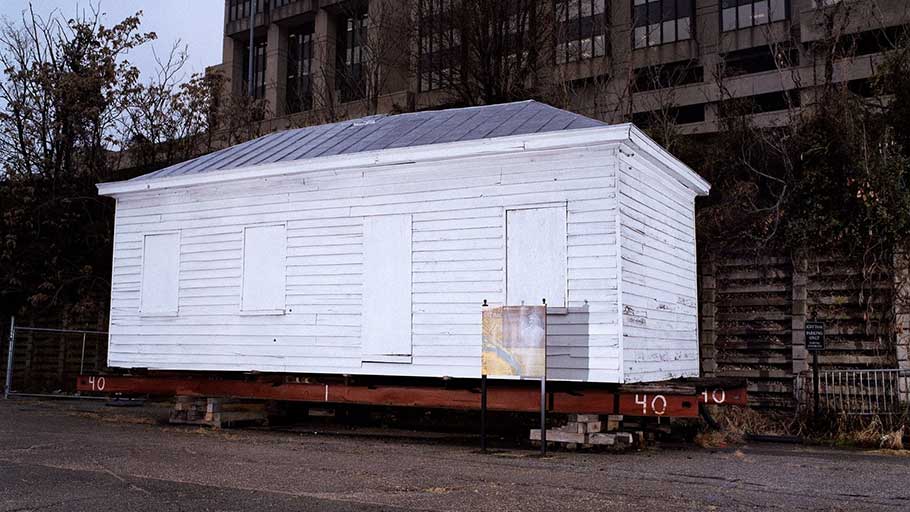

For decades, structures such as Rosenwald schools were deemed insignificant. Photograph by Hannah Price for The New Yorker.

Activists and preservationists are changing the kinds of places that are protected—and what it means to preserve them.

By Casey Cep, The New Yorker —

No one knows what happened to Gabriel’s body. Born into slavery the year his country declared its freedom, he trained as a plantation blacksmith and was hired out to foundries in Richmond, Virginia, where he befriended other enslaved people. Together, they absorbed, from the revolutionary spirit of the era, ideas of independence that were never meant for them. Gabriel kept hammering out whatever his masters demanded, but in secret he began to forge a network of thousands of enslaved and free blacks who planned to rally under a flag stitched with borrowed words: “Death or Liberty.” But a terrible thunderstorm flooded the roads on what was to be the day of their revolt, in August, 1800, and during the delay two of the conspirators betrayed the rest. Within a few weeks, twenty-six of them were hanged. Gabriel was executed less than a mile from the church where Patrick Henry spoke the words that inspired what would have been their battle cry. Some historians believe that Gabriel’s body was left in the burial ground beside the gallows, where it would have joined thousands of other black bodies that, consigned to the bottomland of the city, washed into Shockoe Creek whenever it rained.

Shockoe Bottom, as that valley is known, was the center of Richmond’s slave district. In the three decades before the Civil War, more than three hundred thousand men, women, and children were sold in Richmond, the second-largest slave market in the United States. Not every enslaved person who passed through left the city; many were made to work in its tobacco warehouses, ironworks, and flour mills. Between 1750 and 1816, most of the African-Americans who died in Richmond were interred in what was known as the Burial Ground for Negroes. After that, the graves at Shockoe Bottom were abandoned, and residents claimed more and more of the land for themselves, ignoring the coffins and bones. The city turned what was left into a jail, and then a dog pound; later, state and federal officials carved I-95 through its center.

“I remember thinking there was nothing left,” Brent Leggs told me recently, of his first encounter with Shockoe Bottom. Leggs, the director of the African American Cultural Heritage Action Fund, at the National Trust for Historic Preservation, is typically contacted to help preserve something, even if it is only a crumbling foundation. But in Richmond he was called on to help save what no longer exists.

The first wave of protests began in 2002, when Shockoe Bottom was still a parking lot. Community groups like the Defenders for Freedom, Justice & Equality organized to reclaim the burial ground and memorialize Richmond’s connections to the slave trade. The Defenders held walking tours, educational forums, and vigils at the site. Activists demanded that the city “get your asphalt off our ancestors,” and, although it took a decade, the pavement was eventually cleared. In 2013, the group helped launch another wave of protests after the city proposed building a minor-league baseball stadium at Shockoe Bottom, which would have destroyed what archeological evidence remained and would have desecrated the burial ground. That was when the National Trust stepped in.

A year later, Leggs and his colleagues declared Shockoe Bottom one of America’s most endangered historic places, a designation that the Trust assigns to about a dozen sites annually, fostering public pressure to halt development that would destroy them. The city withdrew its plans for the stadium in 2015; the Defenders then proposed a large memorial park, one that would connect Gabriel’s rebellion with the war that divided the country and also with the one that founded it. For now, the city says that it can’t afford a park of that size, and Shockoe Bottom remains in limbo.

Brent Leggs is the director of the largest-ever campaign to preserve African-American historic sites. Photograph by Hannah Price for The New Yorker.

The struggle over the physical record of slavery and uprising in Richmond is part of a larger, long-overdue national movement to preserve African-American history. Of the more than ninety-five thousand entries on the National Register of Historic Places—the list of sites deemed worthy of preservation by the federal government—only two per cent focus on the experiences of black Americans. Preservationists like Leggs are working with activists, archeologists, and historians to change those numbers. They are fighting to preserve and promote such sites as 1520 Sedgwick Avenue, in the Bronx, known as the apartment building where hip-hop was born; the Pauli Murray Family Home, in Durham, North Carolina, the birthplace of the queer civil-rights lawyer; and Fort Monroe, in Hampton Roads, Virginia, an Army base on the spot where African captives first arrived in this country, in 1619, which became known as Freedom’s Fortress after five hundred thousand slaves emancipated themselves there during the Civil War. One site at a time, Leggs and his colleagues are changing not only what history we preserve but what we think it means to preserve it.

Historic preservation has its own history. The first preservation laws in the United States protected the land itself, beginning with Ulysses S. Grant’s designation of Yellowstone National Park, in 1872. But, with the Civil War barely over, battlefields, cemeteries, and burial sites quickly became a priority for preservation. The passage of the Antiquities Act of 1906 gave Presidents the right to create national monuments, and that meant that they could protect both the terrain and the artifacts of indigenous cultures found there.

Ten years later, the creation of the National Park Service (N.P.S.) granted federal lawmakers more power “to conserve the scenery and the natural and historic objects and wild life therein.” In subsequent years, the category of “historic objects” broadened, and the N.P.S. got involved in preservation efforts at places like Jamestown; eventually, the agency set national policies for surveying historic and archeological sites, protecting significant properties, and erecting historical markers. In 1949, Harry Truman signed legislation creating the National Trust, and in 1966 Lyndon B. Johnson signed the National Historic Preservation Act (N.H.P.A.), which, among other things, established the National Register of Historic Places and the standards of the National Historic Landmarks Program, provided federal funding for the National Trust, and opened preservation offices in all fifty states.

Since its founding, the N.H.P.A. has identified nearly two million locations worthy of preservation and has engaged tens of millions of Americans in the work of doing so. It has helped to generate an estimated two million jobs and more than a hundred billion dollars in private investments. But, because many biases were written into the criteria that determine how sites are selected, those benefits have gone mostly to white Americans. One of the criteria for preservation is architectural significance, meaning that modest buildings like slave cabins and tenement houses were long excluded from consideration. By the time preservationists took notice of structures like those, many lacked the physical integrity to merit protection. Destruction abetted decay, and some historically black neighborhoods were actively erased—deliberately targeted by arson in the years after Reconstruction or displaced in later decades by highway construction, gentrification, and urban renewal.

While state and federal institutions were largely neglecting these areas, communities of color began protecting them on their own. Leggs dates the formal beginning of African-American historic preservation to 1917, when the National Association of Colored Women organized a campaign to pay off the mortgage on Cedar Hill, a Gothic Revival house in Washington, D.C., that had belonged to Frederick Douglass. “Even when it wasn’t called ‘preservation,’ this work was already happening,” Leggs told me on a visit to Cedar Hill in December. The estate sits high above the neighborhood of Anacostia, offering a clear view of the Capitol and the Washington Monument. Leggs, who is forty-seven, bounded up the hundred brick steps from the visitors’ center to the house as though it were his first time there, eager to show me Douglass’s bookshelves and writing desk, his portraits of Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony, the table where he dined with Harriet Tubman and Ida B. Wells-Barnett. “It’s a tangible way of learning about his life, of interacting with all that he accomplished,” Leggs said of the site, which is now managed by the N.P.S. We talked about the dumbbells in Douglass’s bedroom, and how he liked to lift weights; Leggs, who is roughly the same height as the six-foot-tall abolitionist, wondered why the bed was so short (a question apparently asked at historic sites around the world).

Five decades after the National Association of Colored Women rallied to save Cedar Hill, another group of black women worked to salvage what remained of Weeksville, an antebellum free-black community in Brooklyn that was started by the longshoreman James Weeks, in the early nineteenth century. These activists were led by the artist Joan Maynard, who argued that black history needed the same protections as black lives, and that the imperilment of the two was related. “We’ve got to make sure our kids know how they got here, and what those who came before did to try and make a better life,” she said. It was her hope that the homeownership, urban farming, and commitment to liberty of Weeksville’s earliest residents might inspire future ones. Through those efforts, four houses from the original Weeksville settlement were added to the National Register by 1972.

Around the same time, three men in a historically black neighborhood in New Orleans founded a community-improvement group, which led to the formation of the Treme Historic District, where Creole cottages and shotgun residences testify to generations of black life. Five years later, in Florida, the writer Alice Walker found the lost burial site of Zora Neale Hurston, and set in motion a revival of Hurston’s historically black incorporated home town of Eatonville, which was added to the National Register in 1998. That discovery also renewed interest in Hurston’s writing; her books were reprinted and elevated to the literary canon. Historic preservation and artistic renaissance often go hand in hand: in Congo Square, the area of Treme where enslaved people gathered to drum and dance, contemporary musicians honor that history by continuing to perform in what is now known as Louis Armstrong Park.

Eventually, the federal government caught up with the work of descendant communities, not least because one of those descendants arrived in the White House. Michelle Obama is the great-granddaughter of a Pullman railroad porter, and, in 2015, Barack Obama designated the Pullman National Monument, in Chicago, to honor one of the country’s first planned company towns, a crucible of the labor and civil-rights movements. Pullman was one of twenty-nine monuments that President Obama protected through the Antiquities Act, more than any of his predecessors. Several of them focus on African-American history, including the Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad National Historical Park, in Maryland, and the Birmingham Civil Rights National Monument, the centerpiece of which is the A. G. Gaston Motel, a black-owned business where the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., stayed while planning the protests that helped spur the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

Politicians have long enjoyed cutting ribbons and giving speeches at the dedications of landmarks; even those who oppose funding the work of preservation know that saving endangered places can serve political ends. It’s not remarkable, then, that President Donald Trump has designated national monuments. But some of his selections have been surprising. His first, in October, 2018, was Camp Nelson, a Civil War site in Kentucky that is best known for what happened after the Union Army lifted its ban on African-American troops: ten thousand black men enlisted at the camp, and their family members, who technically remained enslaved, were given refugee status there. Last year, Trump made the home of the civil-rights activist Medgar Evers, in Mississippi, a national monument, too.

The President’s critics suggested that both designations were political favors: the first to Kentucky Republicans (Camp Nelson is the state’s first federal monument) and the second to Mississippi Republicans, including Evers’s older brother, Charles, who, in 2016, provided Trump with one of his more unexpected endorsements. But both sites had been under consideration for monument status for years. If anything, the designations might have been the Trump Administration’s political favor to itself—an attempt to redeem the White House after its inflammatory handling of the events in Charlottesville during the summer of 2017, when white supremacists gathered to protest, among other things, the removal of a statue of the Confederate general Robert E. Lee and one of them murdered a counter-protester named Heather Heyer.

Leggs speaks eloquently about the “powerful collision of culture, heritage, and public space” that produced the tragedy in Charlottesville, and about the way that it has simultaneously obscured and illuminated the work that he and his colleagues do. Since Charlottesville, the debate over Confederate monuments has garnered far more attention than questions about what other sites and histories deserve to be preserved. At the same time, that debate has only reinforced what Leggs has believed for decades: that preservation is political, and that the kinds of places and structures that we protect are less an indication of what we valued in the past than a matter of what we venerate today.

It was after Charlottesville that Leggs and his colleagues created the Action Fund, the largest-ever campaign to preserve African-American historic sites. In its first year alone, the Fund received more than eight hundred applications requesting nearly ninety-one million dollars in grants. Last year, the National Trust funded twenty-two recipients, including the oldest extant black church in the country, the African Meeting House in Boston; the house that Harriet Tubman bought from Senator William Seward in Auburn, New York, in 1858, and lived in for more than fifty years; and the Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, where, five years ago, nine members of the congregation were murdered by a white supremacist.

To support those and other efforts, Leggs has so far raised more than twenty million dollars for the Action Fund, from private individuals and nonprofits, including the Ford Foundation, the J.P.B. Foundation, and the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. Elizabeth Alexander, a poet and the Mellon Foundation’s president, told me that for a long time communities of color have had to “carry around knowledge and stories in our bodies,” because resources were not devoted to preserving the spaces that held those stories. She describes what Leggs and his colleagues do as “rescue work.”

Pursuing and maintaining relationships with donors like Mellon is essential to the success of the Action Fund, especially since the federal government stopped allocating funds to the National Trust in 1997. Leggs is gifted at that work, in part because he talks about historic sites with the kind of affection and enthusiasm that most people reserve for their children; given a single ceramic tile from a sanitarium or the boarded-up window of an abandoned motel, he can conjure a forgotten world with exuberant precision, converting entire audiences to his cause. But he is also persuasive because he understands the economics of historic preservation—not only how costly it can be but how profitable. Parks, monuments, and historic registers are not just designations; they are also funding directives. In a virtuous cycle, they can enable infrastructure improvements for beautification and safety, which promote tourism, which in turn promotes business development. Traditionally, however, the communities that benefit the most from historic preservation are the ones that need it the least. Critics of historic preservation often regard it primarily as a way for wealthy property owners to fend off development, including, all too frequently, affordable or high-density housing. In less affluent areas, designations are rare, and the same forces that are caustic for residents also corrode their history. At Weeksville, for instance, it took decades of penny drives and neighborhood bake sales to secure the sort of preservation that Colonial and Confederate sites often attain in a few years. Even then, the site’s status remained precarious: encroached on by development in the thirties, forties, and fifties, it was rescued in the sixties, only to have one of its protected homes burned down in the eighties and another vandalized in the early nineties. Only last spring, after the Weeksville Heritage Center launched a crowdfunding campaign to stave off closure, did New York City formally partner with the center, insuring increased financial support.

That kind of vulnerability is typical in marginalized communities, where few historic sites will ever sustain themselves with endowments or entry fees alone. As a result, part of the work of the Action Fund involves helping those communities identify “adaptive reuses” for historic spaces, a process that can lead to an afterlife that not many would recognize as preservation. Instead of turning sites into traditional museums, preservationists in communities of color have become more creative about what constitutes conservation.

The last surviving slave cottage in Richmond, which belonged to Emily Winfree, now sits next to the Devil’s Half Acre, in Shockoe Bottom. Photograph by Hannah Price for The New Yorker.

One of Leggs’s favorite examples is Villa Lewaro, in Irvington, New York, the estate of Madam C. J. Walker, a black hair-care entrepreneur and America’s first self-made female millionaire. The Trust convened African-American businesspeople, artists, and activists, who considered preservation ideas ranging from a spa and salon to an arts venue for concerts that would honor Walker’s support of artists like Vertner Woodson Tandy, the pioneering black architect who designed the spectacular thirty-four-room mansion. The Trust settled on a business angle, helping to arrange the sale of Villa Lewaro to Richelieu Dennis, the owner of Essence, who plans to make it the home of a hundred-million-dollar think tank supporting black female entrepreneurs. “It’s about economic development,” Leggs told me. “It’s about the empowerment of people as much as it’s about the history.”

That kind of empowerment does not come just from preserving new sites; Leggs and his colleagues also advocate for the reinterpretation of old ones. Twenty years ago, Representative Jesse Jackson, Jr., dropped into an appropriations bill three paragraphs encouraging the National Park Service to acknowledge “in all of their public displays and multimedia educational presentations the unique role that the institution of slavery played in causing the Civil War.” That legislative maneuver helped bring about a sweeping interpretive correction to this country’s heritage tourism, and ultimately led to new exhibits around the U.S., including the Best Farm Slave Village, at the Monocacy National Battlefield.

“A lot of our work is to balance America’s collective memory,” Leggs said. But that work can’t be accomplished without rebalancing something else. To diversify historic preservation, you need to address not just what is preserved but who is preserving it—because, as it turns out, what counts as history has a lot to do with who is doing the counting.

Leggs told me that he has long felt like “one of one” in his field, and for good reason. African-Americans constitute less than six per cent of the more than twenty thousand employees of the National Park Service, and they are underrepresented in most other careers related to historic preservation, accounting for not quite four per cent of academic archeologists, five per cent of licensed architects and engineers, and less than one per cent of professional preservationists.

Leggs came to the field by chance. He grew up in Paducah, Kentucky, a small city on the Ohio River, where he watched his church raise funds to repair its roof, and attended annual family reunions that always found their way to cemeteries, where they cleaned, mowed the grass, and landscaped the graves. After studying marketing at the University of Kentucky, he received a master’s degree at the business school there. Leggs has a twin brother, who went to work at a now defunct uranium-enrichment plant in Paducah; his younger sister stayed in the area, too. Leggs had been so focussed on getting his degrees that he didn’t know what to do with them after graduation. He was interested in design, and thought about taking a furniture-making class at the University of Kentucky’s School of Architecture, but when he went to enroll a dean recruited him for the graduate program in historic preservation, partly by telling him that he could be the program’s first black graduate. “I had no idea about architectural history, no formal understanding of preservation, but it felt right,” Leggs said.

His first field assignment was to inventory Rosenwald schools. Devised by Booker T. Washington and funded by the philanthropist Julius Rosenwald, the schools served black children during the era of segregated education. Almost five thousand of them were built in fifteen Southern states between 1912 and 1932, and they educated more than six hundred thousand students, including some of the very civil-rights leaders who later helped to make them obsolete. In the years after Brown v. Board of Education, while the schoolhouses that had served rural whites were romanticized and preserved, ninety per cent of the Rosenwald schools were demolished or allowed to fall into disrepair.

Leggs’s task was to find and document those that remained in Kentucky. While walking through them, “I had this multisensory experience,” he recalled. “I could see, touch, smell, hear the creaking floorboards when I stepped inside.” That strange feeling made sense, Leggs said, when he learned, later, that his parents had both attended Rosenwald schools. His mother had died when he was a teen-ager, but the school visits prompted conversations with his father about the family’s history, convincing Leggs of the power that physical places have in shaping cultural memory.

As a graduate student, Leggs received one of the National Trust’s Mildred Colodny diversity scholarships, and since then he has concentrated on bringing new people into his field. Doing so involves credentialling new colleagues, and also convincing community organizers, artists, real-estate developers, and other professionals that they are already doing the work of preservation. “I think part of what we want to do is to reconstruct the identity of traditional preservationists,” Leggs told me. As an assistant clinical professor at the University of Maryland School of Architecture, Planning, and Preservation, Leggs sometimes interacts with students who have never met a preservationist of color, or whose portfolios would never have included sites of African-American history if not for his encouragement. He also meets regularly with students who are taking part in the Action Fund’s campus events or preservation fieldwork.

Last fall, Leggs met with Monique Robinson, an undergraduate at Morgan State University, in Baltimore—one of a hundred and four operating historically black colleges and universities around the country, and one of several where the National Trust is working to promote historic preservation, in part by protecting buildings on campus, including some designed by pioneering black architects like Leon Bridges and Albert Cassell. Robinson, a senior who came to Morgan to study architecture, had learned about preservation through a National Trust course. “I always thought I would just go join a firm and work my way up,” she said. “But then I met Brent, and I saw how preservation can look at what was there before and understand what’s important to a community.”

Robinson and Leggs stood talking in the long, light-filled atrium of the school’s Center for the Built Environment and Infrastructure Studies. Leggs had to leave that afternoon to catch a train to New York, for a meeting at the Langston Hughes House, in Harlem; Robinson was preparing for exams and finishing grad-school applications. But they got to talking about Old Jenkins, a building at Morgan State that was slated for demolition. To its detractors, the building, a brutalist behavioral-science headquarters, looks like a fortress that swallowed a ziggurat. Worse, its blocky façade obstructs the view from Carnegie Hall, one of the most distinguished buildings on campus. “Oh, Jenkins,” Robinson said, smiling as if she’d been asked about her first crush. “I really just love it.”

Leggs, who feels the same, tried to convert me to the cause. During a tour, he pointed out how Jenkins reflects not only the global history of design but the history of Morgan State. Named for one of the university’s former presidents, the building was designed by Louis Edwin Fry, Sr., the first African-American to receive a master’s degree in architecture from Harvard. Its hidden amphitheatre has seen forty-five years of lectures, homecomings, and commencements. Yet any effort to preserve Jenkins would face serious difficulties: decades of deferred maintenance have made it extraordinarily costly to restore. And, even setting aside the question of money, it suffers from a problem that often haunts historic preservation—to the general public, some important places just seem too ugly, insignificant, or inconvenient to keep around.

Take the Hill, a historically black neighborhood in the town of Easton, on Maryland’s Eastern Shore, that is the site of a preservation project that even a decade ago might have been met with confusion. It is not immediately obvious why this area of several blocks is historically significant, but the collection of black churches, black businesses, and dozens of single-family homes is thought by some archeologists to be the oldest continuously occupied free-black community in the country—perhaps two decades older than Treme. With the backing of the National Trust, academics at Morgan State have led an effort to research and reconstruct the Hill, unearthing the stories of early residents, like Grace Brooks, a midwife who freed herself and her family in 1788 and became one of the first black homeowners in town, and Joseph Chain, a black businessman who opened his own barbershop and grocery store after his arrival in 1810. The Hill also sheds new light on the story of Frederick Douglass, who watched those lives unfold in freedom while he was enslaved in the same county and imprisoned in the same town.

For Leggs, the Hill offers a compelling demonstration of all that historic preservation can accomplish in communities of color. In keeping with the early history of homeownership there, organizers and local officials are using tax breaks and development funds to help renters become homeowners, hoping to forestall developer-led gentrification and insure that the neighborhood will continue to be occupied by descendants of the original free blacks who settled it. At the same time, Morgan State is addressing the pipeline problem in the field of preservation by recruiting college students and young people from the neighborhood for research, analysis, and archeological digs.

The town of Easton has embraced the Hill, supporting not only the effort to document its history but also initiatives to retain minority families. Historical maps are available online and in the county tourism office, and local schoolchildren now go on field trips to see a historically black community that dates back to the Revolutionary War era, following a walking tour that brings to life what they might not otherwise have been taught, in situ or at all.

Not all sites move from the margins to the mainstream so smoothly. At Shockoe Bottom, the Defenders are still fighting to commemorate the legacy of Gabriel’s rebellion and the memory of all the other African-Americans who were sold and buried there. Economic development and historic preservation seem at odds, and even many community stakeholders who agree about the importance of the site disagree about how best to memorialize it. After the Trust included Shockoe Bottom on its most-endangered-places list, the city proposed preserving a single small area, the so-called Devil’s Half Acre, on which the slave trader Robert Lumpkin ran a jail. The Defenders are advocating for a nine-acre memorial park centered on the burial ground. They point to an economic study commissioned by the Trust, which found that an $8.7-million investment in that park would generate $11.5 million in jobs.

Ana Edwards, an artist and a historian, moved to Richmond in the late eighties and learned that two of her ancestors had been sold out of the city. She has co-chaired the Sacred Ground Project with her husband for the last fifteen years, some of those while working on a master’s degree in history. Her research focusses on the life of a free black man accused but ultimately exonerated of participating in Gabriel’s rebellion. Edwards believes that Shockoe Bottom should be a site of reflection and remembrance but also of resistance, offering visitors an alternative to the history that Richmond has long revered. Four of this country’s more than seventeen hundred public memorials to the Confederacy stand not far from Shockoe Bottom, on Monument Avenue—statues of Jefferson Davis, Robert E. Lee, Thomas (Stonewall) Jackson, and J. E. B. Stuart. As in Charlottesville, white supremacists have rallied to protect those Confederate monuments, a reminder of how necessary African-American historic preservation is. “I don’t know if this space can do all the work our society needs it to,” Edwards told me one night, while walking through Shockoe Bottom, shouting to be heard over the sound of eighteen-wheelers passing on the interstate overhead. “But we need this place.”

Mayor Levar Stoney, who was elected in 2016, agrees that Shockoe Bottom is an important site for the city and for the country. “Our history in Richmond is good, bad, and ugly,” he told me. “And I think we owe it to our ancestors and the descendants of these slaves to tell the complete story, no matter how bad or ugly it might have been.” More than a year ago, his administration established a working group called the Shockoe Alliance, which includes people from the Sacred Ground Project, the Slave Trail Commission, and Preservation Virginia, and also from the Shockoe Neighborhood Association and the Shockoe Business Association. To date, they have reached no agreement on Shockoe Bottom’s future. But Leggs, who has the patience of someone who spends his time thinking in centuries, is optimistic that, through the Shockoe Alliance, the city will agree on an appropriate plan for the site. He knows that the arc of history is long and unpredictable, and he is used to doing his work one donation and one student at a time. He has seen that patience rewarded with more recognized sites and with the involvement of more people who have the knowledge and commitment to save them. He has also seen how slowly a project can unfold. His career began nearly two decades ago with the Rosenwald schools, and now he is involved in an effort to create a discontinuous national park that could include Rosenwald’s childhood home, in Springfield; the corporate headquarters of Sears, Roebuck and Company, in Chicago; and a number of the schools throughout the South.

Yet Leggs also knows that some stories are more widely cherished than others. The interracial and interfaith friendship between Julius Rosenwald and Booker T. Washington; the entrepreneurism of Madam C. J. Walker and A. G. Gaston; the audacity and courage of the self-emancipated Frederick Douglass—it is comparatively easy to rally public support for preserving these inspiring legacies. It is a very different matter to persuade a municipality to memorialize its deep economic dependence on slavery. Shockoe Bottom is not just a more expensive place to preserve financially; it’s more expensive emotionally and morally as well. “It should be a site of conscience,” Leggs said. “A place where the truth is told, and visitors reflect, and where reconciliation can happen.” Even if Leggs and the National Trust succeed in helping the Defenders for Freedom realize their vision in Richmond, as they have with so many other grassroots organizations in so many other cities and towns around the country, all they can do is preserve the past. The future is up to the rest of us.

This article was originally published by The New Yorker.